When I was a child, my family often made the 9-hour drive from our house in Houston, Texas, to my grandma’s house in Amarillo. The city, located in the state’s Panhandle, is surrounded by open, flat plains; the air smells unmistakably of cows. We visited the colorful cars at Cadillac Ranch, hiked through Palo Duro Canyon State Park, and stuffed ourselves at The Big Texan Steak Ranch.

During a more recent trip, my parents and I came across a less-known attraction: a collection of painted traffic signs scattered across Amarillo, none of which have anything to do with actual rules of the road. We spotted our first sign in the eastern part of the city, along the main strip of Amarillo Boulevard. Standing in the shadow of a billboard in front of a laundry center, the yellow sign with a bold, black font read: “Sometimes we tell meaningless stories because that’s the way it is.”

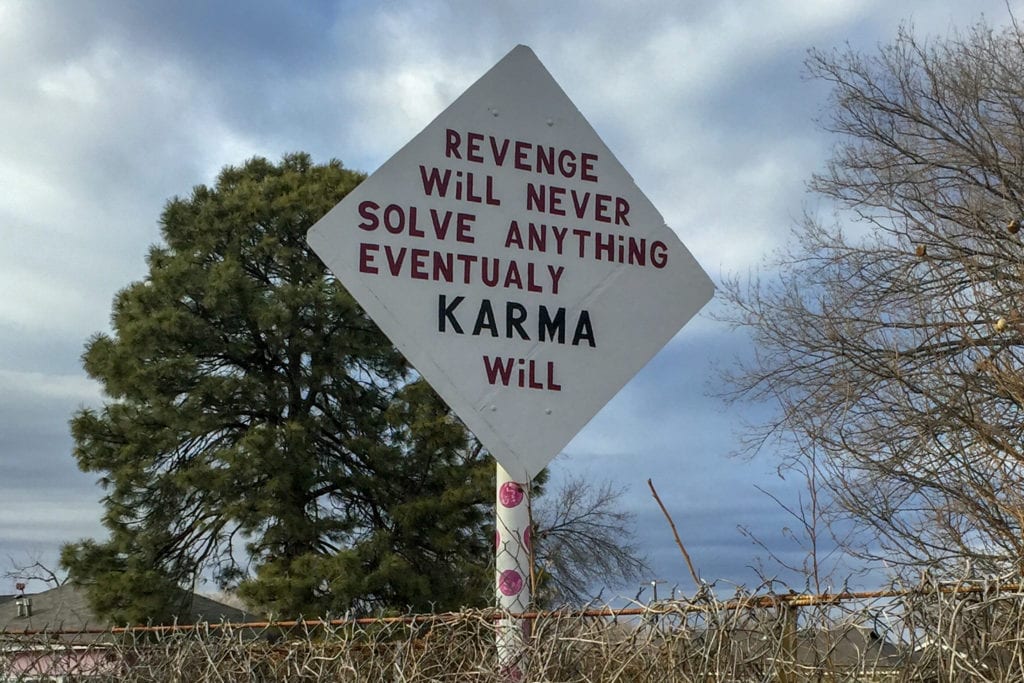

Over the course of three days, we explored neighborhoods in a methodical grid, driving past row after row of houses, searching for more signs. While we had no idea what message or art the next sign would bear, we trained our eyes to pinpoint what they all had in common: that regulation-sized diamond shape normally used to signal a pedestrian walkway or dead end.

Some signs have illustrations, some just a few words, and others display a full paragraph of text. Some are clean and bright, others have noticeable wear and tear. In total, we found more than 185 signs.

Art history

While many people refer to the collection of signs as the “Dynamite Museum,” this is actually the name of the artist collective behind them. Jon Revett, an artist and assistant professor of painting and drawing at West Texas A&M University, became involved with the Dynamite Museum in the mid-’90s. He explains that the collective’s name comes from the fact that the group, funded by eccentric millionaire Stanley Marsh 3 (who also sponsored Cadillac Ranch), wanted to “blow up” the idea of what an art museum is supposed to be.

Revett says that the Sign Project is the Dynamite Museum’s most successful work, and the Amarillo tourism website claims it was once the largest urban art project in the world. While there’s no specific number on record, Revett guesses about 3,000 signs were made and installed, a majority of which stand (or stood) on private property in Amarillo. There are also some located along historic Route 66 in Adrian, a small town 50 miles west of Amarillo.

To choose the artwork for each sign, Revett says they would go through different themes such as Charles Bukowski’s writings, or images of pin-up girls. Jonathan Elmore, an actor and writer who joined the Dynamite Museum in 1991, says many of the signs were a product of stray thoughts that Marsh 3 had.

To manufacture the signs, which cost between $300 and $1,000 each, the Dynamite Museum turned to local sign companies. Then they connected with property owners about placement.

“I drove around in the company car—a 1959 pink Cadillac,” Revett says. “We would target specific neighborhoods and I would stop if I saw people in their yards. I had a stack of Polaroids of the current signs and I would ask if they wanted one. If they did, then an entire procession of cars and trucks would show up on the weekend and put the sign in the yard.”

During his time working on the project, Elmore began experimenting with hand-painted signs using metal or wood from local suppliers. “Making art that people are going to see unexpectedly on their way to get their car washed or their prescription filled made me feel like I was a graffiti artist without the threat of going to jail for destruction of property,” he says.

For the people

Revett estimates that less than 1,000 signs still stand. Some have been removed by landlords; others have been stolen, destroyed, or fallen prey to the elements. There may not be a complete database of all the signs and their locations, but Matthew Williams, an Amarillo-based artist who designed more than 150 signs from 1995 to 1998, is currently working to catalog the remaining signs before they’re gone forever. He runs the Dynamite Museum’s Facebook page and his former students set up its Instagram page.

As the number of signs has dwindled over the years, the project has also been under scrutiny for its connection to Marsh 3, who was indicted on sexual assault charges a year before his death in 2014. According to a NewsChannel 10 report, a homeowner requested that her sign be repainted after the allegations came to light. In 2015, Houston-based Dolcefino Consulting launched a social media campaign called “Erase Marsh Madness,” calling for the removal of the signs on behalf of Marsh’s victims.

“It is important to understand that while Marsh was a member and patron of the Dynamite Museum, it was a group of artists and we all contributed our ideas,” Revett says.

Elmore agrees. “I know there was a call to take down the signs when he was accused of misconduct, but the signs weren’t really Stanley’s anymore,” he says. “They were my signs. They were other artists’ signs. They were Amarillo’s signs.”

Williams recommends heading to Amarillo’s San Jacinto District and South Washington area if you’re looking to check out the signs. “The best thing about the signs is they work like an Easter egg hunt—you never know when you might run into a piece of outdoor contemporary art in a quiet neighborhood,” he says.

If you go

Remember that many signs are on private property so be respectful when checking them out and taking photos.