Some of the best art in New York City isn’t on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for sale at Sotheby’s, or hanging in a Chelsea gallery. Less than 20 miles east of the more famous venues, tucked away on the sprawling campus of Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens, is a treasure trove of art just as good as—if not better than—what you’ll find on the walls of MOMA or the Whitney.

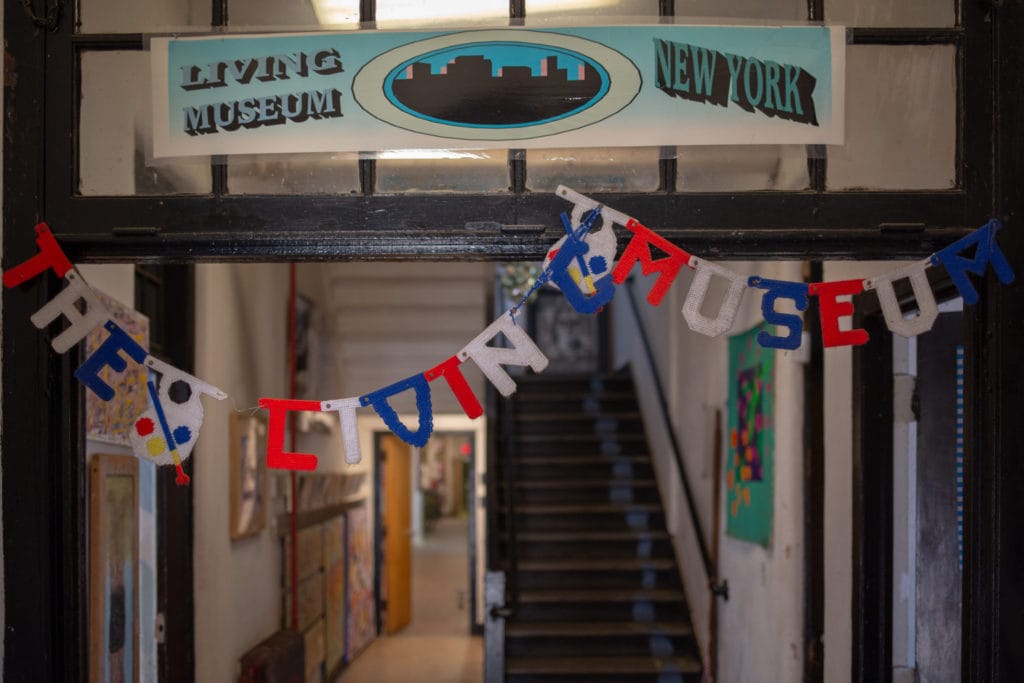

The Living Museum was founded in 1983 by Bolek Greczynski and Dr. Janos Marton, friends from art school. Marton was working at Creedmoor as a psychologist when he and Greczynski started the Living Museum as “an oasis where it is alright that you have symptoms of disturbances, it’s alright to be mad or be crazy or whatever society calls the kind of behavior you are exhibiting,” as Marton says in a documentary filmed at the museum.

-

Living Museum founders Dr. Janos Marton, left and Bolek Greczynski, right. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The Living Museum is located in Creedmoor’s former cafeteria. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Creedmoor, founded in 1912, opened with just 32 patients. By 1959, that number had ballooned to 7,000. The 300-acre campus comprises more than 50 buildings and once had gardens, a swimming pool, a theater, and a television studio. Patients worked in the kitchens, helped with laundry, grew their own food, and raised livestock. A trend toward deinstitutionalizing patients began in the 1960s, and today the psychiatric center only has a few hundred beds.

Greczynski, an artist himself, died in 1995, but Marton still runs the museum, which is part working art studio and part gallery. The museum is housed in Creedmoor’s former cafeteria. As the population of Creedmoor declined, its older buildings were either repurposed or abandoned. The peeling paint, rusty metal catwalks, and defunct kitchen equipment scattered around the museum creates a sharp contrast with the colorful and often poignant art layered on top.

