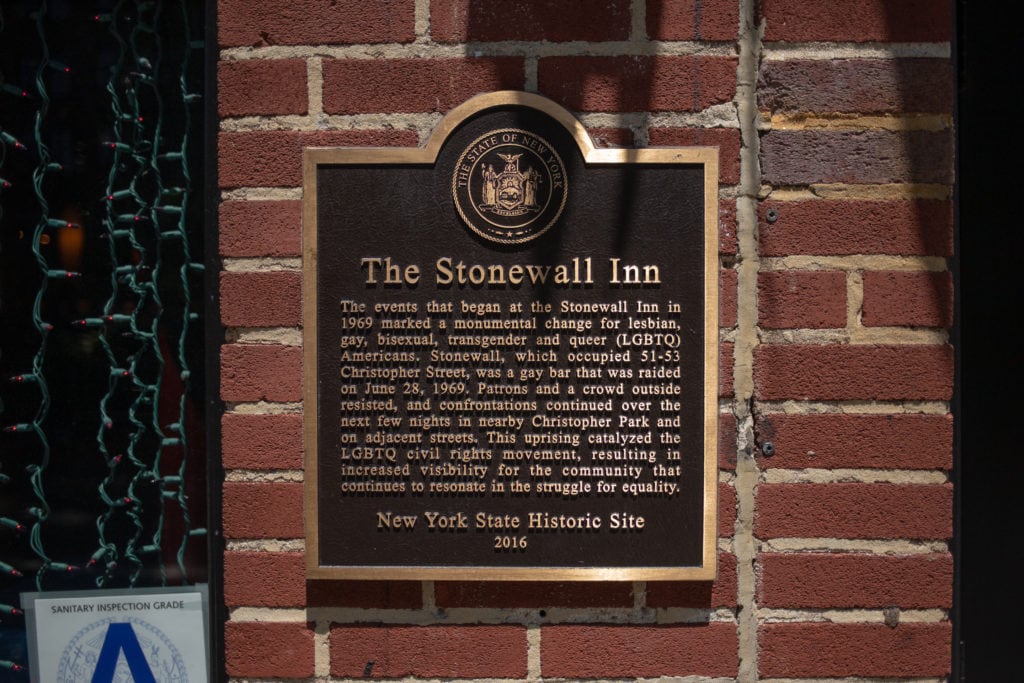

Bars are generally hot, loud, and crowded; an assault on every one of my—admittedly delicate—senses. The Stonewall Inn is all of these things but it’s also so much more: The bar is located in a landmarked, 19th-century stable in the Greenwich Village historic district; it’s considered to be the birthplace of the modern LGBTQ rights movement; and in 2016, the park directly across the street from the Stonewall became the first LGBTQ historic site to be designated as a national monument.

I first visit the Stonewall Inn in early June, 2019, at the beginning of Pride month—more than 20 years after I first realized that I felt different than my peers. While my friends were busy idolizing Leonardo DiCaprio and other ‘90s heartthrobs, I grew increasingly terrified about not only the absence of similar feelings in my life, but also by the realization that whenever I envisioned my future life, I always saw myself with a woman.

New York City is the host of this year’s World Pride celebration, and on a Friday night the Stonewall is packed. I’m on a date and it’s going well. As I make my way through the tight crowd to the bar, I immediately notice the patrons here are especially kind and courteous—there’s no aggressive pushing, just a polite rearrangement of bodies, backed by a chorus of I’m sorrys and No, after yous. A complete stranger walks toward me, places his hand softly on my shoulder, and screams, “You’re gorgeous!”

We find two stools and sit down, but we’re soon told—very politely—to move for the impending drag show. The bar is loud and increasingly stuffy, but the performer is luminous and her beautiful voice cuts through the chatter with a selection of ‘90s hits.

