When I visit the Newseum in late December, it’s a gray day in Washington, D.C. Clouds hang low over Pennsylvania Avenue, rendering the sky nearly the same shade of off-white as the Capitol’s ornate iron dome. In the photos I take from the museum’s outdoor terrace, the seat of the legislative branch almost disappears and I try not to see it as an omen. Just two days before my visit, Donald Trump has been impeached by the House of Representatives and our democracy feels as precarious as ever.

It can be easy to get overwhelmed with the never-ending, modern 24-hour news cycle, but there are still moments—both good and bad—that feel historic, even as we are still experiencing them in the present. When we recall similar moments from our collective past, quite often the images that come to mind are headlines, whether or not we were alive to see them in print: “Dewey Defeats Truman,” “Man Walks on the Moon,” “America Attacked,” or “Yep, I’m Gay.”

When we recall similar moments from our collective past, quite often the images that come to mind are headlines, whether or not we were alive to see them in print.

In 2008, print copies of those front pages and other news-related artifacts were put on display half a mile from the Capitol at the Newseum, with the stated mission to “increase public understanding of the importance of a free press and the First Amendment.” The museum encourages visitors to “experience the story of news, the role of a free press in major events in history, and how the core freedoms of the First Amendment—religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition—apply to their lives,” according to its mission statement.

Although the museum attracted nearly nearly 10 million visitors in just over a decade, it struggled financially, and—11 years after it opened—the Newseum will close for good on December 31. The museum’s building has already been sold to Johns Hopkins University, and the artifacts on display will be moved offsite and continue to circulate around the country.

-

A view of the Capitol. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The museum’s entrance. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The Today’s Front Pages display. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The outside of the Newseum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A terrace inside the museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The inside of the museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

An imperfect museum

After the Newseum closes, the group behind its creation, the Freedom Forum, will continue its mission to champion the First Amendment through educational efforts in public and online. But the closing of the Newseum still feels like a loss—to news junkies, international tourists, and all people guaranteed rights by the U.S. Constitution.

The Newseum is not a perfect museum, and critics haven’t been shy in their “told-you-so” critiques since its closure was announced. In a city where most of the world-class museums are free, the Newseum’s $25 admission price is a bold ask. While some of the exhibits make sense—physical copies of newspapers and other print ephemera—others are a bit of a stretch. I can’t say I didn’t enjoy the “fetching facts” (and accompanying photographs) in the First Dogs: American Presidents and Their Pets exhibit, but I struggle to see the connection between good boy Bo Obama and our freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, or petition.

One could argue that almost anything deemed newsworthy at one time has earned a place in the Newseum, a parameter that is nearly limitless. But it’s one thing to display an object or commemorate a tragedy—where the Newseum succeeds, it does so in conveying how a particular moment in history was captured by, and portrayed in the press.

The 9/11 Gallery showcases the crucial role of a free press better than any of the museum’s other exhibits, with videos, a wall of front pages, and a twisted section of the 360-foot antenna mast that fell along with the World Trade Center’s North Tower. In an 11-minute video, “Running Toward Danger,” journalists tell their heart-wrenching first-hand accounts of the tragedy. A separate video highlights photojournalist Bill Biggart, who snapped photos up until the moment he was killed by debris. The sound of people sniffling and the presence of tissue boxes outside of the theater prove that it’s not just journalists who sometimes struggle to balance their objectivity with their humanity.

500 years of history

The museum’s building is somewhat confusing to navigate; seven levels of glass and steel, full of terraces, narrow walkways, and staircases that sometimes lead to nowhere. Quotes are a foundation of journalism, and here they’re everywhere: projected onto a huge screen in the lobby, carved into the walls, and on tiles set into the restroom walls. A quote by civil rights activist and politician Julian Bond reminds visitors that freedom of the press is just one of five freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment: “Any time someone carries a picket sign in front of the White House, that is the First Amendment in action.”

