When the National Park Service (NPS) was created on August 25, 1916, its mission was to “preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” Today, the NPS is tasked with the ongoing challenge of preserving ecologically and historically important sites—while making sure that they remain accessible to the general public.

The definition of whether or not a place is “accessible” may vary widely from one person to another, and with so many different monuments and landscapes spread across the U.S., there is no magic formula—like building a ramp or installing a handrail—for providing accessibility across the board.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were nearly 40 million Americans living with a disability in 2015, and the National Park Service conservatively estimates that a minimum of 28 million visitors with disabilities from all over the world visit national parks annually. Making sure that everyone truly has access to all 419 NPS sites is an ongoing battle fought daily by activists, outdoors organizations, and the Park Service itself.

While the NPS has been in compliance with the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), it wasn’t until 2012 that the NPS formed its own Accessibility Task Force.

Beyond the parking lot

The mission of the Accessibility Task Force is to ensure “that all members of our visiting public are afforded access to our significant sites and the stories within.” The five-year plan, which began in 2015, promises to address the lack of accessible restrooms, entrances, parking lots, and water fountains in many park visitor centers, and to remove additional accessibility challenges at trails, campgrounds, and beaches in national parks.

“You can research ‘accessibility’ all you want, but the information found never truly describes what accessibility is,” says Matthew Tilford, a medical supplies representative for Apple West Home Medical Supply. “There are so many forms of disability and everyone has different abilities.”

Tilford, who describes himself as an adventurer at heart, uses a wheelchair. The most common issues he sees in his travels are too-small bathrooms and sidewalks without proper curb cuts.

“Accessibility issues continue well beyond the parking lot,” says Adrienne Ritchie, director of marketing at GRIT Freedom Chair. “We’ve heard and seen many examples where a ramp is present, which is great, but it leads to a place that isn’t accessible. Similarly, in places where accessible parking is available, these spots may end up being far away from amenities making travel much more difficult.”

Most national and state parks usually offer at least one accessible campsite and restroom, but doors are often too narrow to fit a wheelchair. Historical sites concerned with keeping bicycles and motorized vehicles off pathways may also be unintentionally alienating visitors who use mobility aids.

Nerissa Cannon, who describes herself as an “adaptive adventurer,” skis, hikes, rock climbs, kayaks, and camps while using a wheelchair. “I’m always willing to crawl up some steps in order to do something I want to do, but having something too narrow to fit my wheelchair through at all can be frustrating,” she says.

Positive strides

In Yellowstone National Park, accessibility improvements have included a renovated visitor center in addition to “enhanced access at restrooms, walkways, trails, and overlooks. Accessible picnic tables and fire rings have been installed at many campgrounds and picnic areas—construction of accessible boardwalks to popular hydrothermal features is on-going,” says Linda Veress, public information specialist at the park.

But making a handful of trails accessible is only the beginning—just because more people can visit a particular site doesn’t mean that people want to: “We think it’s awesome that there are more and more wheelchair-accessible trails popping up, but we’ve heard from our riders that sometimes these trails are a little boring,” says Ritchie. “Just because a trail is accessible doesn’t mean it has to be lackluster.”

“I want to experience more than a mile of nature.”

“I may use a wheelchair but I’m extremely active,” says Tilford. “I downhill mountain bike, road bike, water ski, snow ski, and hike. Most parks’ disabled-dedicated paths are only a few miles. I appreciate the offer but I want more. I want to experience more than a mile of nature.”

At Grand Canyon National Park, all park shuttle buses are wheelchair accessible, but most motorized scooters still won’t fit. Visitors with mobility limitations may receive access to some areas normally closed to traffic by obtaining a Scenic Drive Accessibility Permit at one of the park’s visitor centers. Service animals are allowed on trails as long as they’re leashed, and ASL interpreters can be requested a few days in advance of your visit.

“I’m a big advocate for keeping things in their purest form,” says Cannon. “Meaning, I’m not expecting them to pave and grade the wilderness to make it wheelchair accessible. However, often the barrier is a barrier to technology. There are a lot of instances where a trail would be ‘accessible’ to a visitor with a mobility limitation simply by using the right equipment.”

“It’s not only acknowledging that this community exists, but it’s giving them the means to get outside and fulfill their desire for adventure.”

Recently, Staunton State Park became the first Colorado state park to purchase two all-terrain wheelchairs for visitors to use while hiking. “This is amazing because it’s not only acknowledging that this community exists, but it’s giving them the means to get outside and fulfill their desire for adventure,” says Ritchie.

