“I don’t think you’re going to find anything,” I said, as Andy crawled beneath the sea green 1965 Plymouth Fury III that we’d taken to calling ‘Furiosa.’

“Well, here’s a huge exhaust leak,” Andy shot back. “Which might explain why I’ve had a headache for the last three days.”

Keen to find the car’s every fault, he rolled over to the passenger-side wheel. He grabbed and shook it. It rocked back and forth in his hands, emitting an alarmingly loud rattle akin to a slow-motion jackhammer. “And the right-hand steering idler arm is barely hanging on.”

I giggled to cover my nervousness. Should we continue in what was looking increasingly like a 53-year-old death box, or lose a day—at best—seeking out replacement parts?

Andy rolled out from under the Plymouth. We locked eyes and had a silent conversation. It was settled.

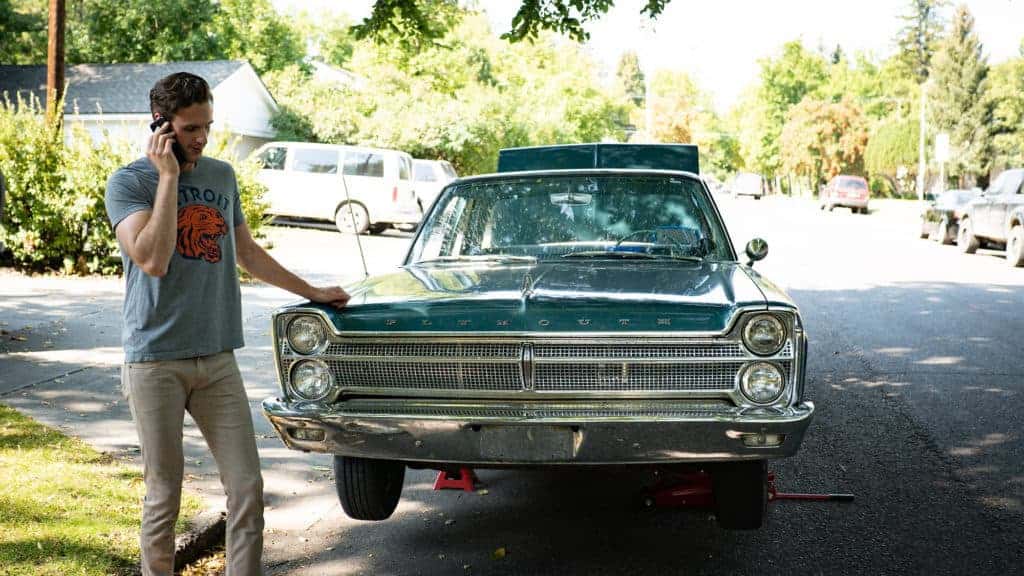

I immediately got on my phone and began calling local auto parts stores. Andy dialed auto repair shops.

Though we were still some 1,730 miles away from Detroit, our final destination, we’d be stuck in Bozeman, Montana until the Plymouth was, if not fixed, at least not trying to poison us.

Friendship is rare

I spent nearly two virtually friendless years in Detroit. And I didn’t meet Andy until two months before I moved away.

In October, 2016 I relocated from Los Angeles, California to Detroit, Michigan for a job with General Motors. I hadn’t been living in LA very long, having moved there from my hometown of Portland, Oregon just 13 months prior—also for a job.

I quickly discovered my Detroit experience would closely mimic that of my time in LA. By that I mean: I’d be mostly lonely.

In LA, since my friends were spread across the city, my social life fell victim of the city’s vast size and its congested roads. Neither my friends nor I really wanted to spend two hours in traffic—each way—on Friday night just to grab a couple beers together. So we stayed home.

In Detroit, however, population and infrastructure weren’t the culprits; I was lonely because I was single.

That’s because everyone in Michigan, by my approximation, gets married by 26. And I quickly discovered that, unless you’re married, people—couples, really—wanted little to do with a third-wheeling man in his thirties. I spent my time in Detroit alone, doing what most people do when they’re not punctuating their lives with twice-yearly Instagram-ready photos: I hung out by myself.

Of course, two months before I would move back to Portland, I met Andy.

On a Saturday in early May, I sat inside a warehouse in downtown Detroit next a few strange men. We were there to discuss the formation of a car enthusiast club.

A guy in his early 30s wearing black jeans, a black t-shirt, and a Patagonia trucker cap paced in and out of the room, smartphone pressed to his ear. We were all waiting for him to finish his call, since he was the one who wanted to start the car club in the first place. Plus the warehouse was his.