-

A ripped up straight jacket. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

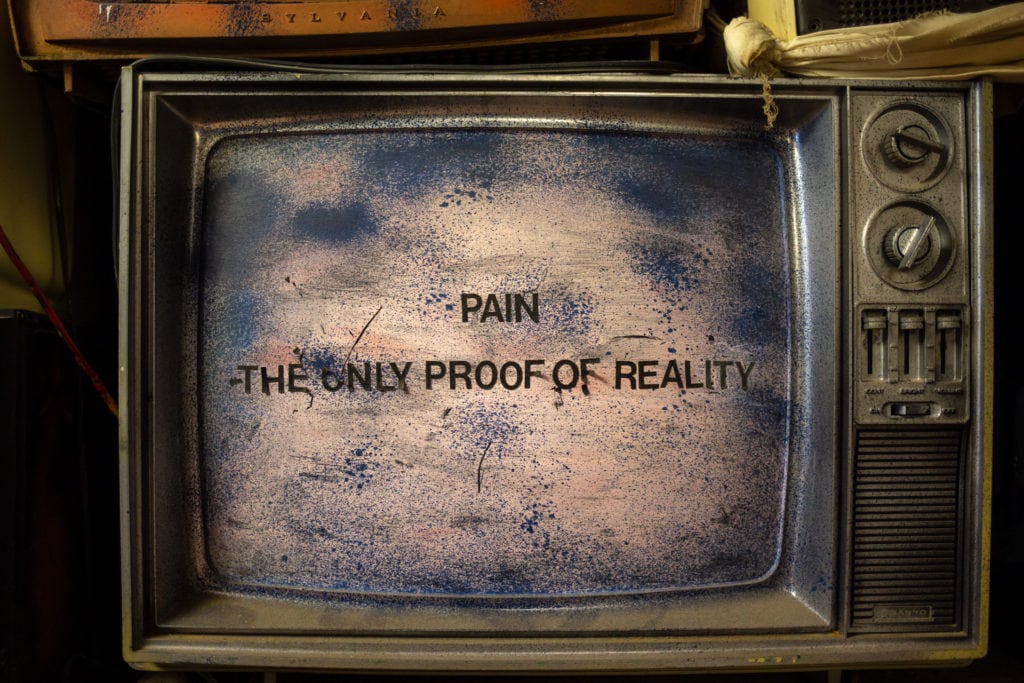

A wall of painted TVs sits in a dark room on the second floor. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

An altar filled with religious-themed art occupies an entire room. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Detail from the TV wall. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

There is art at the museum in every style and medium. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

An old dentist chair sits surrounded by art. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

A lifeline

Stephen Spagnoli, who has battled depression and chronic pain, found out about the Living Museum at a job fair. When someone asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, he replied, “An artist.” He was referred to Creedmoor and he’s been coming to the museum a few times a week for the past fifteen years.

“I always had the artistic ability, but I never had the space,” Spagnoli says. “I opened the door [to the Living Museum] and it was unbelievable. I had found a community.”

-

Stephen Spagnoli’s studio space is located in a former meat freezer. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