While the crowd joyfully waves dollar bills, I catch a glimpse of an older man and woman reading a plaque by the entrance that details the Stonewall’s historical significance. They take a selfie in front of the neon “Stonewall Inn” sign and send it off into the ether. I wish that I too could snap a photo of this moment and send it back to my 13-year-old self, a time-traveling note of hope for a future filled with the acceptance, joy, and love I feared I’d never find. A note that simply says: You will be OK.

The birthplace of a movement

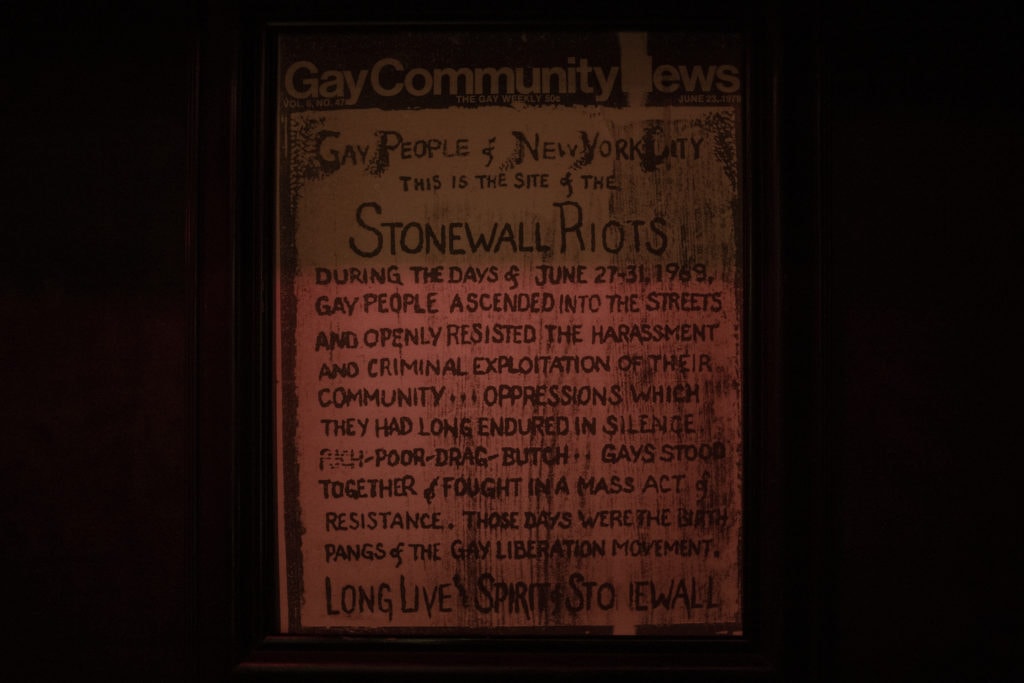

At 1:20 a.m. on June 28, 1969, eight police officers raided the Stonewall Inn, which, at the time, was the largest gay establishment in the U.S. Police raids were common in places that catered to the gay community. “It was just random,” Martin Boyce, a Stonewall riot participant, says in the documentary Stonewall Forever. “It was whoever’s face they didn’t like. There was this kind of rite of humiliation, they would have to fully humiliate you before they could let you go.”

What came next, however, was not common: 200 patrons inside the bar that night did not cooperate with the raid, and instead decided that they would fight back. The crowd outside on Christopher Street quickly swelled to nearly 600. Pennies, bottles, and bricks were thrown. Ten police officers barricaded themselves inside of the Stonewall. By 4 a.m., the streets were cleared, everything in the Stonewall had been destroyed, and a movement was born.

“There was no leaders, nothing was planned,” says Boyce. “But everything went amazingly in our favor.”

Over the next few days, thousands of people descended upon the area surrounding the Stonewall and the “rebellion paved the way for future members of the community to not accept treatment as second-class citizens but rather to expect that the LGBTQ community be treated as equals in the eyes of both the government and society at large,” according to the Stonewall Inn’s website.