On his fifteenth reentry to the office, the guy in the black t-shirt stopped at the whiteboard at the end of the conference table and scrawled, “Andy is buying a house.”

He was Andy.

We became fast friends. Andy is one the nicest guys I’ve ever met. He’s quirky and generous. He’s also industrious and whip smart. He’s like a scrappy Elon Musk, but, you know, nice.

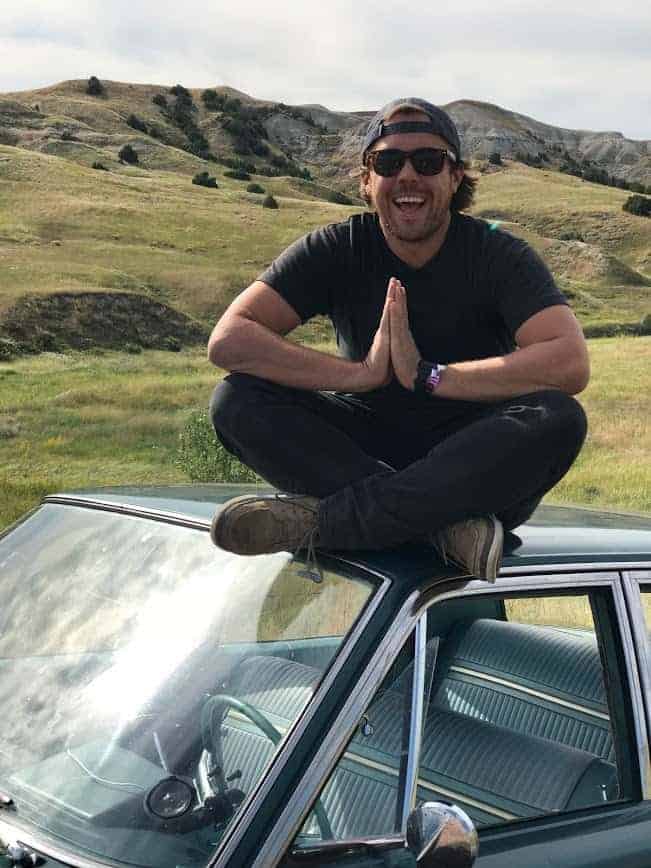

Andy lives inside a warehouse full of junker cars, motorcycles, and buses—all remnants of his businesses, past and present. Like me, Andy loves weird automotive adventures.

A few weeks after we’d met, Andy, his friend Darko and I drove down to Toledo, Ohio. Darko—yes, that’s his real name—was a Macedonian exotic-car salvager with a head of shoulder length hair that would make Hercules blush, which he accented with brightly colored, but food-stained, Hawaiian shirts. If Darko lived in LA, you’d know his devil-may-care look was meticulously manicured. Since he lived in Detroit, though, it was probably just a lucky mix of genetics and laziness.

The three of us drove down to Toledo that evening because Andy wanted to check out a Lincoln Town Car stretch limousine he’d spotted for sale on Craigslist. Did he need a limo? No. Did he want one? Well, it was a pretty good deal…

ANDY IS ONE THE NICEST GUYS I’VE EVER MET. HE’S QUIRKY AND GENEROUS. HE’S ALSO INDUSTRIOUS AND WHIP SMART. HE’S LIKE A SCRAPPY ELON MUSK, BUT, YOU KNOW, NICE.

We didn’t buy the limo; it was too rusty. That evening, before driving back up to Detroit, we dined on hot dogs and cheap beer at Tony Packo’s, Toledo’s finest steel-mill-adjacent food establishment. The dark burgundy walls of Tony Packo’s were lined with hundreds of framed hotdog buns encased in plastic, each signed by the cafe’s most famous patrons. (The signed, shriveling buns are as gross as they sound.)

Over football-sized chili dogs, Andy and I talked about the cities in which one might find non-rusty limos for sale on the cheap—the sort of places where limos were common currency, but salted roads were not. The obvious choices were America’s premier desert automotive and life-savings’ scrapyards: Vegas and Reno.

“Dude, we should totally road trip something crazy across the country,” I said through a mouthful of chili dog.

Buying a used limo was not to be, though. Each one we investigated reeked too heavily of spilled cheap champagne and vomit. That, or they simply had too many miles on the engine. But, really, most just stank.

Road trip significance

When I was a teenager, road trips were how I defined myself—or tried to.