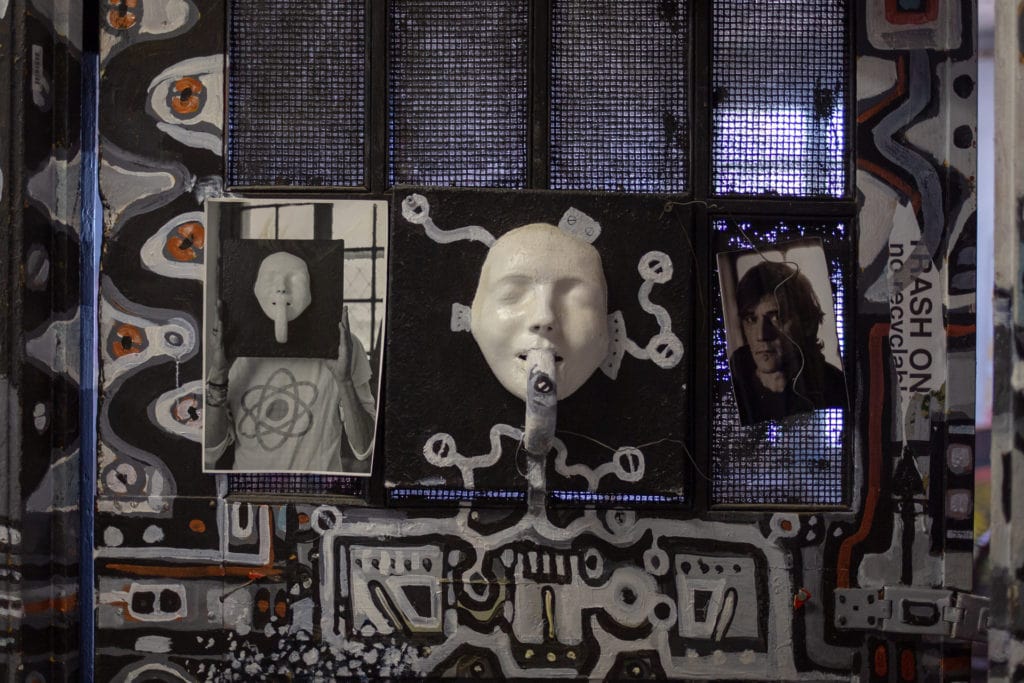

Spagnoli’s studio space. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A painting by Spagnoli representing neuropathic pain. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Spagnoli’s space is covered in a pattern he painted himself. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Two paintings by Spagnoli. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The door to his studio, located in a former meat freezer, is covered with an intricate, grayscale pattern that Spagnoli painted. The design spills onto the floor and covers everything in its path, including a small stool. Spagnoli channels his, at times intense, physical and emotional pain into his artwork, also producing canvasses streaked through with orange. It’s a visceral representation of nerve pain that almost hurts to look at.

“I opened the door [to the Living Museum] and it was unbelievable. I had found a community.”

“Art is not just what is happening in the frame, but what is happening in your brain and what is happening in your life, a consequence of what is in front of you,” says Marton. “In that sense, the whole Living Museum is a conceptual art piece—not just the paintings, which are beautiful, but how they come about.”

