Marion Duckworth Smith believes in love at first sight. She was on a second date with Michael Smith, a New York City publisher, when he suggested that they visit his cemetery. It was a miserably cold night in November, 1979, and Duckworth Smith was skeptical.

“I said, ‘No guy owns his own cemetery,’” she recalls. “And he said, ‘Well, I do.’”

Michael not only owned a cemetery, but the surrounding one-acre, double lot in East Elmhurst, Queens. He had purchased the property and its two-story, Dutch farmhouse (built in the 1650s) in 1975, but he hadn’t lived there in years. The electricity had been turned off long ago, so he left Duckworth Smith alone in the small, overgrown cemetery while he went into the house to scrounge up a few candles.

“So I’m waiting out there, freezing, surrounded by old vines and I’m looking around thinking, ‘I don’t believe this whole thing. I meet the man of my dreams, he’s got the house of my dreams, and a cemetery,’” she says.

The cemetery’s gate. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The cemetery has 130-plus burials. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The former caretaker of the cemetery had 47 dogs. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Most of the inscriptions on the headstones have worn away. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Marion’s mother, brother, sister, and husband are buried in her cemetery. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The cemetery contains Rikers and their descendants. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

When Michael located the candles, he invited Duckworth Smith inside, and she fell instantly in love. “I’m standing in the center hallway and I get goosebumps,” she says. “I thought, ‘Wow, this house has been waiting for me. I’m going to bring it back to life and it’s going to bring me back to life.’ And I did—and it did—and it’s been wonderful.”

Duckworth Smith gives tours of the Lent-Riker-Smith Homestead on select weekends throughout the year and she is as much—or more—of a draw as her historic home. Like Willy Wonka, she only opens up her chocolate factory sporadically; instead of Oompa Loompas, five cats roam the property and the golden ticket is an advance reservation.

The homestead

I visit Duckworth Smith on a bright and clear afternoon in late September. She offers to make lemonade and suggests that I arrive at 3 p.m. when the light is ideal. She’s right; if I didn’t know better, I’d never guess that her humble abode is more than 360 years old. The same can be said of Duckworth Smith herself, who, despite her nearly 80 years, doesn’t look much different today than she did when she married Michael and officially moved into her dream house in 1983.

Built by Abraham Riker when New York was still New Amsterdam, the house was one of many farmhouses owned by the Riker family. The oldest continually-inhabited private residence in New York City, the home has been owned by just three families: the Riker-Lents, William Gooth (a Riker family secretary), and the Smiths. In 1938, much of the Rikers’ land was sold to the city, including the eponymous East River island, currently home to New York City’s notorious jail complex. A more elaborate house, built in the 1800s just to the east, was torn down to make way for LaGuardia Airport.

Michael, who rented the house in the 1960s for $100 a month before he bought it for $65,000, loved the property—but his wife at the time did not. She was an actress and thought the house’s north Queens location was too rural; she wanted to be in Manhattan. “How could she not be happy here?” Duckworth Smith asks.

Although Michael’s first wife got her wish, the marriage didn’t last. When he met Duckworth Smith, Michael gave her a choice: Did she want to live in his seven-and-a-half-room apartment on East 57th Street, or the Lent-Riker homestead?

“Well, I wanted both,” Duckworth Smith says, laughing. “But when I was a little girl, this was the dream. I always wanted an old house to fix up.” Michael’s ex-wife took the Manhattan apartment, and Duckworth Smith got her old house—and promptly got to work fixing it up.

Treasures in the attic

During the several years it sat vacant, the house had fallen into disrepair. It was robbed and vandalized; the cemetery was desecrated. The shutter-less facade was crumbling. “It had become the haunted house of the neighborhood,” Duckworth Smith says.

Cleaning out the attic was Duckworth Smith’s first project. Accessible only by a small trap door, it had been untouched for 100 years. In the three-month process, she unearthed a treasure-trove of Riker family history including glass negatives, a large pot belly stove, ledgers, maps, and colored glass bottles.