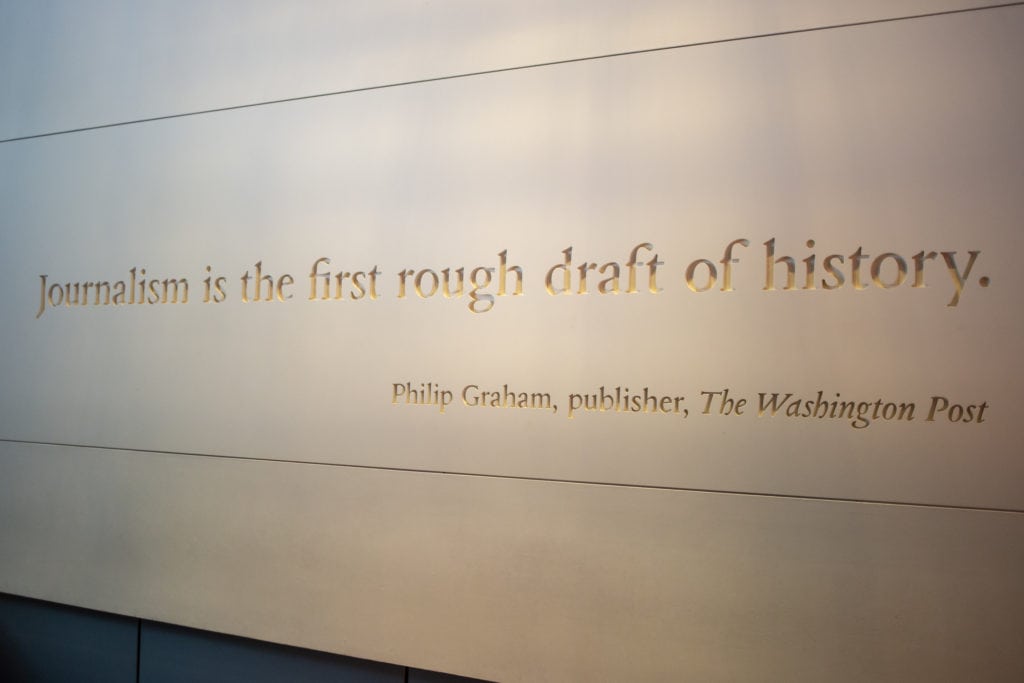

The 8,000-square-foot News History Gallery is the largest of the museum’s 15 galleries. A central “spine” contains three levels of pullout drawers featuring 400 print newspapers, magazines, and newsbooks, collectively covering more than 500 years of history. It’s here that I first see front pages announcing Nixon’s resignation, Elvis’ death, Billie Jean King’s “Battle of the Sexes” victory over Bobby Riggs, and the Challenger explosion. All of these events happened before I was born, but as Philip Graham, one-time publisher of the Washington Post said, “Journalism is the first rough draft of history.”

