When I first arrive at the Old Idaho Penitentiary, located in the state’s capital, Boise, I’m immediately struck by how beautiful it is. The crumbling stone buildings still have a certain elegance to them, similar to more famous ruins found in ancient cities around the world. What remains of the former prison is drenched in summer sunlight, and surrounded by pink, magenta, and fuchsia flowers, many of which can be traced back to gardens that were tended by prisoners half a century ago.

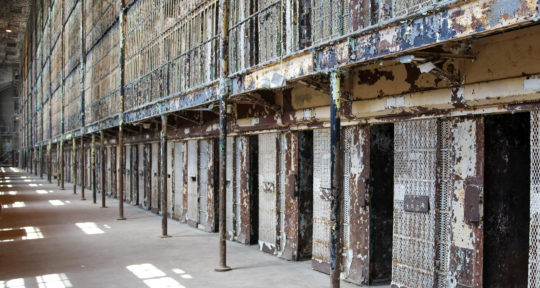

When the prison first opened its doors in 1872, it took in the worst criminals in the West—including women and children as young as 10, simply because female- and juvenile-specific facilities didn’t yet exist. It closed in 1973 and today operates as a museum and National Historic Site. Several buildings have weathered away over time, leaving little more than the structure’s crumbling frame.

Virtually the entire prison can be explored, including cell blocks, gallows, and former barbershops and visitor centers that have since been converted into exhibit rooms. In addition to displaying images of former inmates alongside descriptions of the crimes they were convicted of, exhibits probe visitors to question the ethics of unpaid inmate labor and whether the presence of armed officials may cause more harm than good.

Advance reservations aren’t required, but the prison offers jam packed guided tours and special events such as documentary film screenings and morning yoga classes. In addition to all the usual suspects (trinkets, ornaments, and t-shirts), the penitentiary’s gift shop includes a large selection of books about the prison system itself, some of which have been authored by formerly-incarcerated people.

T-shirts and license plates

By the 1890s, the prison was electrified—but until then, all heat was generated from the region’s geothermal waters or produced by pot belly wood burning stoves. Unlike modern incarceration facilities, which rely on supplies to be shipped in, the Old Idaho Penitentiary strove for self-sufficiency, implementing work and trade programs to help it achieve its goal. Prisoners handled their own laundry, raised chickens for eggs and meat, and worked in on-site factories to produce license plates, clothing, and shoes.

Rates of pay varied from low to lower and payment wasn’t made until an inmate was released. Inmates produced far more shirts than they needed, so the prison began selling them to the general population in Boise. Disgruntled local merchants argued that the lower-priced, prison-produced t-shirts were unfair competition and the practice was a clear violation of labor laws; the shirt factory was eventually shut down.

The Outlaws

Many of the inmates housed here over the years were convicted of forgery (the most common crime), burglary, or murder. Less common crimes included adultery, bigamy, and “exposing another person to infection of a dangerous disease” (in most cases, venereal).

I’m most intrigued by the stories of inmates who utilized their artistic talents to improve their living conditions. George Hamilton, who was serving time for robbery, was an engineer by trade. He was recruited to help design the new dining hall; in exchange, the warden convinced the parole board to grant him early release. James “Blue Eagle” Erard was a talented artist who became widely known for his skills inside the penitentiary, painting at least seven large murals on chapel walls. Prison officials weren’t the only ones interested in his work; people from all around the country commissioned individual pieces from Erard.

But the general prison population was better known for its athletic achievements. The Old Idaho Penitentiary had its own baseball team (called the Outlaws) and other city and state teams came to Boise to play against them. Not only were the Outlaws good at baseball, they were also good at cheating—and they usually won. Today, the stage at the Idaho Botanical Garden, located next door to the penitentiary, sits on top of the Outlaws’ former baseball field and stadium.

Trace amounts of arsenic

Women were held for crimes ranging from adultery and bigamy to providing abortions, and “inducing a girl to enter a house of prostitution.” The Old Idaho Penitentiary housed some of the country’s first-known female serial killers, including Lydia Southard. After four of Southard’s husbands, her daughter, and her brother-in-law died within 2 years of each other—during which time Southard collected the equivalent of more than $140,000 in life insurance payments—the local sheriff became suspicious.

Investigators found trace amounts of arsenic in Southard’s old pans, exhumed the bodies, and determined that she had boiled fly paper to extract arsenic in order to poison her victims. After serving 10 years, Southard escaped with the help of a recently-released convict she had promised to marry. Eventually, she was recaptured and served another 9 years before she was granted parole. Regarded as one of Idaho’s most notorious prisoners, Southard’s 19-year sentence was the longest served by a female inmate at this site.

Some would argue that the women of the penitentiary had it far easier than the men. Considered to be “idle prisoners,” they weren’t required to wear a uniform or maintain a job (although women were responsible for “household jobs” such as laundry and cooking). They could roam the women’s ward at their leisure, and in their free time, many knitted, read, watched TV, played cards or piano, listened to the radio, or worked in the gardens.

The prison’s first garden was established by an inmate wishing to be more “industrious” and wanting to demonstrate good behavior. While most of the gardens tended by inmates “belonged” to them, some of the roses were owned by the prominent Jackson and Perkins Seed Company out of Portland, Oregon. Due to its extremely hot summers and very cold winters, Boise was the perfect laboratory to test the viability of different seeds. A handful of these prison-grown rose varieties have long been discontinued, but they can still be found growing on the penitentiary’s grounds.

If you go

The Old Idaho Penitentiary is open daily from 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. (last admission is at 4 p.m.).