The Rikers were bankers, financiers, and pharmacists. The bottles, Duckworth Smith says, used to hold prescription liquids, “tonics and benign things.” The last will and testament of John L. Riker indicated that the family, despite their large land holdings, wasn’t especially wealthy. “I thought it was fascinating,” Duckworth Smith says. “The eldest son got the mourning suit, the family bed, and the tools.”

The keeping room. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The kitchen. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Portraits of Duckworth Smith’s mother (left) and sister (right). | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

One thing she didn’t find? Love letters. “I would have liked that,” she says. “When I came here the house was sad, the house was misunderstood, the house was neglected. [Cleaning the attic] was so much fun. I would sit up there on a day like this—I’d open the window and look down. You have an aerial view of the cemetery and it was so tranquil.”

Duckworth Smith has always loved visiting cemeteries. She calls them “outdoor art galleries,” and owning her own has been a dream come true. “It’s so nifty,” she says. The oldest internments date back to 1744, and more than 130 Rikers and their descendants, employees, and pets are buried in the small cemetery. A 1919 survey of the plots records poignant inscriptions, many of which are no longer visible: “Weep not my friends all dear, I am not dead but sleeping here; The debt is paid, the grave you see. Prepare for death and follow me.”

When Michael died in 2010, he was buried here alongside Duckworth Smith’s mother, brother, sister, and several cats. Duckworth Smith is prepared to follow them when her time comes, but she has no plans to rest in peace. “I’ll be here to haunt anybody who comes along and tries to destroy my good work,” she says.

A project lady

Duckworth Smith was born Marion Ascenzi in Williamsburg. “When nobody wanted to live there,” she says. She grew up in the shadow of a “drop-dead gorgeous” sister, and their mother was a “master pastelist.” Several of her mother’s still lifes hang in the homestead’s kitchen.

“I finally realized why I’m such a show-off,” Duckworth Smith says. “My sister was the beauty in the family and it was hard. I had to fight for every compliment. But I made up for it as we got older.”

She worked for her first husband, who owned a photography studio on 23rd Street in Manhattan, for 22 years. Although Duckworth Smith resisted learning the technical aspects of the business, “I learned so much just by watching him work,” she says. “But I wanted to spread my wings.” Just before she turned 40, the couple divorced.

When Duckworth Smith needed a job, a friend recommended her to Michael Smith, who needed a proofreader for the directories he published. “I went up for the job and met the man, got the job, quit the job, kept the man,” she says.

After wooing Duckworth Smith with her own cemetery and historic home, Michael struggled to find gifts for his new bride. “He eventually ran out of jewelry to buy me and one day comes home with a camera,” she says. “So I think, ‘Gee, I finally want to be a photographer.’”

Her photos have appeared in calendars and greeting cards sold in stores all over the world—from New York’s Fifth Avenue to Paris’s Champs-Élysées. In 2004, The Romantic Garden, a coffee-table book featuring Duckworth Smith’s photos of her home’s lush gardens, was published.

“People asked, ‘How long did it take you to do the book, Marion?’ And I said, ‘Well the book took a year but the garden took 25,’” she says.

It’s obvious that the Smiths worked hard to restore the home, both inside and out. Throughout the years, the farmhouse operated as a tavern, boarding house, and possibly even a bordello. Today, the “keeping room” looks exactly how it would have in the 1600s, with original wide-plank floors, hand-hewn beams, and a plain pine fireplace.

“I’m a project lady,” Duckworth Smith says. “I opened a fortune cookie once and it said ‘Achievement is the ultimate high.’ And for me that’s true. I don’t need a new dress to go to the party, the real thrill is to achieve something. This is my greatest accomplishment—the restoration of this house.”

Chalkware centerfold

The Smiths donated a large portion of their Riker memorabilia to the Brooklyn Historical Society and today, the house is an elaborate tapestry of its past and current owners. Collecting and a love of “showing off” is clearly in Duckworth Smith’s DNA. Her sister, after more than a decade working as one of the original bunnies at New York’s famous Playboy Club, worked at an antique shop called Good Old Things on Lexington Avenue. She died a year-and-a-half ago and Duckworth Smith is still sorting through her belongings, which included movie magazines from the 1920s and dozens of Limoges soup tureens.