Two weeks later, the Gay Liberation Front began organizing. The first-ever Pride parade—then called the Christopher Street Liberation Day March—took place on June 28, 1970, the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Marchers arranged themselves in a single file line to stretch the parade, but as they marched north toward Central Park, more and more people began to join.

“What began as a question mark downtown, ended in an exclamation point,” says Boyce.

More than just a bar

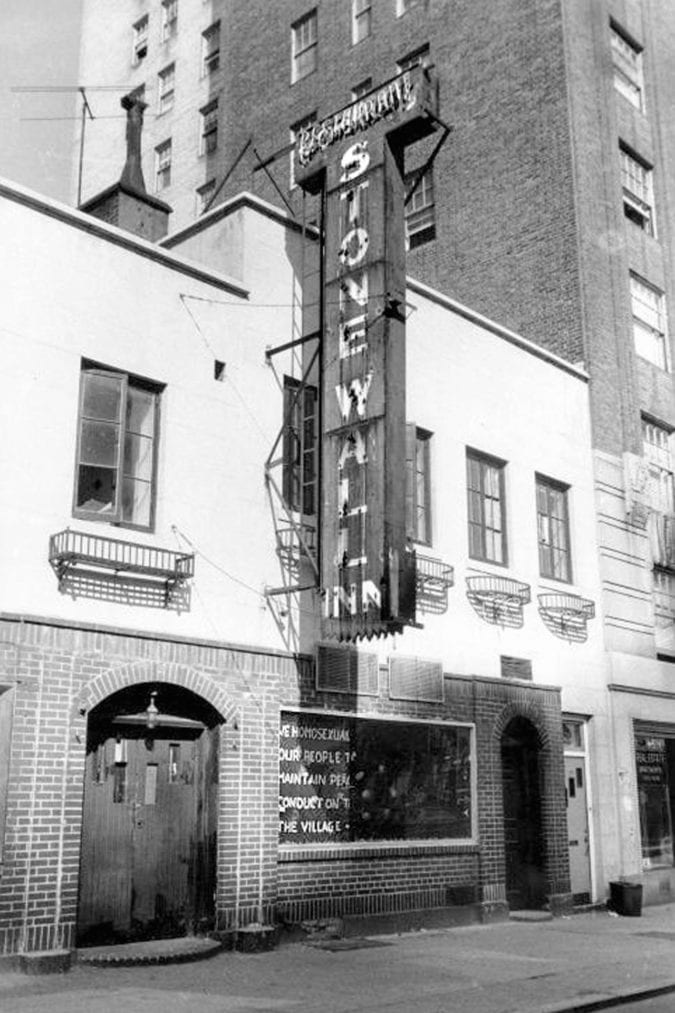

The Stonewall Inn wasn’t always hallowed ground for the queer community. In 1934, Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn opened in its current location, operating as both a restaurant and bar. In 1964, the interior was destroyed by a fire, and in 1966, the space became a gay bar.

“The interior of the bar was horrific. I mean, they didn’t have running water,” Boyce says. “So—if you knew—no one ordered a drink in a glass. But it was ours, so who cared what it looked like.”

Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan The walls of the bar are filled with historic photos and news clippings. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Brooklyn Brewery created the Stonewall Inn IPA to celebrate World Pride. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The shift from restaurant to gay bar was a popular one almost immediately because of the Stonewall’s unique policy allowing same sex couples to dance with one another. “It was always crowded, you know. Always crowded,” Jay Toole says in Stonewall Forever. “Walking into the bar and seeing so many of us, it was like home.”

The Stonewall quickly became the central spoke in the West Village, a neighborhood already known as a haven for the gay community. “I said, ‘Oh wow, this is heaven. There’s other people like me,’” transgender pioneer and activist Judy Bowen says in Stonewall Forever. “Tourists would come down in their double-decker buses taking pictures because we were all dressed outrageously. I started to grow here because I was free.”

