New York City isn’t known for its solitude. The city that never sleeps could also be called the city that never shuts up. But those willing to take the subway to the end of the line, hop on a bus for a few stops, and walk down an overgrown path swarming with hungry mosquitoes will be rewarded with something even better than quiet: the sound of waves gently washing over thousands of glass bottles. This calming, clinking sound is brought to you by an unseemly source: the trash of Dead Horse Bay.

Dead Horse Bay is a small body of water in between two inlets near Jamaica Bay in South Brooklyn. Located on the shore of what was once known as Barren Island, it was named for the horse-rendering plants that operated along the coastline from the 1850s until the early 1900s. In the 1950s, landfill was used to connect the island to the mainland—a common practice in a city where land is scarce—but for reasons unknown, the trash was covered with only a thin layer of topsoil.

Thanks to erosion, trash is constantly appearing along the shore—deposited into the bay and washed back up on shore in a continuous cycle—but the best time to find newly-revealed treasures is low tide (consult a tide chart before you make the trek).

Although Dead Horse Bay is not a secret, its remote location means that if you’re lucky, you might have the entire beach to yourself—if you don’t mind sharing it with thousands of bottles, shoe soles, and other remnants of the daily lives of former Brooklyn residents.

Horse bones and horseshoe crabs

Like most of New York City, the Gateway National Recreation Area—which includes beaches and wildlife refuges managed by the National Park Service—has a sordid past. It may be hard to see now, but if you look past the idyllic bike paths and serene shores, you can find remnants of the area’s former life as an industrial hub.

Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photos: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan The proverbial kitchen sink. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photos: Alexandra Charitan An old bicycle. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

In the late 1800s, Barren Island was even more inhospitable than its name suggests. The city designated the sparsely populated, remote island as the destination for all of its waste, including slaughterhouse offal and dead horses. At its peak, the island had nearly 2,000 residents and, according to the New Yorker, “in 1879 a court ruled that a Brooklyn railroad company could legally turn away passengers who worked in the rendering plants because their clothes smelled so terrible.”

In a city reliant on horses for transportation, New York had no shortage of carcasses to send to the island. The plants rendered their bodies into myriad products including glue, fertilizer, and buttons. After the introduction of the automobile drastically reduced the need for horses, the last plant closed in 1921, and a few dozen human holdouts left the island for good in 1942. The island was soon connected to the mainland and became the site of the city’s first municipal airport.

Allison C. Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer and licensed New York City sightseeing guide. She first discovered Dead Horse Bay through word of mouth when she moved to the city ten years ago. “Although the whole city was new to me, I found these overlooked corners of the city to be fascinating,” she says. “Dead Horse Bay is kind of the shadow of the city, with its history of imminent domain, toxic industry, and the waste of past generations.”

“Dead Horse Bay is kind of the shadow of the city, with its history of imminent domain, toxic industry, and the waste of past generations.”

Nearly a century later, mementos from the island’s macabre past can still be found washing up on shore. Most of the horse bones that you’ll find were cut into small pieces before they were dumped into the bay, and thankfully they’ve been tumbled clean by time.

The titular horses aren’t the only animals to meet their maker at Dead Horse Bay. Depending on the season, you might find yourself stepping over horseshoe crabs, seagulls, and pungent fish.

Horseshoe crabs emerge in May and June to lay eggs on the beach. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photos: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan A rusty iron. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Horseshoe crabs don’t just look prehistoric, they actually are prehistoric. At 1.2 billion years old, the species predates dinosaurs and they are considered to be “living fossils.” Every May and June, according to the New York City Parks Department, the crabs emerge from the Atlantic Ocean to lay their eggs on the beaches (there’s an entire society devoted to monitoring this process). Females can lay up to 20,000 eggs at one time—attracting not only male crabs hoping to fertilize a batch of eggs, but thousands of migratory birds in search of a protein-rich feast.

The area is “oddly a place of natural discovery, the way you have to navigate through the tall grass to get to the beach,” says Meier. “A rabbit once jumped out on the trail ahead of me—definitely the only time that’s happened to me in New York City.”

Bottles and boats

In a place referred to as “glass bottle beach,” it’s no surprise that the most common item you’ll come across is the glass bottle. Before plastic or aluminum containers, almost every liquid or cream—bleach, soda, make-up, shoe polish—came in a glass bottle. Some of the bottles—made of green, clear, brown or blue glass—still retain their graphics, outlasting the companies that made them by decades.

Local and national brands are represented, some with their slogans still readable: Pick Upper, an alkalizing beverage “aids to give you that needed pick up the morning after the night before.” Another bottle confidently declares that consuming its product is “always a pleasure.”

