The warmth of Nebraska’s afternoon air and the steady drone of the car’s powerful V8 engine had lulled my exhausted body into a deep, although unsettled, sleep. Jolted awake by a sudden lurch to the left, I inhaled sharply, feeling out of place in the right-hand seat of my own car. My armpits were damp and a sheen of sweat glistened on my forehead.

I’d had a disturbing dream about something having gone wrong with the car. Back in the conscious world, the machine was still hurtling westward on I-80, although its triple-digit speed had been slowed somewhat by a series of thick knots in traffic.

Who were all these people, and why were they all in Western Nebraska?

The sudden movement that had awoken me had come from my co-pilot—Matt Davis, a television station manager from Pittsburgh—as he swerved around a slow-moving truck.

“Mornin’!” he chirped, his gaze locked on the cluster of cars and semi-trailers ahead.

He was dressed like Captain Chaos, Dom DeLuise’s deranged superhero character from the movie Cannonball Run. It’s been his schtick for the past couple of years—a dream come true for a man who said he wanted to portray a fat superhero at Comic-Con. Little did he know when he selected his character that he would soon be behind the wheel of a cream-colored 1974 Oldsmobile sedan, reenacting the event the movie was based on in a modern-day rehash of the Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash.

Behind the Cannonball

If you ask someone what they know about the Cannonball, odds are they’ll have some recollection of a young, mustachioed Burt Reynolds, a becaped Dom DeLuise, Farrah Fawcett, and a crazed doctor character running around in an orange and white ambulance in the 1981 movie Cannonball Run. But the illegal cross-country race that formed the basis of the film—the Cannonball Baker Sea-To-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash—was the real deal.

Brock Yates, the motorsports journalist who came up with the idea, is widely regarded as a legend among his spiritual descendants. Taking note of the fact that no one had claimed a cross-country speed record since 1933, Yates, his teenage son, and a couple of friends decided to make a go of it in 1971. They set a new record from New York City to Los Angeles. A few months later, they made another run, joined by a handful of other racing drivers and motorsports enthusiasts. Another record was set.

The seeds of a movement had been planted. The race was on, so to speak. Yates rallied the troops again in 1972, 1975, and a final time in 1979, with each event spawning new speed records and becoming more boisterous. By the time the last Cannonball was run—consequently, the one the film script is based on—there were nearly 50 vehicles in the field (including a giant, gas-guzzling pickup truck and a couple of motorcycles). Many of them were flashy sports cars. Yates had captured the imaginations of drivers everywhere, but in the process, had also attracted the notice of law enforcement. But at that point, the Cannonball concept had taken on a life of its own.

Yates had captured the imaginations of drivers everywhere, but in the process, had also attracted the notice of law enforcement.

Yates prudently shuttered the loosely-organized, unsanctioned event at the end of that raucous decade, but a couple of spinoffs popped up in the early ’80s. They were met by hard-nosed highway patrol officers eager to discourage further attempts at running a Cannonball. For decades, no one ran an organized Cannonball along those same lines: several teams participating in a no-rules, point-A-to-point-B race, with the only object being lowest elapsed time and the only prize being ego-based glory. But there were still record attempts.

Bringing back the classics

In 2007, Alex Roy—a nightclub owner and chair of The Moth storytelling series, who had made waves with his outsized presence in a number of supercar rallies—broke a 32-hour, 7-minute record set in 1983. The 31-hour, 4-minute time he and his co-pilot posted in a souped-up BMW 5 Series stood for several years. Then in 2013, Ed Bolian, a Lamborghini salesman from Atlanta, destroyed Roy’s record in a modified Mercedes-Benz CL55 AMG coupe. His team set a 28-hour, 50-minute New York-to-LA record that still stands.

But it was Roy’s record run—and a public persona that grated on some—that motivated a small group of friends from the San Francisco Bay area to start their own low-budget New York-to-San Francisco Cannonball—modeled on the 24 Hours of Lemons—called the 2904. That eventually begat a classic car-themed Cannonball called the C2C Express.

Today, there are people who at some undisclosed time each year drive modified (and, sometimes, unmodified) 40-plus-year-old cars as fast as they’ll go across the entire country. It’s the most brazen closing of ranks among scofflaw racers since the ’70s, and it’s gotten mildly competitive. That’s to say nothing of the individual record attempts undertaken every now and again in really fast cars by people whose names are kept on the QT.

