It’s been said that behind every fortune, there’s a crime. And one could argue that truism applies to the national parks and nature preserves in the U.S., all of which occupy land forcibly taken from Native Americans.

Next time you visit a national park, take time to learn and honor its Indigenous history

In recent years, the U.S. has begun to acknowledge the harm done to Native Americans by turning some of their homelands and sacred places into recreation areas for other people. As a result of this belated awareness, the National Park Service (NPS) and the Department of the Interior are working to address some of these wrongs. In 2022, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American to hold that position, issued an executive order that prioritized co-management with local tribes of public lands and resources. As a result of this policy, tribal authorities now oversee some bison herds in Montana and fish hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest.

In some national parks, tribes now co-manage or are formally engaged in decisions regarding the lands they once controlled. In many parks, local Indigenous people’s culture and history are placed front and center, allowing visitors to understand the complete history of the land and the loss suffered by displaced tribes.

Learn about Indigenous history at these National Park Service sites

Here are some national parks that do a notable job of honoring local Indigenous people and their culture.

Glacier National Park, Montana

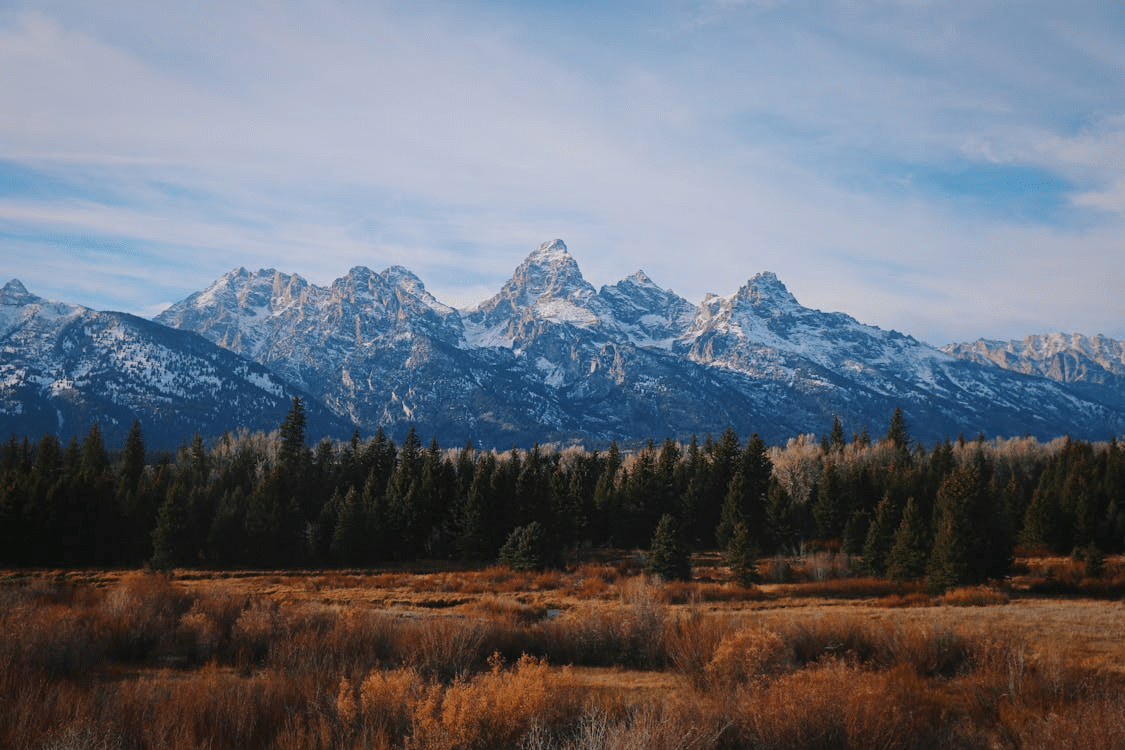

The origin of Glacier National Park is typically problematic. Humans had occupied this stunning rugged terrain for 10,000 years when white explorers and settlers showed up. Its mountains were the center of the universe to the native Blackfeet Nation. When the U.S. government bought the land from the Blackfeet in 1895, it promised that the tribe would retain its right to hunt and gather in the area. But with the creation of the national park in 1910, the Blackfeet were effectively excluded from their homeland.

In recent decades, the long-tense relations between the NPS, the Blackfeet Nation, and other local tribes have improved. Each summer since 1982, Blackfeet, Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreille tribal members have shared their history and culture via the Native America Speaks program, the longest-running Indigenous speaker series in the National Park Service. The program offers presentations at campgrounds, lodges, and other locations across the sprawling park and features storytelling, singing, and hands-on demonstrations.

7 activities beyond the borders of Glacier National Park

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Seashore, Michigan

This popular Michigan park’s name comes from a myth of the Anishinaabek people, including the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi tribes. The park’s location has been an essential resource for humans since at least 11,000 B.C. when it was a popular hunting and fishing area rimmed by glaciers. Artifacts indicate that the area’s Indigenous people traded and interacted with tribes as far away as the Gulf Coast.

The NPS has publicly committed to honoring Sleeping Bear’s Native American heritage and partner with the local tribes. This includes having tribe members train park staff on Indigenous history and issues, hiring tribal youth for jobs in the park, consulting the tribes on interpretive signage, and incorporating Indigenous knowledge into the park’s social media and digital content. Opportunities to learn about the local Indigenous people and their culture are woven into the park’s programs, scenic trails, and other recreational activities.

Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia

Last year, the Rappahannock Tribe re-acquired 465 acres at Fones Cliffs, a sacred site on the Rappahannock River inside the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge in Virginia. The Rappahannock Tribe lived in villages in the cliffs area before English settlers arrived. It was here they first met and fought with those settlers in 1608.

The cliffs, purchased with money from various foundations, will be open to the public and co-managed by the Rappahannock and the Fish and Wildlife Service. The area is essential to several species of birds, including bald eagles, which nest there in large numbers.

The Rappahannock plan to create trails and a 16th-century replica village where tribe members can educate the public about their history and Indigenous approaches to conservation. The land will also allow the tribe to expand its Return to the River program, which introduces tribal youth to traditional river knowledge and provides education for other communities interested in the Rappahannock River.

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska

Indigenous people lived in the area now occupied by Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve for several millennia before being displaced by a surge of glaciers some 250 years ago.

Descendants of those displaced residents, now known as Huna Tlingit, still consider the park’s location their homeland. The tribe has worked with the NPS to build Xunaa Shuká Hít, a tribal gathering house that also serves as a cultural center where visitors can learn about the area’s Indigenous history and traditions.

A 150-acre cultural site on land acquired with assistance from the National Park Foundation and The Conservation Fund is managed in collaboration with the tribal government, the Hoonah Indian Association. It allows tribal members to engage in traditional cultural practices while expanding the park’s fishing, hiking, and camping options.

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, Hawai’i

This breathtaking park protects and shares two things: volcanoes and native Hawaiian traditions. The park’s Cultural Resource Preservation is an ongoing effort to celebrate Hawaiian culture, from native crafts and building methods to food, language, and place names, through live demonstrations and online videos.

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park is also one endpoint of the Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail. This 175-mile shoreline corridor protects and provides access to a network of culturally and historically significant trails. The “trail by the sea” passes through some 200 traditional Hawaiian land divisions filled with important Hawaiian sites and gorgeous natural scenery.