Photo: Alexandra Charitan The Marine Parkway Bridge leads to the beach at Jacob Riis park. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photos: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photos: Alexandra Charitan Rusty keys. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

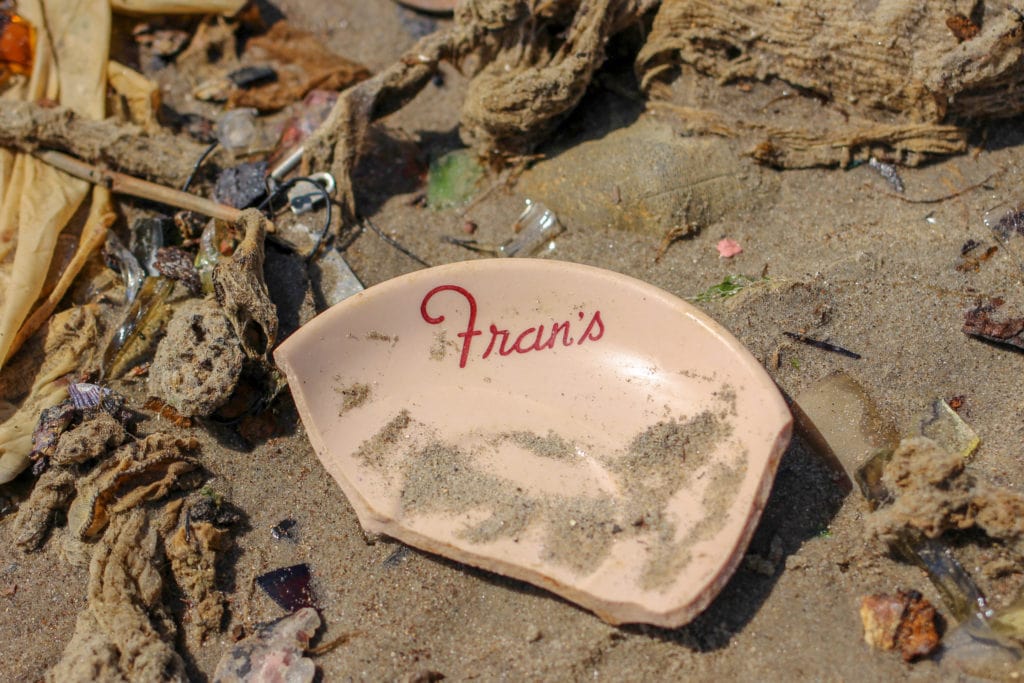

Bits of broken china hint at their former lives, revealing fragmented names of restaurants and pottery makers. I’ve seen almost anything you can think of wash up on the beach of Dead Horse Bay: tubes of paint, an iron, vinyl records, plastic dolls, tires, a ceramic cow foot, a bathroom scale, a tube of toothpaste, rusty keys, wallets, a cash register, a roll of film, can openers, toilet seats, basketballs, a safe—even the proverbial kitchen sink.

“I never feel like I’m returning to the same place,” says Meier. “The shore is always changing, with some days the sand littered with old shoes, others the most abundant thing is green glass or some mysterious hulking metal object. But the fact that it’s this overlooked sliver of neglect is always consistent.”

While glass bottles are by far the most common type of trash to find at Dead Horse Bay, well-worn shoes are also a common sight. High heels, oxfords, and baby shoes serve as poignant reminders of the people that once inhabited this city—old soles worn by time and forever separated from their mates.

Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photos: Alexandra Charitan Lundy Bros., a beloved Sheepshead Bay restaurant, closed in 2007. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photos: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Abandoned boats line the shore with no clue as to how or why they got there—just another example of how almost nothing at Dead Horse Bay stays the same for long.

“I photographed a beached boat on one visit, only to find it gone and a different boat in its place on the next,” says Meier.

Trash or treasure?

The idea that our oceans and beaches are filled with trash is not new, but recently beach trash has become an easy way to illustrate the growing global problem of pollution, particularly from non-biodegradable plastics. And opting out of a straw with our Starbucks isn’t going to solve the problem: According to National Geographic, eight million tons of plastic trash ends up in the world’s oceans every year.

But the idea that “one man’s trash is another’s treasure” could be Dead Horse Bay’s official slogan. While it’s technically illegal to remove anything from the national park land surrounding Dead Horse Bay, treasure hunters are not deterred.

In 2017, when Meier was invited to curate an art show at UrbanGlass, NYC’s largest artist glass studio, she immediately thought of the glass on bottle beach. The show, Dead Horse Bay: The Glass Graveyard of Brooklyn, exhibited pieces made with items collected from the area, in addition to photography, video, and other installations.

Meier says that the artists were successful in transforming trash into beautiful art. “David Horvitz exhibited these amazing, insanely delicate vessels made from melted sea glass—objects that looked ready to shatter at a touch,” says Meier. Other pieces were created to shed light on the issues of waste and invasive plant species that thrive in abandoned places.

Photo: Alexandra Charitan A bit of a Clorox bottle. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A rusted-out safe. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan The path leading to the bay can be a bit overgrown with tall grass. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Because the trash on the beach comes from actual landfill, some visitors seem to think this gives them a free pass to leave their current-day trash behind. Maybe it’s just a matter of perspective, but I feel bad for the people of the future if all they get to scavenge for is our left behind Doritos bags and plastic Gatorade bottles, while we fill our backpacks with beautiful soda bottles and intricately patterned bits of china.

For better or worse, Meier says, Dead Horse Bay “is a vivid reminder that everything we throw away is never really gone, and the past is still under our feet.”

If you go

Take the No. 2 or 5 trains to Brooklyn College-Flatbush Avenue and then a Q35 bus seven stops to the Flatbush Ave and Ryan Visitor Center stop (across from Floyd Bennett Field and right before the bridge). The path to the beach can be overgrown so bring bug spray.