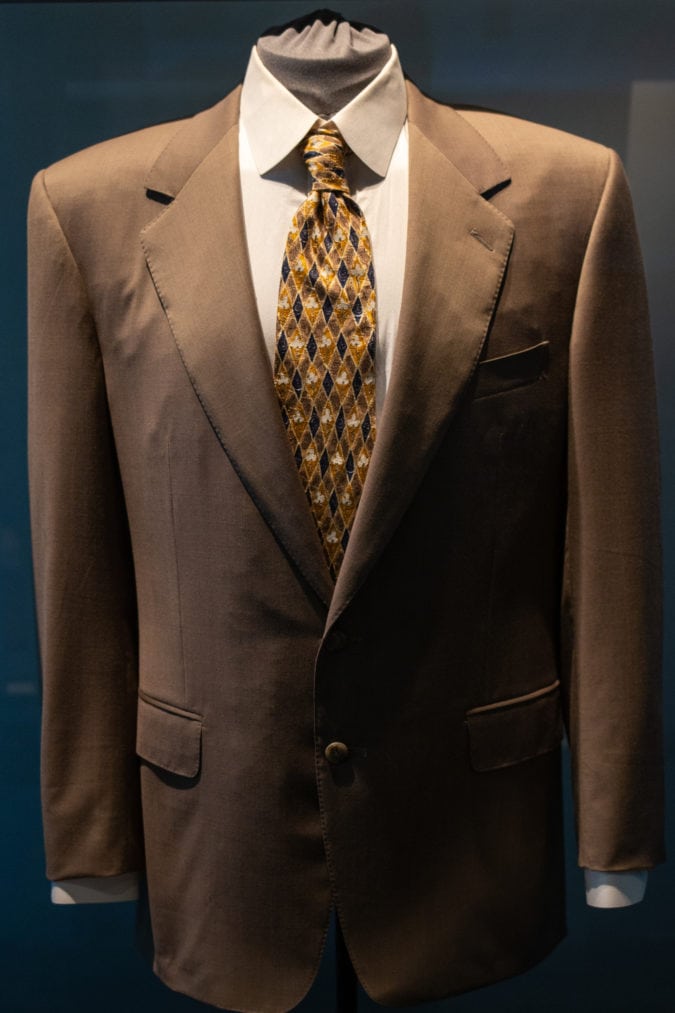

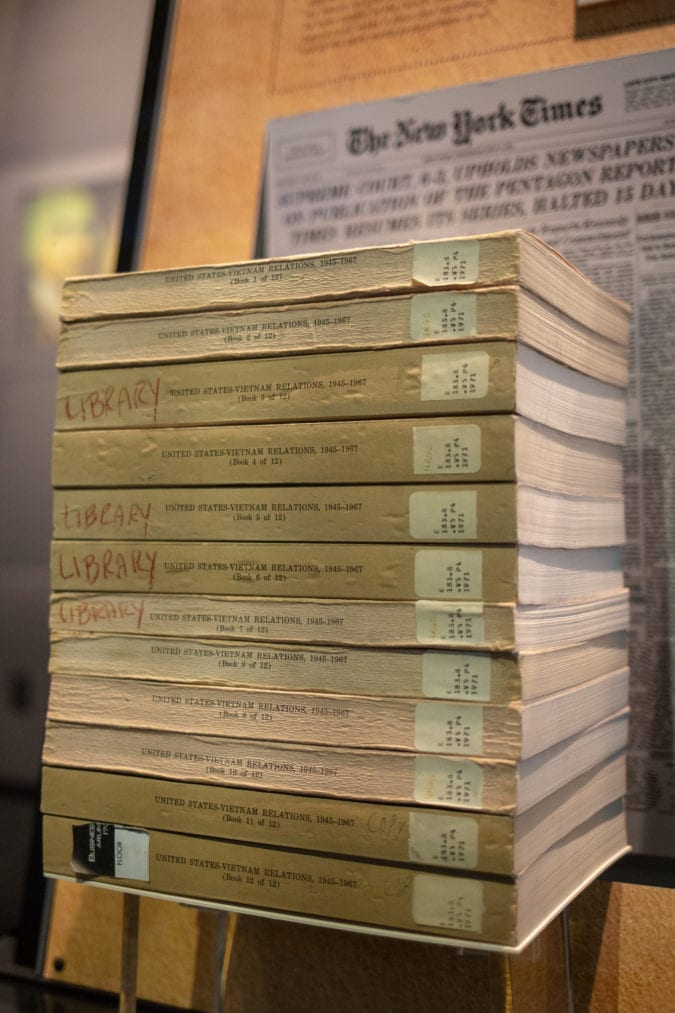

Cases containing artifacts line the walls of the gallery, and include a stack of bound Pentagon Papers, the door from the Democratic National Committee’s Watergate headquarters, a voting machine from Florida used in the 2000 presidential election, the jacket and tie worn by O.J. Simpson in court, Nellie Bly’s satchel, and a red dress worn by White House Press Corps legend Helen Thomas. Another gallery features a three-story East German guard tower and eight 12-foot-high concrete sections of the original Berlin wall, the largest such display outside of Germany.