My most memorable trip was when I was 18. My friend Zane and I bought a faded red four-door Geo sedan—from Doctors Without Borders, of all organizations—on eBay for $125. It didn’t come with a set of keys but rather a butter knife on a cactus keychain.

When we got the Geo home, we cut the roof, windshields, and doors off, and attempted to road-trip it from Portland down to Tijuana, Mexico—while wearing 1960s suits, ski goggles, and bandanas over our faces. We only made it about 30 minutes south of Portland before the police pulled us over because our car’s engine slightly caught on fire.

When the police informed us that our Geo was—in its smoldering state—illegal, Zane produced a printout of the 80-page list of Oregon laws and statutes surrounding automobiles and told the officers to prove it. Surprisingly, the police didn’t take kindly to this simple opportunity to display their legislative acumen. While we were correct that there was no law requiring a windshield, the officers had us dead to rights on not having registration or insurance.

Rather than fine or arrest us, the police escorted the Geo and us to a junkyard where Zane and I had our Geo scrapped. But not before the officers used their evidence cameras to pose for pictures with us in our motoring regalia.

With the memories of teenage camaraderie from that Geo road trip in mind that I set to work: a road trip plan for Andy and me. I wanted to craft a buddy caper film in real life—an idea inspired by nostalgia for more carefree and less lonely times.

After scouring Craigslist for a few weeks, we settled on a $3,700 1965 Plymouth Fury III with 130,000 original miles on the odometer. It was located just outside Portland—my hometown, to which I had moved back to be nearer to family and friends.

A smart man would have shipped the car back to Detroit. Andy and I were not smart. We were instead full of unextinguished angst and foolhardiness, the fuel for many great ideas.

Along the planned route, we put pins in Bozeman, Montana; Mount Rushmore; Sioux Falls, South Dakota; and Chicago, Illinois as our intended layovers. Of course we’d detour along the route when we’d catch a whiff of adventure.

On the road

Our first scheduled stop was Bozeman, Montana. We got waylaid in Spokane, Washington en route to Bozeman, though, when Furiosa’s trunk lock jammed. We were forced to spend a couple hours in an Ace Hardware parking lot jury-rigging it open. You know, so we could get to all of our stuff. For the rest of the trip, we opened the trunk with a screwdriver.

Inside the Fury, we were surrounded by untreated, not-so-safety glass with thin metal spars holding up the roof and framing the greenhouse. A mid-’60s American sedan is as much architectural as automotive. Visibility out is tremendous—like sitting on a metal porch placed in the middle of a highway.

So, too, it turns out, is the visibility in. With lots of crystal clear glass around us, and low-slung bench seats without headrests beneath us, Andy and I quickly realized everyone could see straight into the car and everything we were doing.

Passersby stared. How often do you see a filthy ‘65 Plymouth blowing down a rural highway under the midday sun doing a solid 80 mph? Driving an old car on the road is like participating in some sort of mid-century historical reenactment. It’s a reminder of what millions of Americans used to do without a second thought: cruise down little strips of asphalt in the middle of nowhere, protected from the wind and the rain by only steel and glass—and very little in the way of crumple zones, airbags, or UV ray-filtering window tint.

Like the gazes of strangers, there was nowhere to hide from the sun. We soon sported some flattering one-sided sunburns.

Without air conditioning, we were forced to keep the windows down. And with the windows down, the wind noise was deafening, drowning out most of the sound the tiny blue Bluetooth speaker we’d thrown on the dash could cough out. So instead of yelling embellished stories of past adventures at each other, we tried to pave the way for future embellishments, and logged onto Tinder.

I paid for Tinder Gold, which allowed me to set my locations to wherever I wanted. At first, I set it to the city we’d be rolling into that night. I quickly realized this didn’t give me enough time to make meaningful connections or even manage the logistics for a proper date. So, I would skip ahead a day and set my locations to the city after next. This way, I had a better chance of connecting with promising paramours—most of whom wisely went dark as soon as I revealed I was simply passing through town.

When cell signal dipped and Tinder could take a breather from crushing my daydreams, Andy and I sat shoulder to shoulder and stared out over Furiosa’s endless, green hood onto the sun-cooked highway and landscape ahead. In mid-September, most of the land between Portland and Detroit was rolling dry, grassy hills dotted by evergreens with a bright-blue sky backdrop. It is so uniform around the interstates that it’s hard to distinguish between pass-through Idaho, Wyoming, or South Dakota. Straight ahead was the same. Only the north and south horizons looked different. We needed some detours.