Today, there are people who at some undisclosed time each year drive modified 40-plus-year-old cars as fast as they’ll go across the entire country.

How do I know? I’ve run four modern Cannonballs, and won one of the two New York-to-San Francisco races run in 2017 driving a 1974 Oldsmobile Omega sedan I rebuilt and modified in a parking lot in Brooklyn. It’s thrilling to drive as fast as you can for hours on end in a machine you prepared yourself, and it’s an addiction shared among people who get more out of shaving hours off of travel time than they do taking in the sights.

What it’s like to Cannonball

There has been a resurgence of proper group Cannonball runs over the past decade, although the cars participants drive are much less expensive than the top-of-the-line-for-the-seventies machines that careened from coast to coast when wide, polyester lapels and fat ties were still in vogue.

“If you told me a year ago that I’d be doing this, I wouldn’t have believed you,” Matt Davis said again and again throughout our 36-hour, 7-minute drive across the United States. We had been introduced through mutual friends, and had met in person only a couple of days earlier when he showed up in Brooklyn to help me make last-minute preparations. Like so many of us, he was living out a childhood fantasy. At times, when we weren’t trying to scrunch our minds around the fact that we were still sitting in the car after so many hours, the trip was exhilarating.

As Davis guided the car further westward across the tan flatness of the prairie, I stared ahead, bleary-eyed and slack-jawed, and adjusted my pillow against the passenger-side door. I needed more sleep before it was my turn to drive again. I’d driven more than 1,000 miles at the beginning of the trip—a third of the distance across the continent—stopping only once for fuel before relinquishing the driver’s seat at our second fuel stop in Davenport, Iowa. With an extra fuel tank in the trunk, we were able to carry more than 50 gallons of fuel, boosting our range between fill-ups to several hundred miles.

Although we had intended to start much earlier than we had, we didn’t end up leaving New York City until after 10 p.m. (I’d really wanted a veal parmigiana sandwich from a particular Italian restaurant in Brooklyn before we took off, which had led to a significant delay.) The upside was that there hadn’t been much traffic when we departed. We were out of Manhattan and barrelling across New Jersey and Pennsylvania in no time. It was nighttime and the roads were clear, so we made good time. But here we were, plodding through traffic in Nebraska of all places, watching our average speed numbers suffer. We still had half the country to go, though, and I hoped we could make up for the delay later in our journey.

I nodded off again, slipping into a dream in which I was checking over the car. Oil level? Check. Tire pressure? Check. Windshield cleaned? Check. The mechanical stuff seemed okay, but something was off. In the dream, I became detached from my body, floating above myself, voiceless and bodiless, like a freshly departed soul. I tried to scream, to wake myself, but could no longer make a sound. My body, with its vocal cords and voice, was lying beneath me, motionless as the minutes ticked by.

Get up! Get up and drive!

Again I snapped awake, only to find Davis still at the wheel, driving the car hard toward the Pacific Ocean. He’d found an opening.

I had spent countless hours preparing the car on that lonely patch of crumbling asphalt near the Brooklyn waterfront. It was a $700 Craigslist find, and over the previous two years, I had changed the engine—twice—rebuilt the suspension, and beefed up the brakes. My wife was only mildly satisfied that my mistress wasn’t another woman. It was that car—it was the race. She hadn’t seen much of me for weeks.

The clock was ticking, but our forward progress—and therefore our ever-important average speed—was still intact. Satisfied that we were still in good shape, I drifted back to sleep. It wasn’t long before I awoke again, anxious thoughts galloping through my tired, confused mind for a minute or two. I was a skilled, safe driver and so was my co-pilot, but statistically, driving fast increased the odds that someone could get hurt or killed. In the passenger seat, I felt helpless as the car hurtled through time and space like a terrestrial rocket.

Keeping the average speed as high as possible without wasting fuel was key, but so many things can trip you up along 2,900-plus miles. Traffic, accidents, weather, driver fatigue, even payment problems at the fuel pump could dig into our overall elapsed time. So we kept the car going as quickly as was prudent, trying always to keep our delays to a minimum. Elapsed time—the time it took to drive from the Red Ball parking garage on the east side of Manhattan to Coit Tower in San Francisco—was everything.