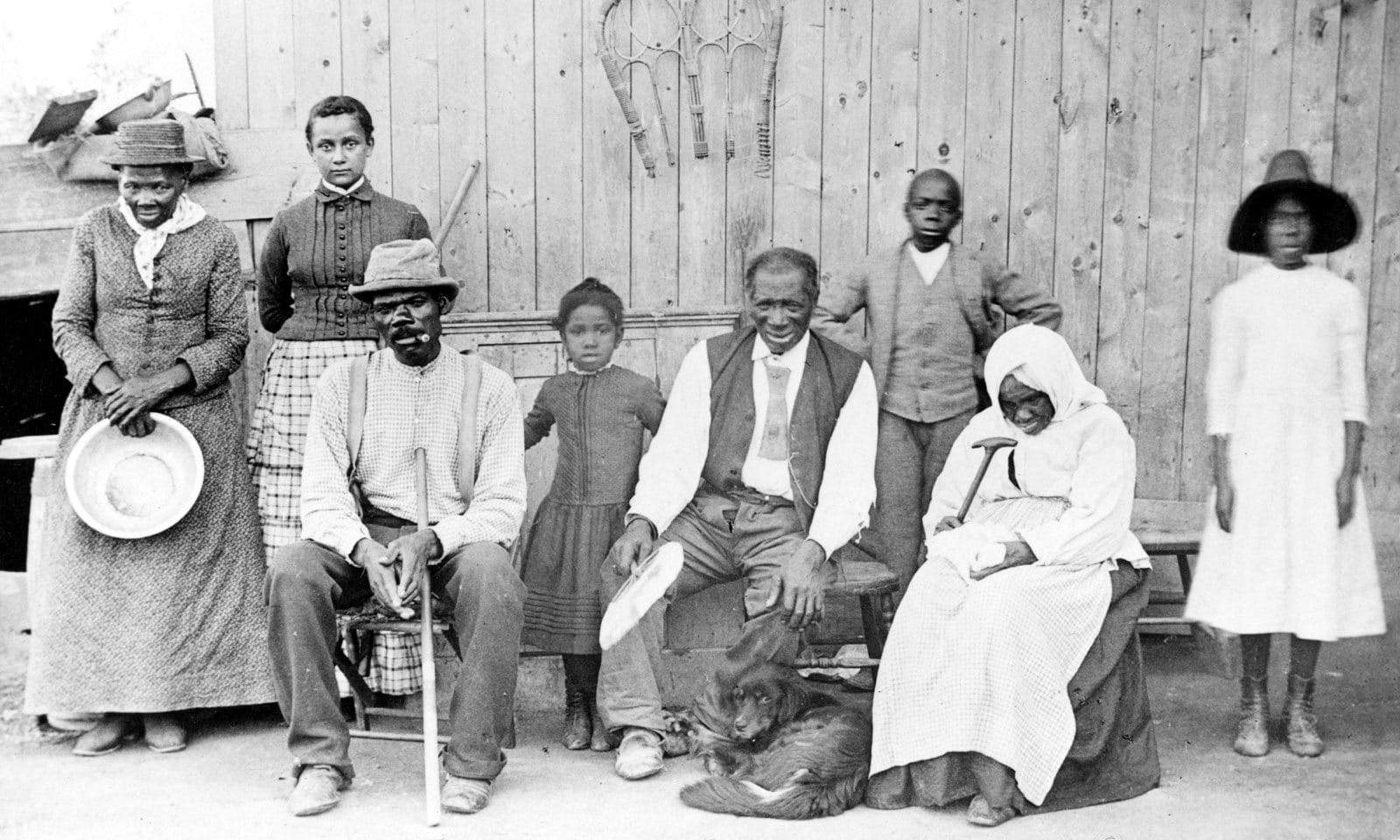

The artists here aren’t struggling with anything that hasn’t haunted generations of artists before them, but at the Living Museum, mental illness isn’t the exception, it’s the rule. “Mental illness can mean a lot of things,” Spagnoli says. “There is a great diversity in who uses this space—the museum is a lifeline for a lot of people.”

-

The people who utilize the Living Museum are a diverse group. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

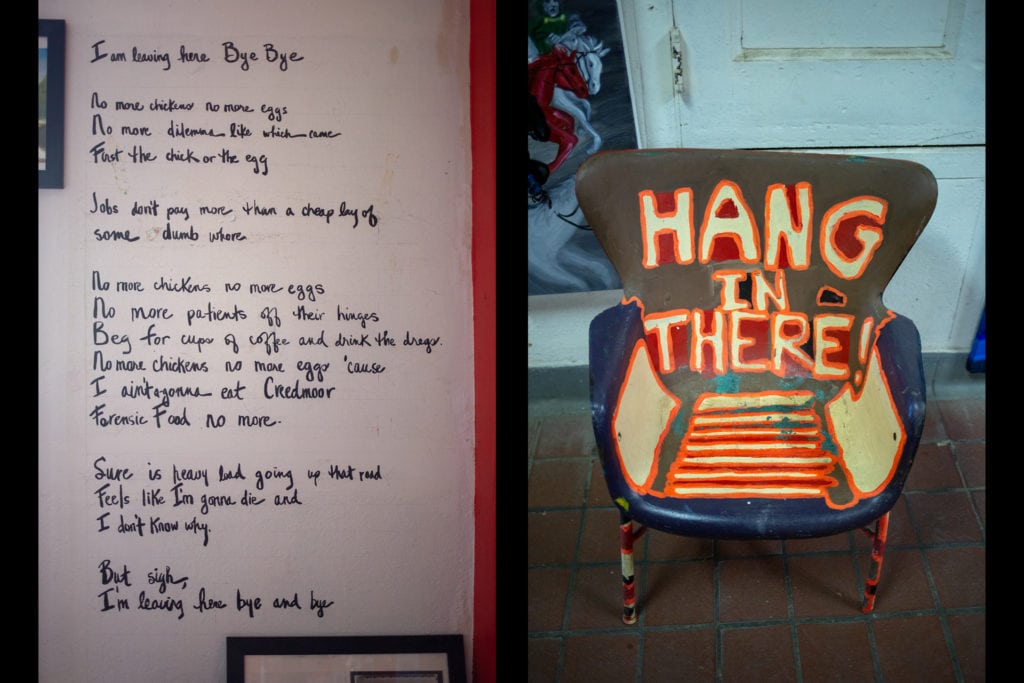

A poem written on the wall and a painted chair. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Portraits of Dr. Marton done by artists at the Living Museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A sculpture made from wire hangers. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The entrance to the Living Museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Art as therapy

Although not everyone who creates art within the confines of the space is a current Creedmoor patient, patient confidentiality laws sometimes hinder the museum in publicizing its artists’ work. Some of the artists offer prints of their work, but others lack money and resources; others are hesitant to sell their deeply personal work at all, and most visitors to the museum don’t come with the intention of buying art.