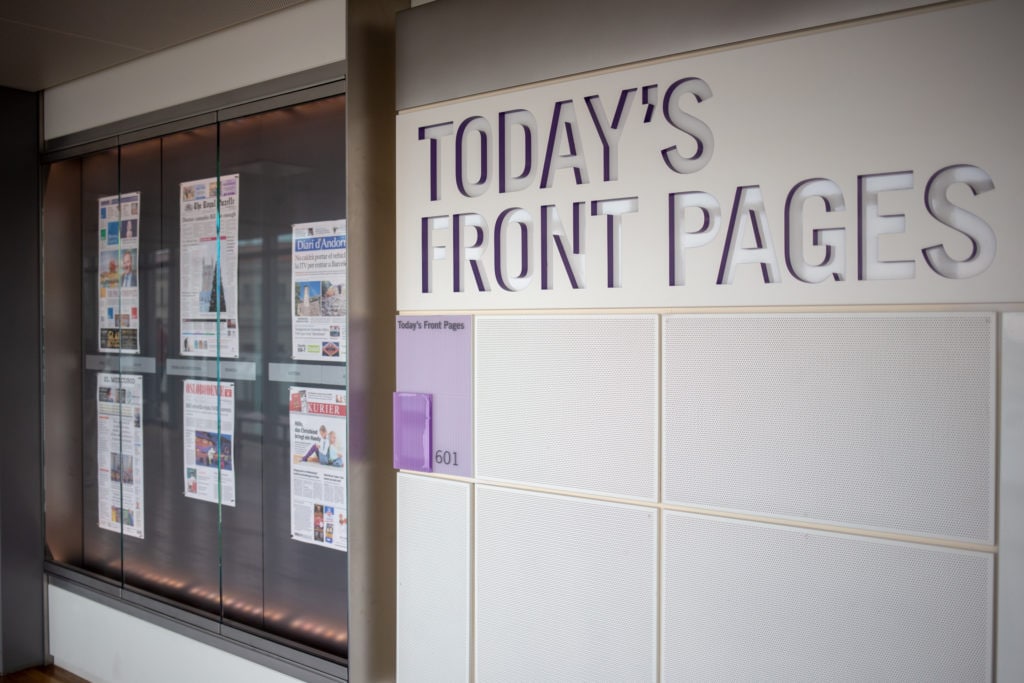

Lining the sidewalk in front of the museum’s entrance are cases containing printed copies of each day’s front pages from newspapers around the country. The Today’s Front Pages exhibit continues inside and includes international editions. This is a fascinating look at the way news is covered (or not covered)—and thankfully the online version will continue after the museum closes.

-

The west side of the Berlin Wall. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The “spine” containing print materials. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

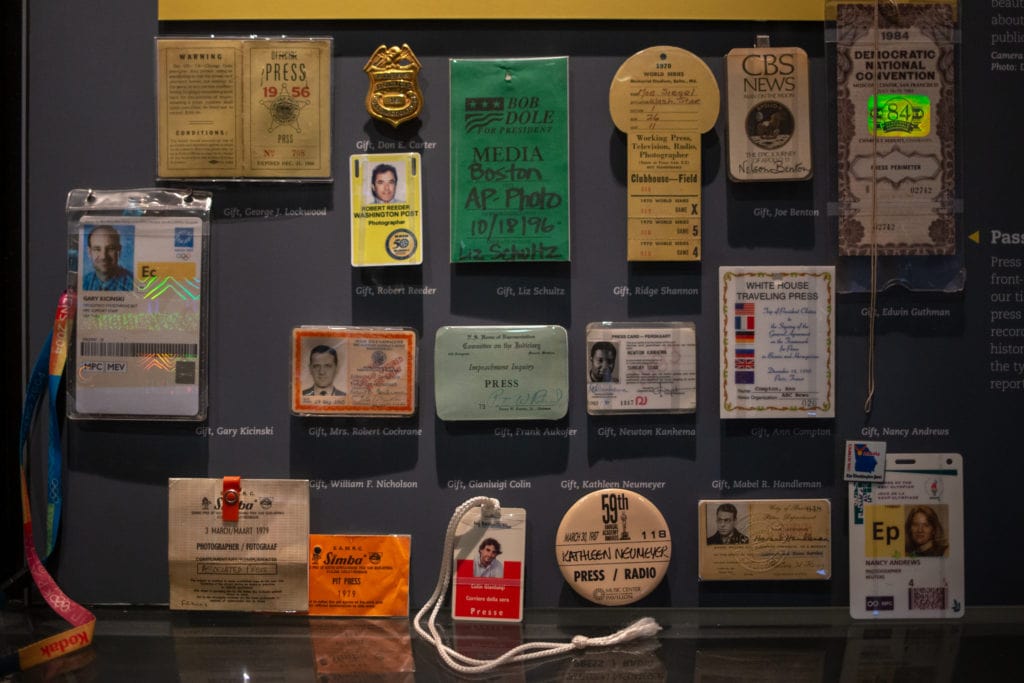

A collection of press passes. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

International front pages. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

An outdoor terrace overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

One of the many quotes displayed all over the museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The future of freedom

The Newseum as a whole is a physical love letter to the First Amendment, the words of which are inscribed into the building’s patchwork facade. A red-white-and-blue banner further explains that “The Newseum Celebrates our First Amendment Freedoms,” an add-on that seems to suggest that the museum, much like the press itself, has at times struggled to convince visitors of its purpose and inherent value.

It’s easy to draw grim parallels between the current state of the world and the closing of a museum dedicated to our most precious of freedoms. The exhibits of the Newseum largely remain objective, so it’s left to the visitor to interpret current-day events through the lens of history. But while it’s true that print journalism has been declared “dead” or “dying” since the early 1990s (a Time Magazine cover heralding “The Strange New World of the Internet” is part of the museum’s collection), we still crave physical reminders of historic events.

On the day after the impeachment vote, stacks of newspapers for sale in New York’s Penn Station were uncharacteristically low, and in some cases completely empty early into the morning commute. Future headline-making events will no longer have a physical home on Pennsylvania Avenue and as I exit the Newseum, a quote by Thomas Jefferson reminds me why that matters: “The only security of all is in a free press.”