Motorized pioneers

Despite growing evidence that our roads and bridges are falling into severe disrepair, most of us take it for granted that you can just hop into a car and drive from New York to California in a few days. It wasn’t always that way—but since the advent of paved highways, there has existed a subset of maniacs eager to prove that the whole trip can be blazed through, in one go, in not much longer than a day.

Since the advent of paved highways, there has existed a subset of maniacs eager to prove that the whole trip can be blazed through, in one go, in not much longer than a day.

Drivers have been trying to set speed records across the continental United States since there have been roads good enough to do it on, and even before then. In 1919, it took then-Lt. Col. Dwight Eisenhower and a squadron of army trucks 56 days to travel from New York to San Francisco across several thousand miles of local roads, muddy tracks, and grueling terrain. The Lincoln Highway, one of the first transcontinental routes, had been established in 1913. But it was little more than a meandering route then; a rough collection of dirt roads and local highways strung together to form a pathway along the Manifest Destiny trajectory.

As a structure, the Lincoln Highway didn’t much resemble a modern highway system. Today, we can count on thousands of miles of continuous asphalt ribboning its way back and forth, up and down, making it possible to drive from one end of the country to the other without stopping for any reason other than to pick up junk food and fuel.

Back then, roads were much more rustic. Yet, even under less-than-ideal road conditions, a trip on the Lincoln Highway was still probably quicker than taking passage through the Panama Canal on an oceangoing steamer. And it was much less dangerous than the wagon routes taken by westbound settlers only a few decades earlier. Still, most people who wanted to cross the United States a century ago boarded a train. The sensible ones did, anyway. But there were always the adventurers.

Most people who wanted to cross the United States a century ago boarded a train. The sensible ones did, anyway. But there were always the adventurers.

The Lincoln Highway wasn’t the only long distance route available in the early days of automobile travel. During the first half of the 20th century, numbered highways were informally organized into auto trails to help motorists navigate point-to-point routes: the Atlantic Highway from Maine to Florida; the Dixie Highway from Chicago to Miami; the Arrowhead Trail from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles; the Old Spanish Trail from St. Augustine, Florida to San Diego. And so on.

The advent of road trip culture

Highway travel got serious during the postwar boom years when Eisenhower, having been promoted by the American public from army officer to president, helped push through the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, effectively creating the Interstate Highway system. That legislation set in motion a construction bonanza that transformed the continental United States from a patchwork of villages into the strip mall superpower it is today.

Big rig trucks grew larger and more powerful along with Detroit’s flashy new chrome-decked passenger cars and trucks. Better roads and bigger, faster cars shortened distances and increased comfort. Relative to the pre-Interstate era, it became possible to compress time and space, pulling American communities closer together.

As automobiles became less expensive and more reliable in the years following World War I, Americans fell in love with road trips, and with the machines that made them possible. According to the federal Bureau of Transportation Statistics, more than 74 million cars, trucks, buses, and motorcycles plied American Interstates by 1960—up by nearly 25 million registrations from a decade earlier. By 2006, that number had surpassed 250 million.

