Sailors passing through Gardiners Bay into the Peconic River near the North Fork of Long Island may have thought they were hallucinating when a three-story, white shiplap structure officially known as the Long Beach Bar Lighthouse came into view. Lighthouses are traditionally more light than house, but the Long Beach Bar Lighthouse—with a light tower rising from the middle of a mansard roof-topped cottage—is equal parts both.

The lighthouse, one of approximately 25 that still dot the shores of Long Island, was constructed in 1871. It originally sat on piles screwed into the river bottom; this construction method, known as screwpile, is more common in warmer, southern waters where winter ice is not a concern. Because the lighthouse—perched on criss-crossing, spindly legs—resembled a water bug from afar, it became known as “Bug Light.”

Just one year after the lighthouse was completed for $17,000, a stone foundation made of riprap was added at an additional cost of $20,000 (nearly $400,000 today) to help protect against the harsh Northeast winters. A concrete foundation replaced the piles entirely in 1926, but the nickname stuck.

When I take a dedicated lighthouse cruise from Greenport, New York, on the last day of August, I know what to expect. And yet, I’m still dazzled as the lighthouse comes into view—it seems almost too picture-perfect to be true; no longer resembling a bug, it’s as if a motel painting or Christmas ornament has suddenly come to life.

A family tradition

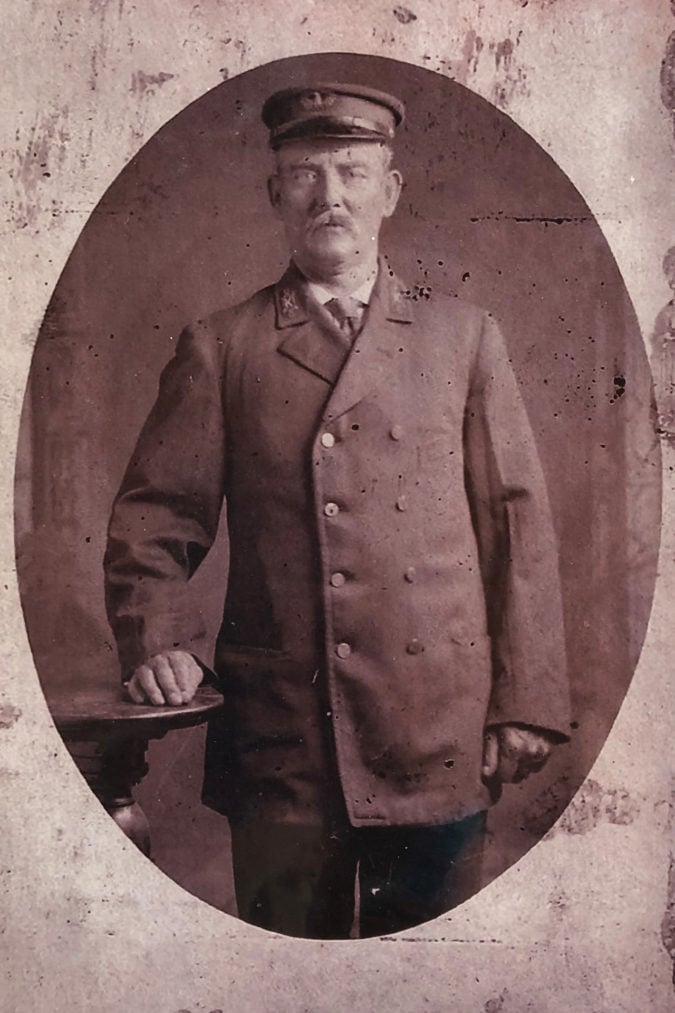

Our tour guide for the evening is Bob Allen, the great-grandson of William H. Follett, a lighthouse keeper from 1912 until 1940. Over the course of his career, Follett was stationed at lighthouses on Montauk Point and Cedar Island before moving to Bug Light in the 1930s. Allen’s father quit school in the seventh grade to help his grandfather at the lighthouse full time, and he remained at Bug Light until it was taken out of commission in 1948.

In 1955, the lighthouse was put up for auction and purchased by the Orient Point Marine Historical Association for $1,710. On July 4, 1963, the lighthouse was completely destroyed by a fire set by a group of “punk kids,” according to Allen. A fundraising campaign launched by Greenport’s East End Seaport Museum raised $140,000 for the construction of a working replica of the lighthouse. The structure was rebuilt on land by Greenport Yacht and Shipbuilding, floated in sections on two barges, and reconstructed on the original foundation in 1990.

Over the years, the lighthouse was powered by whale oil, lard, kerosene, and oil vapor. Bug Light never had electricity, but its current 10-inch, solar-powered light is maintained by the United States Coast Guard. Electricity, automation, and other technological advances have made 24/7 lighthouse keepers virtually obsolete, but Allen continues his family’s tradition by giving tours in conjunction with the museum. “I have to be careful when I say the name fast,” says Allen. “Just to clarify, Bud Light does not own this lighthouse.”

Passing time

Allen’s great-grandfather lived year round in Bug Light with his wife and grandchild. Allen peppers his lighthouse facts in between family anecdotes and archival photographs. “People ask me, ‘When does the keeper get a chance to leave the lighthouse?’” he says. “The answer is, ‘You don’t.’” On the rare occasions when Follett would go into town, “great-grandma took over,” Allen says.

Instead of running water, the Folletts gathered rainwater in a cistern and dried laundry on a clothesline. To accommodate tours, dividing walls were not added in the reconstruction, but the main floor once included a kitchen, a sitting room, and a living room; the upstairs had three bedrooms and several closets.