An economic benefit

Although cold, hard cash isn’t the most empathetic argument for improving accessibility, there is data to support economic benefits—not just in national parks, but in the travel industry as a whole. The NPS Accessibility Task Force determined that “lack of access for visitors with disabilities could result in $3.6 billion annually in lost revenue to parks, partners, concessioners, and gateway communities.”

“Like many people with disabilities, we spend a lot of money traveling, but if a business isn’t accessible to us we can’t frequent your establishment,” says Tilford. “The Americans with Disabilities Act is 30 years old. It’s time to start following the law. This is beneficial to both people with disabilities and our economy.”

Accessibility information for individual parks can be found on the respective park’s website under the “Plan Your Visit” tab. U.S. citizens and permanent residents with disabilities can also apply for a free lifetime Access pass—which includes access to 2,000 federal recreation sites—in person or through the mail.

“Don’t be afraid to venture somewhere that you might not expect to be accessible,” says Cannon. “My favorite types of trips to take are road trips. I love taking the back roads through the small towns, and eating at the dive restaurants, then finding a nice camping spot on public land. Getting away from the tourists and understanding the local culture of where I’m passing through is where I feel enriched the most.”

Beyond mobility challenges

The National Ability Center (NAC) works with the National Park Service to get more people outside by helping to identify and remove possible barriers to entry. Their Splore Outdoor Adventure arm has been leading river trips for people of all abilities since before the ADA. Using specialized adaptive equipment and trained staff and volunteers, the NAC is working toward representation of people of all abilities in the outdoor industry.

“When it comes to national parks and public lands, we are often dealing with wild lands—which can mean unpaved roads, steep grades, and other barriers to access,” says Nathan Vink, the National Ability Center’s Adventure Program senior manager. “There are a lot of introductory clinics to learn how to camp, climb, or mountain bike. But there are not yet many comparable opportunities for those with different abilities.”

The Accessibility Task Force also encourages parks to look beyond mobility challenges and to address issues faced by those with sensory and other less visible impairments. The NPS has created a diversity and inclusion department to make sure that brochures, audio elements, and websites are accessible, and to train staff and volunteers to better assist all visitors.

“I would like to see more rangers understanding trail obstacles and conditions and how they might affect a visitor,” says Cannon. “I am happy to go explore on my own and figure things out, but I know a lot of visitors could benefit from more detailed explanations of trails so they can make a decision as to whether or not they can attempt it.”

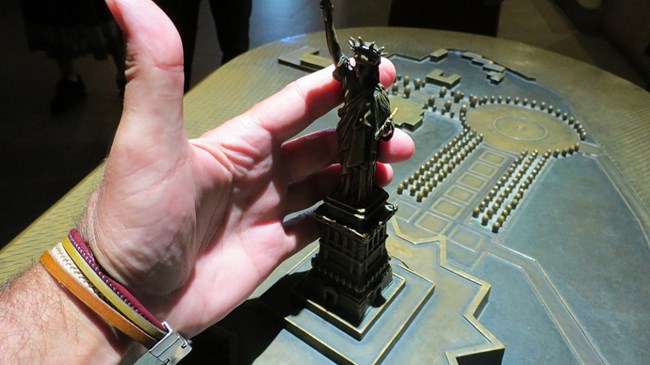

At many parks, brochures are available in a variety of different languages, audio described, text-only, and braille. At the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, audio descriptive tours created specifically for the blind and visually impaired are available free of charge, and several tactile displays are located inside of the monument.

“Don’t make an assumption of someone’s abilities just by looking at them,” says Ritchie. “Sure, it may take a bit more work and could be a bit more risky, but many people want to get off the pavement and feel a sense of adventure. The diversity of people who want to get outside is growing and growing—don’t count anyone out. The outdoors is for everyone.”

“The diversity of people who want to get outside is growing and growing—don’t count anyone out. The outdoors is for everyone.”

The National Ability Center also helps educate people with disabilities who are interested in travel, and they offer their own whitewater rafting adventures, adaptive mountain bike trips, and national park tours. “The ultimate goal is to see each individual have the ability to recreate and enjoy the great outdoors on their own or with family and friends,” says Vink.

“Don’t let your own mind stop you from seeing the sun rise on El Capitan in California’s Yosemite National Park, the prairie dogs standing tall outside their burrows in South Dakota’s Badlands National Park, or the beautiful spring flowers in California’s Joshua Tree National Park,” says Tilford. “It’s not impossible to travel while being disabled. It may take extra effort but it’s always worth it.”