Double nickel rebellion

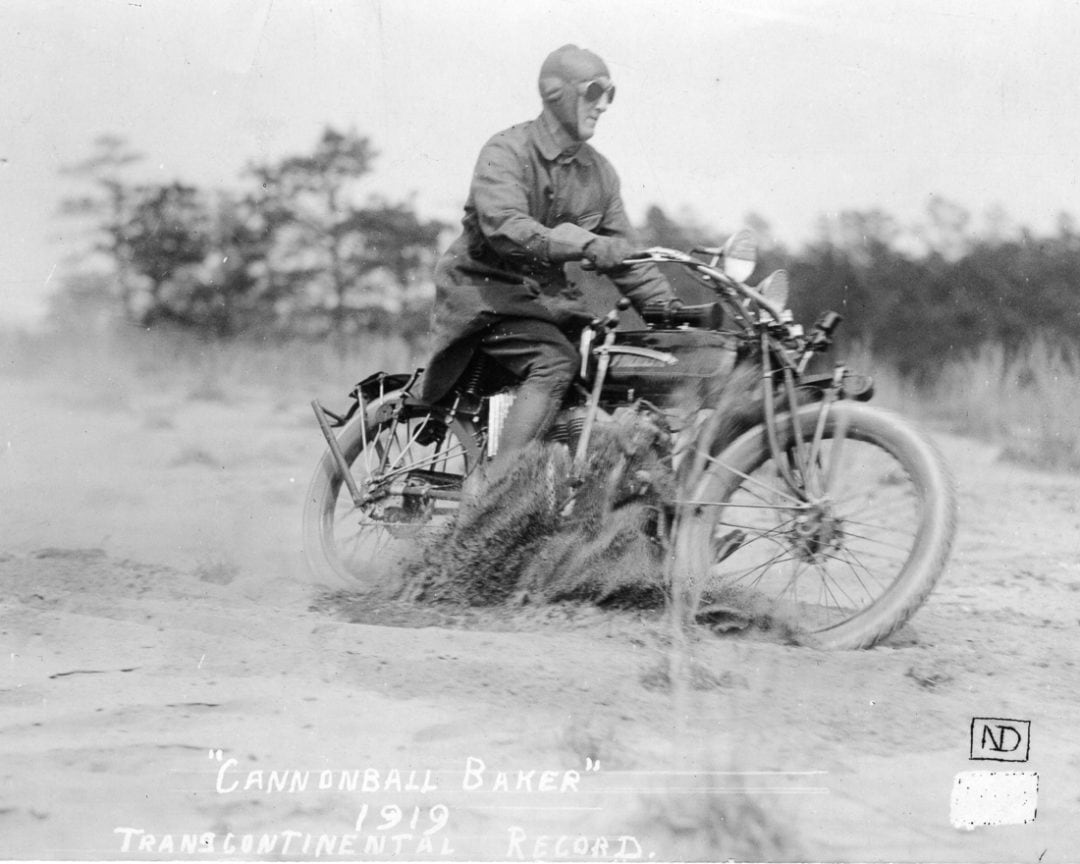

If Brock Yates looms large as the godfather of scofflaw rallies, the granddaddy of the cross-country speed records is Erwin “Cannonball” Baker. A daredevil often backed by auto and motorcycle manufacturers eager to showcase the capability of their latest machinery, he set numerous records in cars and on motorcycles. But his 1933 New York-to-Los Angeles run, which he completed in 53 and a half hours in a Graham-Paige model 57 Blue Streak 8, stood for nearly four decades before someone thought to challenge it. “The record just sort of laid dormant—no one thought about it,” Brock Yates Jr. says. “Brock (Sr.) pulled it out of thin air—he thought it would be fun.”

Yates, who wrote and sometimes served as an editor for Car and Driver magazine, described his motivation to try for a cross-country record this way:

“Why the hell not run a race across the United States? A balls-out, shoot-the-moon, screw-the-establishment rumble from New York to Los Angeles to prove what we had been harping about for years—that good drivers in good automobiles could employ the American interstate system the same way the Germans were using their autobahns … The early ’70s was a time when illegal acts were in style … Everybody was paranoid about everything. What better time to add to the national psychosis?”

So in May of 1971, Yates, his then-14-year-old son Brock Jr., his friend Jim Williams, and Steve Smith, an editor at Car and Driver, got into a souped-up Dodge van they’d dubbed Moon Trash II and headed west to get the lay of the land. Both roads and automobiles had improved markedly since Baker had set his last record, and the Yates team was able to drive from the Red Ball parking garage to the Portofino Inn in Redondo Beach in 40 hours and 51 minutes, setting a new record. “Seeing the country go by looking through the windshield is just an amazing thing,” the younger Yates recalls, pointing out that even then, American highways seemed relatively empty.

The Cannonball became a big middle finger to the hated “double nickel” regulation.

Yates Sr. organized another run only six months later, and was joined by a small group of professional and semi-professional motorsports drivers. The seeds of an almost cult-like movement had been planted.

When the federal government imposed a nationwide 55-mph speed limit following the 1973 oil crisis, the Cannonball became—aside from the more or less hedonistic driving exploit that it was—a big middle finger to the hated “double nickel” regulation, and in Yates’ libertarian mind, to regulation in general.