Since we’re in our 30s, neither Andy nor I were really game to rough it or to take blind risks like we might have in our late teens. But we didn’t want to miss an adventure either. That was why we were out here in the first place. We tried to induce a calculated mania.

We turned off on to back roads, far from civilization, or so we could pretend. I started to pray for a breakdown with each sputter or stumble of the engine—that’s when real adventure would find us, I hoped.

Finally, around a curve in western Montana, we spied a rock quarry dotted with vintage cars. Keen for a photo op, a leg stretch, and a bit of challenging the conceit of property lines, we pulled over and giddily ran up the slate hill.

Walking into the quarry, surrounded by sheets of red, brown, and grey stone, was like stepping out onto some alien surface. Given the number of abandoned and disintegrating vehicles, the quarry looked like it’d been haphazardly arranged and suddenly abandoned by most inhabitants, like a failed extraterrestrial colony.

Yards away, a man operating a gigantic Caterpillar moved stone after giant stone from the top of the hill to the bottom. Spotting Andy and me as we participated in our gentleman’s trespassing, he waved at us, but kept about his work. Clear across the other side of the quarry, a handful of other men silently packed slabs of slate into piles on pallets in the hot midday sun.

We poked around and snapped pictures of the junked classics that dotted the quarry. Why the place had a near one-to-one ratio of piles of shale to rusting, vintage car, Andy and I weren’t sure. What’s even more unclear is why some of the vehicles were stacked. We were too timid to ask the workers, who went about their jobs.

While Andy took pictures of the quarry, I staged Furiosa in front of a couple of the mostly-scrapped classics for photos of my own. Andy watched from above, as I tried to frame the wrecks through Furiosa’s open driver’s window.

When, in wrangling for the perfect picture, I backed Furiosa into a boulder, Andy got annoyed enough to demand we get back on the road. We piled into the Plymouth and peeled out of the dusty quarry.

With the sun setting, we rolled up the windows and hunkered down for the several hour drive to our next overnight in Bozeman, feeling better, but annoyingly, still a bit queasy.

Bozeman

Our hosts in Bozeman were Wes Siler—a writer for Outside magazine and Andy’s old pal—and Wes’s fiancee, Virginia. The couple had recently moved to Bozeman from Hollywood with their two dogs, animals who live better lives than most human children.

Wes stands about five-foot-ten, with a crooked smile and cropped, greying hair. He’s slender but fit and always dressed in a black tight cotton t-shirt and slim-cut hiking pants with a pair of stylish hiking boots on his feet. He looks like a fashion-forward militia man—maybe a West Point grad, if West Point were sponsored by Patagonia.

Wes is the picture of inviting and hospitable. It struck me that Wes wants to be—above all else—a man’s man. And to Wes, a man’s man is a strong, powerful, and welcoming host.

Virginia hails from Dallas and is very much a Texan. Five-foot-six, with shoulder-length blonde, and equally as fit as Wes—a good pair. They both loved to tell stories about their adventures, missing no opportunity to embellish them a bit with action.

Wes and Virginia welcomed us into their stunning home, located blocks from downtown Bozeman. It had been built in the 1940s but remodeled just a few years ago. Everything was covered in hardwood. The design was understated but sturdy. You could tell no expense was spared during the remodel. Even the fixtures were elegant, but still somehow rustic. The house—like much of Bozeman itself—made me feel deeply inadequate.

In anticipation of our arrival, Wes prepared a massive prime rib. He cut the hunk of cow into three loincloth-sized slices—each easily three inches thick.

We settled down to the raw-edge dinner table in front of our Flintstonean repast. I watched as Wes flipped open his pocket knife and cut into his steak. Only a fork lay next to my plate—no knife at all. Andy didn’t miss a beat and followed suit; he unfolded his own pocket knife and dug in.

Bluff called.

WE SETTLED DOWN TO THE RAW-EDGE DINNER TABLE IN FRONT OF OUR FLINTSTONEAN REPAST. I WATCHED AS WES FLIPPED OPEN HIS POCKET KNIFE AND CUT INTO HIS STEAK.

“Can I have a steak knife?” I asked. Virginia graciously retrieved one for me from the kitchen. “I have a pocket knife, too, it’s just in my…” I trailed off, feeling embarrassed that I hadn’t prepared with my own personal meat dismantler.

