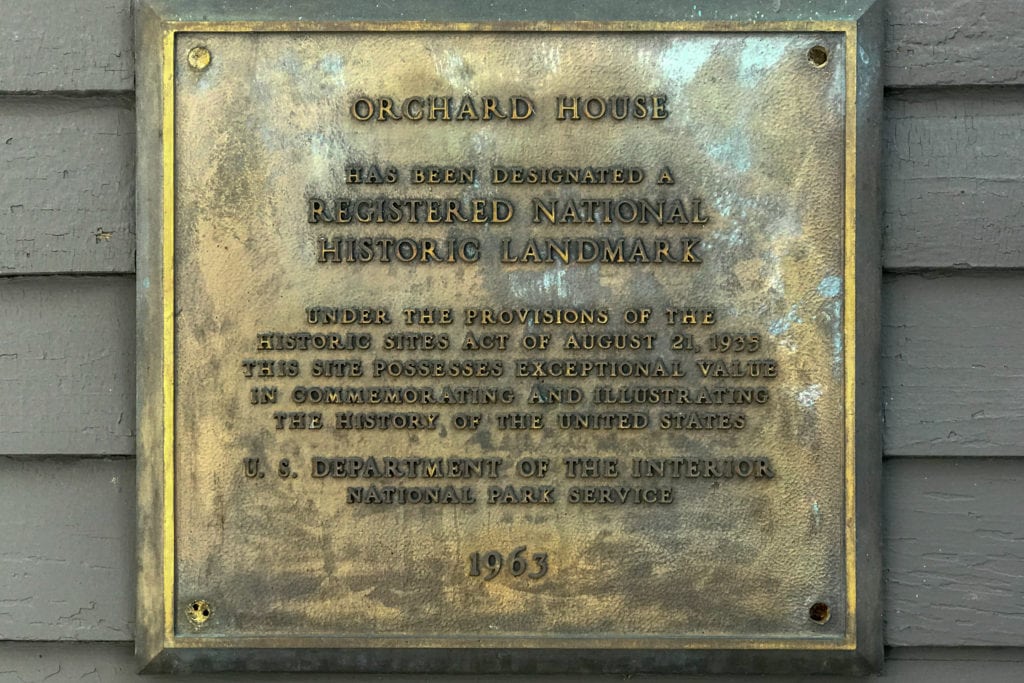

Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House is one of the rare places that exists in both fiction and reality. The former home of the beloved author is located in Concord, Massachusetts, 20 miles northwest of Boston. Alcott both wrote and set her seminal novel Little Women in her family home, which has seen an increase in visitors thanks to a 2018 PBS adaptation and, most recently, Greta Gerwig’s Academy Award nominated 2019 film centered around the fictional March family.

Key Takeaways

- Visitor numbers surge as people worldwide come to Orchard House, drawn by the happy mood created by recent Little Women movies.

- The film team built a nearly perfect copy of Orchard House after many visits to study its rooms and colors.

- The home shows real moments from the Alcotts’ lives, including sickness, art, family loss, and the sisters’ creative play.

Though none of Gerwig’s Little Women was shot in or around Orchard House, Jess Gonchor, the movie’s production designer, made 10 visits to the property. He spent days with Jan Turnquist, the executive director of Orchard House, taking in the home’s dimensions, paint colors, and other design details. “It’s amazing,” Turnquist says. “They made up a perfect replica and I thought it was just beautiful.”

This year, Turnquist estimates that the number of visitors from all over the world has tripled, even during the typically slow winter season. “I think the movie has gotten such a positive reaction that it’s just made a lot of people feel very happy when they come,” Turnquist says. “I mean, the atmosphere in the house is truly joyful. The people who are visiting are smiling.”

Inside Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House in Concord, Massachusetts

Louisa May Alcott’s Bedroom and the Desk Where She Wrote Little Women

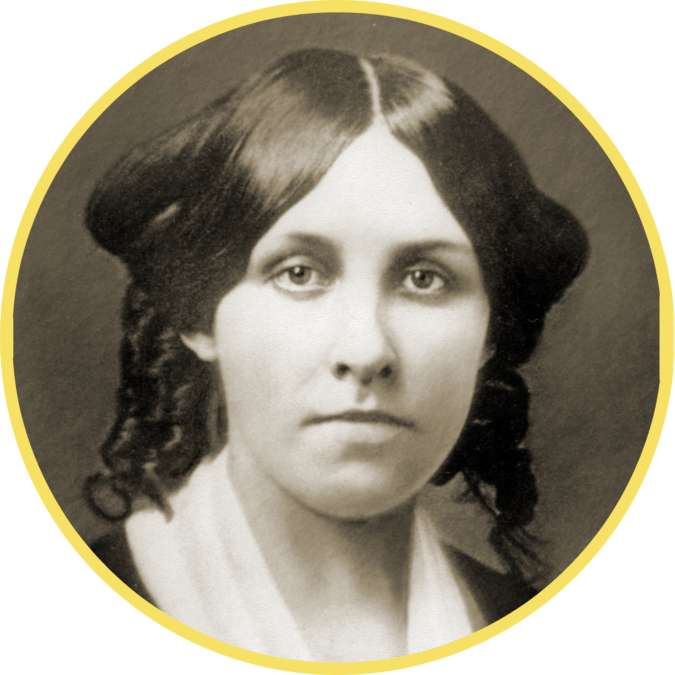

For fans of any adaptation of Little Women, a visit to Orchard House is almost like coming home or checking in on an old friend. The tour of the home begins at the top of the staircase in Alcott’s bedroom. Though she did not move into Orchard House until she was in her 20s, Alcott spent a great deal of time in her bedchamber, particularly after she returned to Concord in 1862, seriously ill after serving as a nurse in the Civil War.