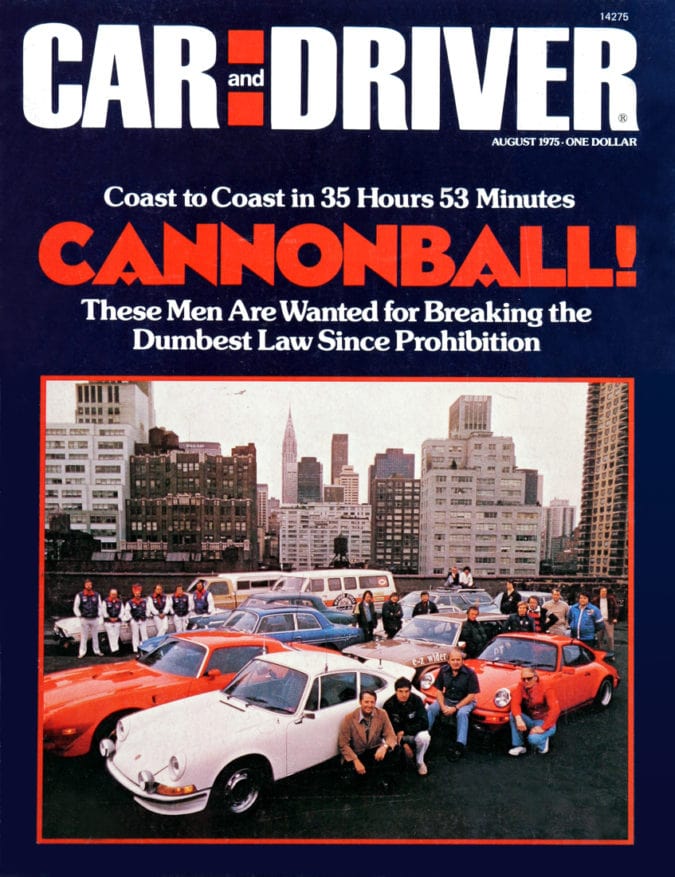

Gero Hoschek, who is working on an in-depth documentary about the Cannonball, says that, according to his research, there was plenty of fuel to go around, and that the speed limit was—as are most cure-alls—a poor solution to an administrative problem. On the cover of its August 1975 issue, Car and Driver called it “the dumbest law since Prohibition.”

“When the energy crisis vanished, the ‘speed kills’ mantra was added to uphold the double nickel, and repeated so often since then that only few remained lucid enough to question it,” says Hoschek.

The Cannonball legend grew throughout the decade, prodded along by Yates’ coverage of it in Car and Driver magazine and a Cannonball-themed newsletter he’d begun publishing. By 1979, Cannonballing had mutated from a seditious whisper into almost open rebellion against traffic law and the authorities who enforced it. The race started at a suburban shopping mall in Darien, Connecticut that year, in front of a motorsports- and hunting-themed restaurant called the Lock, Stock and Barrel. A huge crowd turned out to watch cars leave every few minutes.

“A marching band showed up for a start that was supposed to be secret,” John Harrison, who drove in that year’s event, says. “But it was pretty subdued compared to LA. Once we got there, we partied for a week straight.”

Who are the Cannonballers?

There must be a gene some people have that makes driving across the United States as fast as possible with as few stops as possible, carrying as much fuel as possible (to enable fewer stops), seem like a good idea. When I tell someone I’ve done it—not once, but several times—they often look at me like I have three heads.

“New York to LA in less than 40 hours, that’s insane!” they’ll say.

Those who are amused to hear stories about such exploits are almost never interested in partaking in it themselves. But you do get the odd person who thinks it’s a good idea.

“I saw Cannonball Run and have always wanted to do that!” these others will say.

Roy says its irresistibility is tied into the American myth. “California is the finish line of the world,” he says. “That may sound a little America-centric, but anytime people come to the U.S., they want to drive across the country.”

And that’s how a person’s transformation from Burt Reynolds aficionado to full-on Cannonballer begins. Endowed with the reckless gene, this person will see the movie or read about the actual race, then hear about other reckless people who participate in this madness year after year, then get involved themselves. They’ll often fantasize about winning, or, better yet, setting an elapsed time record. Most obsess over the ideal car to run.

Just ask Alex Roy, Ed Bolian, or Arne Toman, all of whom have spent untold hours and plenty of money preparing—mechanically, mentally, and physically—for the onslaught of nonstop cross-country driving. All of them set records—Roy the first of the new millennium, followed by Bolian with the record that still stands. Toman snagged the New York-to-San Francisco record a couple of years ago.

“Driving at speed is crazy. It caters to adrenaline junkies and people who think too highly of themselves.”