“Collectors—we’re one step before hoarders, don’t you think?” she says.

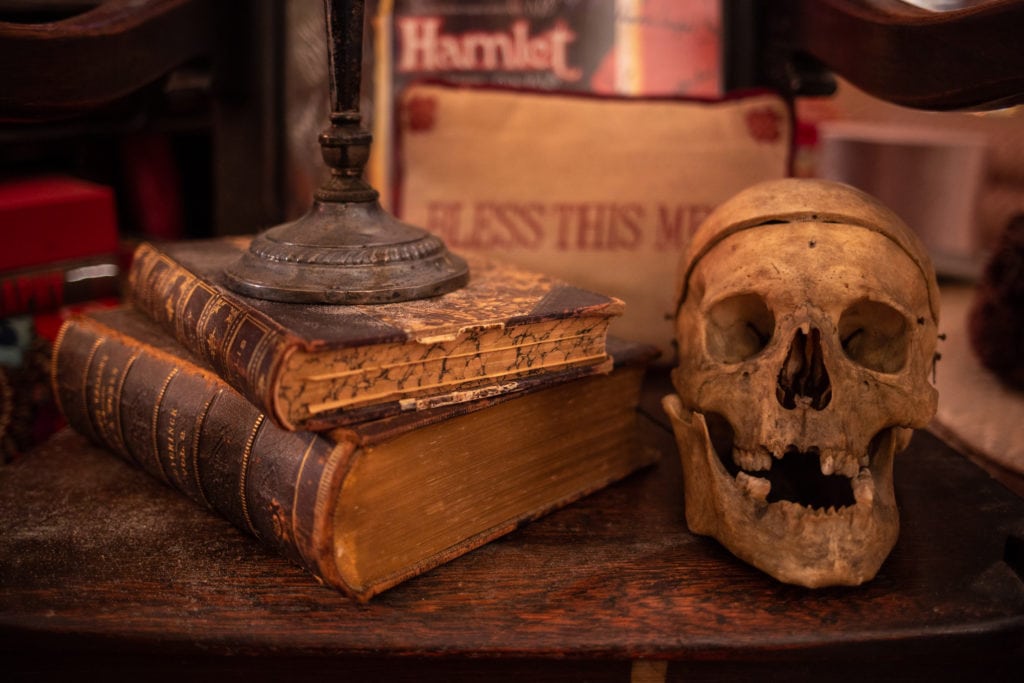

When Duckworth Smith says, “It’s exciting to know that you own a piece of history,” it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly she’s talking about—the house itself, or one of her many collections contained within. Over the course of my visit, she points out a human skull, her father’s WWI medals, a perambulator from the Atlantic City boardwalk, ventriloquist dolls, a mannequin hand that she stole from the now-defunct department store B. Altman, several family portraits, a hand-painted child’s desk, and vintage glassware.

A human skull. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Duckworth Smith’s collection of Broadway memorabilia. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Duckworth Smith stole a mannequin hand when B. Altman closed. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Tommy Tune’s tap shoes and Chita Rivera’s cabaret shoes. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Duckworth Smith’s glassware collection. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

A tiny sun porch houses Duckworth Smith’s vintage toy collection. She’s particularly proud of a plain, weathered carousel horse from Coney Island (circa 1917) that she acquired after it failed to sell at an auction. “She has no makeup, no jewelry, nobody wanted her,” she says. “But once I brought her here—to the 360-year-old farmhouse—she’s perfect, she’s a star.”

The same could be said of Duckworth Smith, who has had her share of star-making moments in the 30-plus years since she first came to the homestead. “I’ve been in the New York Times six times,” she says, and she has the clippings displayed beneath glass on her kitchen counter to prove it.

“Collectors—we’re one step before hoarders, don’t you think?”

