On April 1, the cherry blossoms in Washington D.C. reached their peak bloom. In ideal conditions, the ephemeral flowers can last for up to a week, but typically the optimal window for viewing is just about four days before leaves begin to appear. The annual Cherry Blossom Festival attracts over a million visitors—and their selfie sticks—from around the world and features a parade, kite festival, dance performances, music, food, and fireworks.

Crowds along the Tidal Basin are often overwhelming, but if you can overlook the tense family photoshoots and the jettisoning of all social courtesies as people jockey to get that ‘gram, cherry blossom season in D.C. is the prettiest place to ruminate on the fleeting nature of life. Peak bloom usually overlaps with another American rite of passage—the eighth grade field trip to D.C.—and hordes of screaming teens provide visitors with additional reminders of their own mortality.

Cherry blossoms have a rich history in Japan, symbolizing the transience of life. Images of the blossoms—one of the national flowers of Japan—have been used by kamikaze pilots and samurai warriors; references to hanami, or the act of enjoying the blossoms—usually by picnicking under a blooming tree—have been found as far back as the third century AD.

“It’s important to remember the poetic aspect of the trees,” says Joseph Mohr, a National Parks Service ranger who walks around the Tidal Basin daily. “Peak bloom is just four days, which reminds us of the shortness and beauty of life—that’s what’s so special about them.”

Nevertheless, she persisted

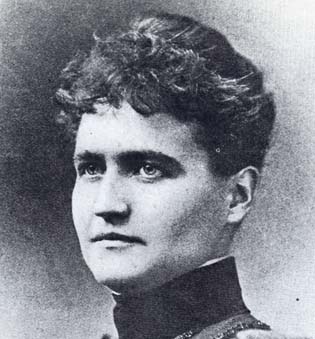

A lot of people were involved in bringing the cherry blossom trees to Washington, D.C., but it all began with one woman’s vision. When Eliza Scidmore, an adventurer and travel writer, returned to the U.S. from a trip to Japan in 1885, she contacted the U.S. Army Superintendent of the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds, proposing that cherry trees be planted along the Potomac waterfront. Like scores of women before and after her, Scidmore’s idea was ignored. Nevertheless, she persisted, and relentlessly contacted every new superintendent for the next 24 years—to no avail.

Meanwhile, plant enthusiast and U.S. Department of Agriculture official Dr. David Fairchild imported 100 of his own cherry trees from Japan in 1906. He planted the trees on his property near Bethesda, Maryland—two-and-a-half hours north of D.C.—to test how well they would adapt to their new environment.

His experiment was a success, and Fairchild gave a lecture on Arbor Day in 1908, proposing that the streets of the nation’s capital be lined with cherries. Scidmore was in attendance, and—presumably not thrilled with the idea of Fairchild mansplaining her original idea to her—decided that she would try to raise the funds necessary to buy the cherry trees herself. Intending to donate the trees to the city, Scidmore appealed to First Lady Helen Herron Taft.

Taft, who had once lived in Japan, was immediately on board, writing to Scidmore: “Thank you very much for your suggestion about the cherry trees. I have taken the matter up and am promised the trees, but I thought perhaps it would be best to make an avenue of them, extending down to the turn in the road, as the other part is still too rough to do any planting. Of course, they could not reflect in the water, but the effect would be very lovely of the long avenue. Let me know what you think about this.”

The day after Taft’s letter was sent, more people got involved: Dr. Jokichi Takamine, a Japanese chemist in D.C. at the time, heard of the plan and asked if Taft would accept a donation of an additional 2,000 trees. The Japanese Consul General in New York, Kokichi Mizuno, suggested that the trees be given as an official gift from Tokyo, and on January 6, 1910, 2,000 cherry trees arrived in Washington.

“They didn’t give us trees because they look nice,” says Mohr. “They gave us trees to share a tradition.”

Bugs and blooms

Unfortunately, the USDA soon discovered that the trees were diseased and infested with insects—President Taft ordered that they be destroyed. Japan sent an additional 3,020 trees to D.C., and on March 27th, Helen Taft and Viscountess Iwa Chinda, wife of the Japanese Ambassador, planted two cherry trees on the northern bank of the Tidal Basin.

The rest of the trees were planted unceremoniously over the next eight years. It wasn’t until 1934 that the city sponsored a three-day celebration centered around the blossoming trees; the celebration expanded to two weeks in 1994 and now runs for nearly four weeks during March and April.

There are a dozen different types of cherry trees in D.C., but the most common are Yoshinos, comprising 70 percent of the collection. The Kwanzan blooms 10 to 14 days after the Yoshinos, producing a showy, pink flower. Weeping cherries have drooping branches and the Fugenzos are notable for their double pink flowers. The Takesimensis is more flood tolerant than other varieties, and the Afterglow is an early bloomer.

The largely ornamental flowers vary in color from white to pink and do produce a cherry, although the fruit is smaller than the cherries you would find at the farmer’s market. “I’ve tasted them,” says Mohr. “They’re very sour, but birds love them.”

The official peak bloom prediction—the point at which 70 percent of the blooms are out—is made by the National Park Service based on historical data, weather forecasts, and by simply observing the trees themselves. One over-achieving tree, known as the indicator tree, consistently blooms seven to 10 days before the others. Located just east of the Jefferson Memorial, the tree is nearly indistinguishable from the others to the casual observer, but Mohr points out that its leaves have already started to appear, once again reliably ahead of its neighbors’.

Paddles the Beaver

Japanese-U.S. relations didn’t remain friendly forever, unfortunately, and on December 11, 1941, four cherry trees were cut down, supposedly in retaliation for the attack on Pearl Harbor. Relations improved after the end of WWII, and in 1958, Japan gifted the city a stone pagoda to symbolize friendship between the two nations. In 1965, they gifted D.C. another 3,800 trees, many of which were planted around the Washington Monument at the direction of Lady Bird Johnson.

Although Fairchild’s experiment proved that the trees could survive in America, they still face challenges, including an increasing threat of climate change-related flooding. As trees die, they are replanted from cuttings to preserve their genetic lineage. In the early 2000s, 400 trees propagated from the surviving 1912 trees were planted, and in 2011, 120 more propagates were gifted back to Japan.

In the late 1990s, beavers gnawing on the trunks of the cherries killed at least five trees. Protective cages were placed around the bases of the trees and some of the offenders were quietly removed from the Tidal Basin area. Mohr says the beavers were “somewhat unwilling participants in the witness relocation program.”

Paddles the Beaver, the official mascot of the Cherry Blossom Festival, was featured on signs urging visitors to not pick the blossoms or climb the trees. Sadly, Paddles didn’t make an appearance at this year’s festival. “Last year, the costume was put into storage while it was still wet and it got moldy,” says Mohr. “Luckily, I don’t fit into the costume.”

Even just walking around the trees can damage their roots, and visitors should be cautious and respectful: No amount of Instagram likes is worth damaging a century-old tree in the process. As the crowds swell, however, accidents do happen and Mohr says that he’s started carrying around a length of rope in the event that he has to pull someone out of the Tidal Basin.

“One woman hit an overhanging branch and fell off of her bicycle into the water. We pulled her out, but she jumped right back in to retrieve her helmet. If we need to pull someone else out twice, we’ll pull them out twice,” he says. “We try not to cut the overhanging branches because they frame photos nicely.”

If you go

The 2022 National Cherry Blossom Festival takes place March 20 to April 17. The main place to view the blossoms is around the Tidal Basin in Washington, D.C. For more information, check out the National Park Service’s cherry blossom page.