“Driving at speed is crazy,” Bolian says. “It caters to adrenaline junkies and people who think too highly of themselves. We all have that in common, but Cannonballers are generally not rich, evaluate cons differently than other racers, and cling to an idealism that is unique from on-track pursuits.”

America’s finish line

Captain Chaos and I had finally escaped Nebraska’s inexplicable traffic jam. As the sun began its descent over the horizon west of Pine Bluff, Wyoming, I slid back into the driver’s seat of the thoroughly-used Omega. I was feeling refreshed from my nap, and the prospect of driving on empty roads all night had me firing on all eight, so to speak.

Wyoming slipped by, then Utah. The later hours of the night and the earliest of morning blew away with the slipstream as the car screamed through the great American desert. Other than a maverick big rig now and again, scarcely another motorist was to be seen. If we did spot one, the sighting was brief, the lights receding quickly into the rear view.

The lights of Reno loomed into view, signaling the beginning of the end of our journey. Elevated casino neon lights blinked into the night sky for the benefit of only a handful of uncaring passersby. We began our descent out of the Sierra Nevada mountains, slowing down briefly for a California agricultural inspection station that wasn’t yet open as we thundered toward the coast. For an hour or two, it looked like we might slip into the San Francisco Bay area before the Monday morning rush. Bleary but alert, we perked up, charged up that we might actually be in the 34-hour range. Thirty-four hours to San Francisco!

But as the roadway segued from exciting downhill sweepers into the kind of big, soul-crushing commuter freeway that almost always fills to the brim, a wall of red lights ahead spelled out our reality. A last ditch effort to bob and weave through the quickly-closing gaps in traffic and evade the rising tide of gridlock was fruitless. The last 30 miles of the trip took two hours, and our average speed fell considerably. The grim daily struggle for thousands of Bay Area commuters pummeled our 34-hour dream beyond recognition.

A last ditch effort to bob and weave through the quickly-closing gaps in traffic and evade the rising tide of gridlock was fruitless.

When we finally reached Coit Tower, it was only after sitting helpless in front of red light after red light. Even if we’d wanted to flout order and authority and blow through the lights, there would have been nowhere to go. The red light wall had coagulated into an impenetrable fortress of congestion. The veal sandwich, tasty as it was, had been a poor life choice.

A little dejected by last-minute futility, we crunched the numbers, adjusting for time zone change. Our spirits were buoyed when we saw what we’d achieved. Thirty-six hours and seven minutes—not too shabby. We were hours behind Toman and one or two of the other entries running newer, more aerodynamic cars in a different, albeit concurrently-run race. But considering traffic, and the limitations of our anachronistic equipment, we’d done alright.

It wasn’t until later that we learned we’d beaten all the entries in the classic car race and even most of the newer cars in the other race. Our main contender—a three-man team in a race shop-prepared ’77 Chevrolet Monte Carlo—had dropped out of the race somewhere in Indiana, victims of transmission failure.

Returning to reality

At the end of every race, there’s always a little celebration. Not the week-long benders they had back in the ’70s, but enough time to get to know better the people you spend only a few hours with every year or two—at the beginning and end of every race. Stories are shared, harrowing moments recounted. But it’s not long before more pressing quotidian needs close-in. Reality strips away the shimmery glow left by driving fast toward the golden land. Those who live in the west stay put. They return to their families and go to work. Everyone else trickles back to their respective home turfs as best they know how.

The practical ones sell their cars in situ; the well-heeled have them shipped back to Chicago and Atlanta and Cleveland, or wherever they need to be disposed of. Then there are those of us who drive back, hoping to take a slower, more studied approach to the trip than the sort of mad-dash westward explosion that made America what it is, and which compelled us to try to reach the finish line first.

After our success, my Captain Chaos-impersonating friend boarded a flight back to Pittsburgh. I got behind the wheel again, plodding back across the Southwestern desert and the Deep South in a trip that was the antithesis of Manifest Destiny. It was a slow, reflective, almost aimless journey.

I listened to Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire on audiobook as I drove across a country deeply divided by differences in culture and economics. Was I looking for the fissures in our giant, speedy nation? No—even though Gibbon’s narrative did seem relevant to modern times. I was still basking in the shared spirit of adventure that had prompted a handful of crazies to blaze across North America in a sort of tribute to all those who came before us.