After her beloved brother died of AIDS in 1988, Duckworth Smith devoted her life to raising money for the charity Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS. She purchased walk-on roles in several Broadway shows, beginning with Follies in 1991 (President Ronald Reagan attended the performance and, again, she has a photo to prove it). “My brother was a singer and his dream was to appear on the Broadway stage,” she says. “He never made it, so I did it for him.”

Duckworth Smith has also amassed a collection of Broadway memorabilia including Carol Channing’s necklace from Hello, Dolly!, Glenn Close’s ring from Sunset Boulevard, Tommy Tune’s tap shoes, an original top hat from A Chorus Line, and Chita Rivera’s cabaret shoes. “I happen to have the same shoe size as Chita,” she says.

Duckworth Smith’s carnival chalkware collection. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Ventriloquist doll collection. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A carousel horse from Coney Island. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Charlie McCarthy dolls. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A vintage doll. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Her collection of carnival chalkware dolls—including several Snow Whites and Donald Ducks—even snagged her a feature in the New York Post. “At 75 years old I finally became a centerfold,” she says.

The next 300 years

Although Duckworth Smith intends to stay in her beloved home for all of eternity, she’s realistic about its prospects after her death. The house was one of the first structures to be given landmark status after the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission was formed in the 1960s, and it’s listed on the National Register of Historic places. However, Duckworth Smith says that the protections aren’t foolproof: “When you’re a landmark in Queens, you’re a step child.”

Fifteen years ago, the Smiths were in negotiations with the New York City Parks commissioner, but a deal that would have granted them lifetime tenancy and an operating stipend ultimately fell through. “It was probably for the best,” Duckworth Smith says, sighting the restrictions that come with such deals. “We would have been owned by them.”

Duckworth Smith’s only daughter lives in California and is uninterested in the historic home. “I’m a widow alone here and I have to find a way to stay,” she says. “It’s a lot to maintain.” Ideally, she would like to see the house continue on as a museum and park for the next three centuries, and beyond.

In New York City, a one-acre backyard is virtually unheard of—but Duckworth Smith’s secret garden is equal parts whimsy and work. In 2012, Superstorm Sandy destroyed a gazebo. “That broke my heart,” she says. This summer, a storm flooded the home’s basement and lightning split a tree over the fence and into the yard. When Duckworth Smith balked at the $3,000 removal fee, her handyman of 30 years improvised, bracing the splintered tree and turning adversity into art. “It’s like a sculpture,” she says. “I thought, ‘Someone’s gonna love this for a fashion shoot.’”

The Lent-Riker-Smith homestead has indeed been featured in photo shoots, most recently for Coach bags and shoes. But while Duckworth Smith is clearly comfortable in the spotlight, she’s too protective of her home and its delicate treasures to give a film crew free rein. “Movies are big money but I’d never live through it,” she says. “These photo shoots feel like a home invasion.”

For Duckworth Smith, sharing her home with the public has always been a labor of love. “These tours—it’s cat food and cab fare money,” she says. “It’s not paying my property taxes.”

A great romance

All great love affairs have their ups and downs, and at times Duckworth Smith seems conflicted. On the one hand, she clearly loves showing off, and she’s good at it. But for all of its historic value, this is still her private residence. “I have the gate padlocked all the time because people just walk in,” she says. “They see the landmark plaque, they see a house that’s unique, and they think they can just walk in. And that’s not fun after a while.”

As if on cue, a man rides up on a bicycle just as Duckworth Smith is locking her ivy-covered gate. He lives nearby, and is curious about the historic home; on a quiet street filled with unremarkable row houses and bland, brick apartment buildings, the 15th-century Dutch farmhouse sticks out. Duckworth Smith is tired and a bit annoyed—“See, this happens all the time,” she whispers—but she hands him a business card and urges him to return in a few weeks for a proper tour.

We’re losing the afternoon light, but I think I see a smile emerging from the shade of Duckworth Smith’s wide-brimmed hat. “I love my home,” she says, disappearing behind the red Dutch front door. “This has been an adventure, a journey, a romance.”

If you go

The Lent-Riker-Smith Homestead will be open for tours on Saturdays October 12, 19, 26, and November 2 at 3:00 p.m., advance reservations are required.