The Stonewall’s significance in the LGBTQ community wasn’t enough to keep it open in the years following the riots. “Almost everything in the Stonewall Inn was broken,” according to the bar’s website. “Pay phones, toilets, mirrors, jukeboxes, and cigarette machines were all smashed, possibly in the riot and possibly by the police.”

Over the years the space has been host to a bagel sandwich shop, a Chinese restaurant, and a shoe store; in the early 1990s it became a gay bar once again, but it closed in 2006 due in part to mismanagement and noise complaints from neighbors. The bar reopened in 2007 under new management and currently hosts drag shows, trivia nights, karaoke, bingo, private parties, and fundraisers.

Two steps forward, one step back

Although almost nothing about the current iteration of the Stonewall Inn is original, if structures could talk, this one would have a lot to say. In 2019 in particular, generations of activists and members of the LGBTQ community are gathering to remember the riots and reflect on how much has changed—or hasn’t changed—in the 50 years since the first brick was thrown on Christopher Street.

Almost exactly 46 years after the riots, on June 26, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all state bans on same-sex marriage. A crowd once again gathered outside of the Stonewall, but this time the mood was celebratory.

While there have undeniably been huge wins for the queer community, there have also been frustrating setbacks and differing opinions about what the fight is really about. From the very beginning, transgender and gender non-conforming people felt excluded from a movement that was lead by two transgender activists, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera.

In 2017, the Pride flag—a LGBTQ symbol since 1978—got an update in Philadelphia to include a black and brown stripe as a nod to the additional challenges faced by queer people of color. Last year, an alternate design included the colors from the transgender flag as well.

“When we say ‘equality,’ equality has to be for everybody,” Bowen says.

Stonewall Forever

My first experience at Stonewall is such a positive one that I return a few weeks later, on a sunny Sunday afternoon. The tiny triangular park across from the bar is packed with people and one man is playing a flute, while another plays a piano plastered with rainbow stickers. They pay no attention to one another and their unintentional duet is somehow both discordant and harmonious—punctuated by the sound of dozens of rainbow flags flapping furiously in the breeze.

The Christopher Park and surrounding block was designated a national monument in 2016. Photo: Alexandra Charitan Statues inside of Christopher Park. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A park ranger replaces pride flags at the national monument site. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The rainbow flags are zip-tied to the perimeter fence by the site’s lone park ranger, and replenished daily as needed. The 7.7-acre national monument, which comprises Christopher Park and the block of Christopher Street bordering the park, was designated in 2016 by President Obama. Unlike other national monuments, there is no visitor center and no formal talks or tours. The current mission of the Parks Department’s presence is simply to preserve the story and the resource; visitors can pick up an informational brochure or engage via the new interactive website and AR app, Stonewall Forever.

Places of significance are also a direct line of communication to the future, a way of saying “we were here and what we did mattered.”

According to the NPS brochure, national monuments “reflect the American experience through natural wonders, sites of celebration, conscience, and civil rights.” Humans are territorial creatures, habitually marking spaces for the perceived significance of emotional events that take place within their walls. Experiences are ephemeral and memories so intangible that we worship objects and structures, grasping any physical connection to our past. Places of significance are also a direct line of communication to the future, a way of saying “we were here and what we did mattered.”

A near-constant stream of people cross the street to stand in front of the Stonewall Inn, taking selfies, and wrapping themselves in oversized Pride flags. They smile because that’s what you do for photos, but I suspect it’s more than that—they’re smiling because they’ve made a pilgrimage to the Stonewall, as I did. I’m embarrassed that I lived in New York City for nearly six years before I visited the historic bar, but I also know that recognizing and embracing my identity was something I had to do at my own pace.

No matter how far visitors may have traveled, or how long it took them to get to Christopher Street, they stand on the shoulders of the pioneers who risked everything to demand that LGBTQ people be recognized as just that: people. People who deserve respect, equality, and a chance to love and be loved.

If you go

Due to the spread of COVID-19, many points of interest are currently closed. Please call ahead to any location you plan to visit to make sure they are open.