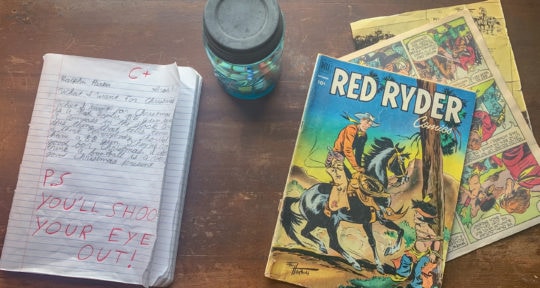

Alcott’s sister May—a famous artist in her own right—painted owls on the walls and mantle of Louisa’s room because they were her favorite bird; she hoped they would bring Louisa comfort and inspiration. The room itself is simply furnished but cozy, featuring a wooden sleigh bed, a wash basin, and embroidery threads and tools. The famous half-moon-shaped desk, where Alcott wrote Little Women in 1868, was built by her father.

Alcott based the character of Jo March on herself, weaving in her own struggles and experiences as a female writer in the 19th century. The three remaining March sisters were inspired by Alcott’s real life siblings, May, Anna, and Lizzie.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

May Alcott’s Artwork, Wall Drawings, and Painting Studio at Orchard House

The next stop on the tour is May’s bedroom, where she was permitted to draw on the walls. Most surfaces in the room, from the window frame to the closet, are covered in drawings of everything from angels to Roman soldiers. Several of her framed paintings hang in the room. Louisa’s parents, Bronson and Abigail Alcott, had a large room across the hall from their daughters’. Today it houses their eldest daughter Anna’s wedding dress, as well as a passageway to the nursery. Anna was married in Orchard House and moved back into the home after her husband died in 1870.

On the ground floor, visitors are guided through May’s painting studio, where the original cast of her foot is on display. Next to the family’s modest kitchen is a dining room that doubles as a gallery for many of May’s paintings, including one that was exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1877. Though Louisa’s sister Lizzie died shortly before the Alcotts moved into Orchard House, her presence looms large in the home; her melodeon still sits in the dining room next to the back staircase.

The front parlor, used for entertaining, features a piano and other musical instruments, as well as board games. This was the room where the Alcott sisters put on plays for family and friends. Bronson’s study is on the other side of the ground floor and stands as a testament to his love of philosophy, literature, and free thinking; numerous bookshelves include titles from great authors, including his own daughter.

Beyond Little Women: Everyday Life of the Alcott Family at Orchard House

Unlike many historical homes that have been preserved to show what life was like for the upper classes, Orchard House provides a glimpse into the everyday lives of an ordinary family. “[The Alcotts] were not in any way wealthy, certainly, and even to call them middle class might have been an exaggeration,” Turnquist says. Rather, she says they were “genteel poor,” meaning that although the family didn’t have money themselves, they did have wealthy relatives who could give them hand-me-downs and access to other resources.

Bronson Alcott’s Progressive Schools and Education Reforms

Though Little Women may be the primary draw to Orchard House, the property also showcases Bronson’s work as a transcendentalist and education reformer. Any money the Alcott family did have went to fund Bronson’s private schools, which Turnquist says were about a century ahead of their time. In addition to refusing to employ corporal punishment and allowing students to ask questions and be active participants in the learning process, Bronson was also the first educator in Boston to permit an African American student to enroll in his class. Refusing to sacrifice his ideals for the chance to remain financially solvent, Bronson saw many of his schools close, losing a lot of money in the process.

The Alcott family moved 20 times before 1857, when Bronson purchased 12 acres of land with a dilapidated manor house on the property for $945. “Orchard House itself was really thrown in for free when the property was bought because it was in horrible condition,” Turnquist says. “Everyone thought it would be torn down, but it was the only thing he could afford. They were really salvaging something that someone else would consider trash.”

Bronson couldn’t bear to tear down the once-grand house, which was built in the 1600s. He spent a year fixing up the house—surrounded by 12 acres of apple orchards—before moving his family into what he named Orchard House. The family received castoffs from wealthy relatives, such as rolls of wallpaper or old carpet, and over the years, Louisa continued to make improvements to the house.

Transcendentalists at Orchard House, from Emerson and Thoreau to Modern Literary Tourists

The Concord School of Philosophy at Orchard House

Leaders of the transcendentalist movement, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, were frequent visitors. Emerson supported Bronson’s idea for the Concord School of Philosophy, one of the first adult education programs in the country. The school, open to anyone who wanted to learn—including women—first met in Bronson’s study in Orchard House, then later moved to a barn-like structure on the property, which still stands today.

“He wanted it to look very rustic, because one of the tenants of the transcendentalist thinking was that nature was the way you find the ‘oversoul,’ and anything that could look more rustic and natural was more suitable for that kind of a gathering,” Turnquist says.

The Alcotts remained in Orchard House until 1877, when Bronson sold it to William Torrey Harris, a fellow philosopher, educator, and co-founder of the Concord School of Philosophy. Harris was unable to spend much time at Orchard House, and the home fell into disrepair. Not wanting to see the home torn down, the Alcott’s next-door neighbor, author Harriett Lothrop, purchased the property. With the help of the Concord Women’s Club, Lothrop founded a house museum which opened to the public in 1911. Anna’s sons donated much of the family’s furniture and belongings back to the museum and today, approximately 80 percent of the furnishings are original to the Alcott family.

Though Orchard House has become a popular destination, Turnquist welcomes the influx in visitors. “Just come with a little bit of flexibility and know that we are delighted to have visitors,” she says. “We just love it.”

If You Go: Planning a Visit to Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House

Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House is open seven days a week year-round. Hours vary by season.