Romanticizing mental illness as a fuel for creativity is a dangerous game, one that can make people reluctant to seek treatment. But at the Living Museum, art is a positive force; getting help doesn’t mean you stop creating art—in fact, the opposite is true. The creation of art is, in itself, the therapy.

The creation of art is, in itself, the therapy.

Although the results may be similar, the Living Museum is not a traditionally structured art therapy program. Participants are invited (through a referral process) to “feel out the space and make a project for themselves,” says Diona Ceniza, an art therapist at Creedmoor. Volunteers and staff help out wherever is needed, but people are given free reign to create.

-

Plastic dolls strung from the ceiling. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The garden room is full of living plants. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A creepy doll. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Portraits created at the Living Museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A painting of Albert Einstein on a straight jacket. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The Living Museum also has a house band. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Anyone can visit the Living Museum, but most of its visitors are doctors from overseas, hoping to replicate the program in their home countries. Similar spaces have been implemented in Korea, Switzerland, and the Netherlands.

The museum is a “safe space for artists,” Cenzia says. “It feels radically different” than anything she’s seen working as an art therapist, and she says everyone at the Living Museum—staff, volunteers, and patients—are on equal footing. “The museum really is a living, breathing thing.”

“The trick to it is that if you just produce art here it becomes therapeutic in that you change your identity. You change your identity from that of the mental patient who is hospitalized, locked up, to that of an artist,” Marton says.

Honest art

Drew Mulfall creates incredibly detailed ink drawings using only a ballpoint pen, in addition to painting colorful abstracts and landscapes. His struggles with drugs and alcohol brought him to Creedmoor.

“The museum has been a savior for me,” Mulfall says. “My art has gotten to the point where I am satisfied with it. I feel I’m finally contributing something meaningful. The weight is gone and it’s only because of the museum and Dr. Marton.”

-

Drew Mulfall paints colorful abstracts and landscapes. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Mulfall also does incredible illustrations using only a ballpoint pen. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