Lighthouses were invaluable navigation tools for boats in an era before reliable electronic navigation systems. Their bright lights mark dangerous coastlines and alert sailors to hazardous conditions. When fog impacted visibility, Allen’s father had to wind the fog bell every two hours; the clapper would strike the bell every 15 seconds. “I asked my father, ‘Isn’t that annoying to hear so often?’ and he replied, ‘No, the thing we worried about was not hearing the bell because it meant that ships might be in danger.’”

Before Follett came to Bug Light, a previous keeper had a few drinks and fell asleep on a clear summer night in 1911. “What did lighthouse keepers do to pass the time?” Allen asks. “The answer is, they drank.” The night quickly turned foggy, and a 247-foot passenger ship ran aground at the base of the lighthouse.

Although the isolation and constant vigilance required of a lighthouse keeper may seem like a prison sentence to some people, Allen thinks his great-grandfather and father could have chosen a worse career: “You don’t have to mow the lawn or wash the bricks,” says Allen. “There are no neighbors out here to bother you.”

Storms and spirits

Lighthouses were erected to help prevent maritime accidents, but they’re often just as vulnerable as the ships they’re designed to protect. On September 22, 1938, a massive hurricane moved up the East Coast, creating waves more than 50 feet tall. Two of the lighthouse’s second-story windows were broken and the light was extinguished. Allen says his dad, who rode out the storm, reported that the noise was deafening: “Like having a steam locomotive in the living room.” In 2012, Superstorm Sandy wiped out the lighthouse’s dock and flooded the first floor.

Sailboats by the lighthouse. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The lighthouse’s guard dog, Patch. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A lifesaver on the boat. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The foundation was added to the lighthouse in 1926. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The inside of Bug Lighthouse. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Riprap stones around the lighthouse. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The view of Greenport, Long Island from the bay. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Although the full-time keepers are long gone, “We actually do have someone who stays here 24/7,” Allen says as he points to a full-size skeleton dressed as a pirate leaning in the corner. Patch, a skeleton guard dog with an eye patch taped over his right eye, sits silently at his feet.

“I had a bottle of wine in case my great-grandfather didn’t come—and a bottle of vodka in case he did. They were looking for spirits and I already had mine.”

In 2012, Allen was approached by a paranormal society. They wanted to do an investigation of the lighthouse and asked Allen to help summon his departed ancestors. Since so little of the original lighthouse remains, Allen was skeptical and maybe even a bit nervous—“Suppose I don’t want to be visited?” he asked—but his daughter convinced him to participate.

“I had a bottle of wine in case my great-grandfather didn’t come—and a bottle of vodka in case he did,” Allen says, laughing. “They were looking for spirits and I already had mine.”

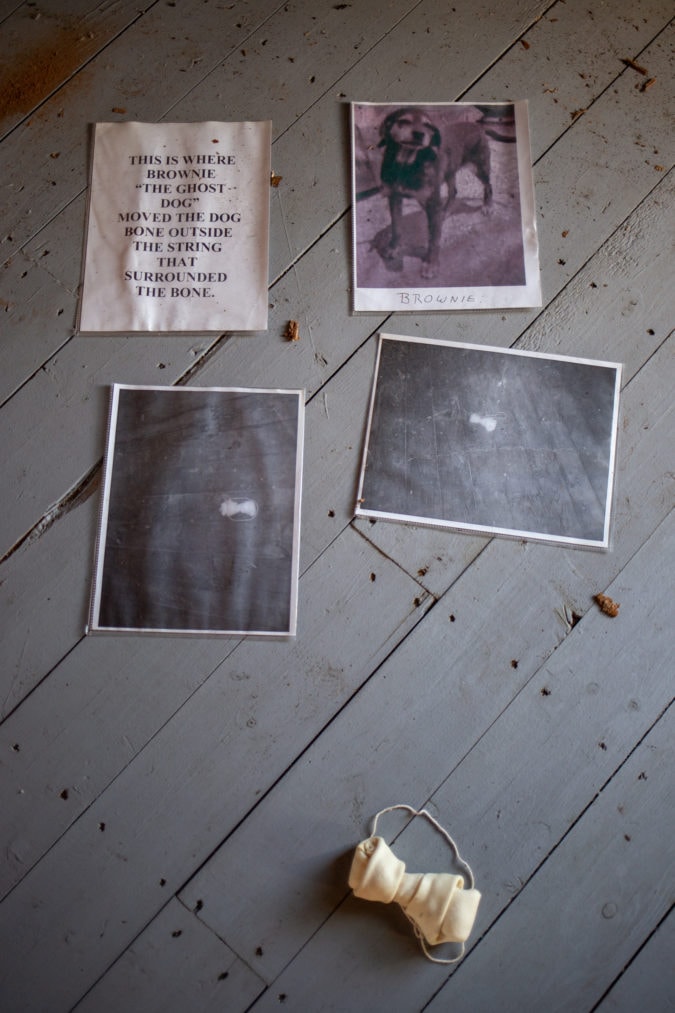

Follett never made an appearance, but the investigators didn’t leave empty-handed. Hoping to conjure Follett’s dog Brownie, a bone was left upstairs inside of a circle of string. After a few hours, the bone had moved—seemingly on its own—outside of the string. Before-and-after photographs currently on display show the bone’s alleged path.

Even after witnessing this phenomenon, Allen is still skeptical. “I’m not trying to get you to believe in a ghost dog,” he says. But he’s also not ready to concede that the lighthouse is entirely free of spirits. “Brownie died in 1940 and we did the investigation in 2012—after 72 years, if any dog deserved a bone, Brownie did.”

If you go

Tours of Bug Light are offered on Wednesdays and Saturdays through October 19.