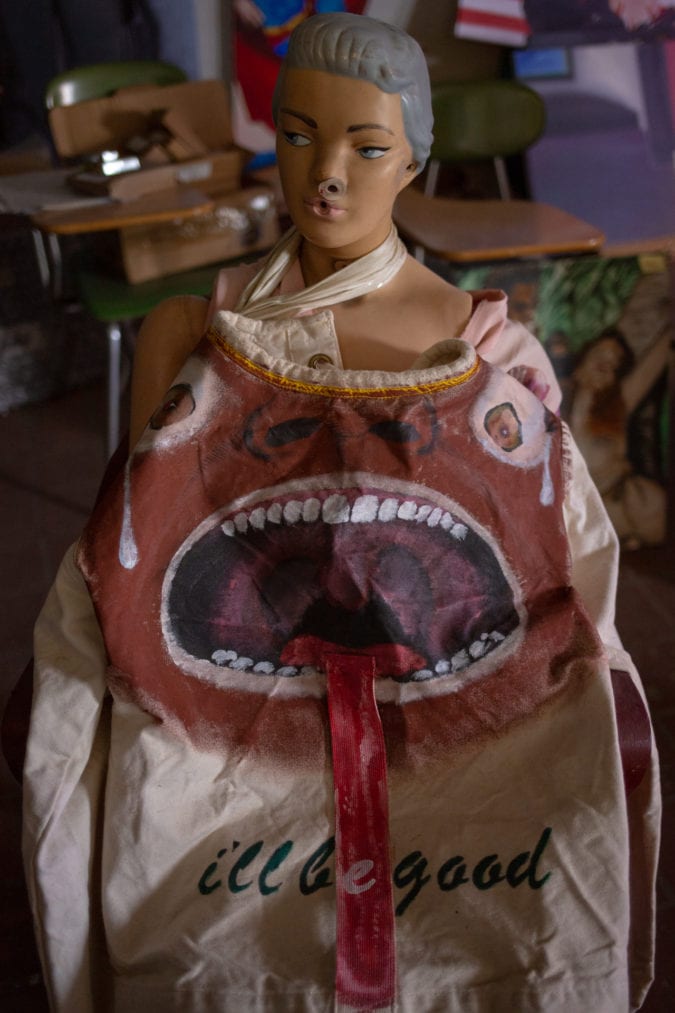

Some of the art produced at the Living Museum could be called folk art, some of it is abstract, and some pieces defy categorization altogether. Some of it is quite dark, while other pieces are more serene.

There are straight jackets, dolls, devils, mannequin parts, and at least two skeletons; but there is also an indoor garden, beautiful portraits, and powerful statements on religion, race, and overcoming trauma. In addition to painters, the museum hosts sculptors, poets, photographers, and musicians.

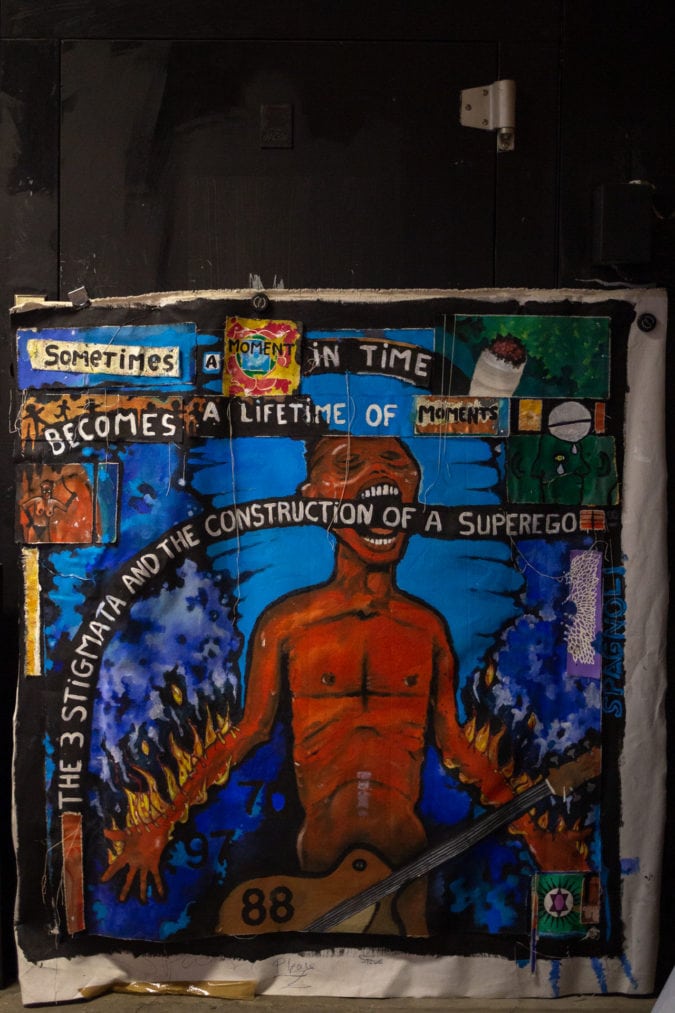

The artists at the Living Museum aren’t immune to the expectations for an art collective made up of artists openly struggling with mental illness. A particularly tortured piece of Spagnoli’s features a screaming, burning figure and the words “Sometimes a moment in time becomes a lifetime of moments.” He laughs as he points to it: “If we sent out a Christmas card, this would be on it,” he says.

“We are more interesting because we are more honest.”

“I want people to have the same experience here as when they go to the Museum of Modern Art, or the Whitney,” Marton says. “I don’t even think there’s a difference. Actually, I think the difference is that we are better. We are more interesting because we are more honest.”

If you go

The Living Museum is open by appointment Monday through Thursday. Tours take place 10 a.m. to noon and 2 to 4:30 p.m. and can be arranged by calling 718-264-3490.