Is he going to wipe it off on his jeans when he’s done? I bet he does, because that would be badass. And this dude never misses a chance to be badass. (He didn’t. He should have.)

As I broke down the beef with my civilian tableware, Wes regaled us with stories of hiking, fighting, and his newest acquisition: a bear pistol. You don’t go anywhere outside the city without bear mace or a gun, we learned—or, ideally, both. The bear population had exploded in recent years, which is the last thing you want the bear population to do … unless you’re a bear. Wes never appeared to want to have to deal with a bear encounter, but as table talk, it put Bozeman in relief. There was a lot of wild country still around these beautiful homes.

During dinner, Andy still felt ill. He jokingly blamed carbon monoxide poisoning. I felt mostly fine, though, and I had been in the car with him all day. If it were carbon monoxide poisoning, I assumed I’d feel its effects more profoundly.

Wes and Virginia were more concerned for Andy’s well-being than I was. She confessed she was a light sleeper and insisted that, if Andy needed to go to the hospital in the middle of the night, he shout for her. Taking potentially life-threatening issues seriously came a little easier to these outdoorspeople.

It turns out Andy was feeling the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Under the car the next morning, caution led us to discover an exhaust leak underneath the Fury’s cabin, slowly dribbling poisonous exhaust into our otherwise clean, temporarily western lungs. Suddenly, the last few days took on a new color. We’d done something slightly risky, in a calculated way, and nearly done some real damage to ourselves. We opted to stay in Bozeman an extra day to button everything up.

Sideline adventures

If I’m being honest, my hopes for this trip—more than fixing engine troubles or discovering amazing detours—I wanted to have an experience that would stand as some sort of milestone. I wanted a trip that would put to rest three lonely years of playing the drums by myself in my basement on weekends and catapult my vigor for life back to its twenty-something peak.

Mid-way through the trek, I was having a blast with Andy. We laughed a lot. Yet nothing really stood out. Nothing felt worthy of retelling for the next half century, like Zane’s and my adventure with our Geo had been.

I kept judging myself: perhaps there was no outside stimula, no sideline adventure, that would ever outshine or even match the meaningfulness of the road trips of my teens and twenties.

Somewhere in Wyoming around 10:30 p.m., still a few hours shy of our Airbnb, we pulled off the highway. We’d been up for 16 hours, but Andy wanted to get a shot of the Milky Way.

For the first time in a long while, I wasn’t hot. Furiosa was like a drafty old house: hot during the day and bitterly cold once the sun went down. As the Plymouth idled on a highway service road, I caught a chill and put on my coat.

From the passenger seat, hands in front of the heater vents, I did nothing but listen to the steady drum beat of the idling V8 engine. Through the windshield, I watched the rare car pass by on the highway—headlights and taillights phosphoring through the night in front of me. Outside, Andy aimed his camera skyward in the darkness. I felt like I needed to set the mood. I cued up Tenacious D’s first album on Spotify.

Andy got his shot, hopped in, and threw his camera in the back seat. He pulled Furiosa’s shift lever down into drive and we took off into the dark, back onto the near-deserted Wyoming highway. I pressed play and we shouted along with the music.

In that moment, blurry-eyed and weary from hours of travel, I was overwhelmed with emotion. Perhaps it was latent carbon monoxide leaking into the cabin, or perhaps it was real. The D’s song “Friendship” began to stream. We shouted along with Jack Black and Kyle Gass—two idiot friends.

In the deep, rural Wyoming darkness, long after our smartphones lost signal, we found our way to a tiny house we’d rented on Airbnb—our resting place for the night. Whooped, we stumbled inside, climbed into the bunk beds, and passed out.

The next morning, we were woken by the bellowing of steers. My eyes shot open and came into focus on the cactus-print sheets. I looked around the tiny house. It was decorated with cowboy accents throughout, splashes of turquoise and red all around.

Andy and I dressed and stumbled outside to find the source of the bellowing. We discovered our tiny house was literally in the middle of a working ranch called “Krell’s Korral.” I had chosen the tiny house on Airbnb simply for its location, cutesy interior decor, and hilarious bunk beds. I had thought it was “ranch flavored.” I hadn’t expected it to actually be on a ranch.

We choked down some Folgers that I poured from the scorched single-serve coffee pot and packed up the Plymouth. I organized the bags in the screwdriver-accessed trunk. From the corner of my eye, I saw the screen door of the larger ranch home nearby fling open. A short-haired, ample woman tilted towards us in a dark blue mumu. She introduced herself as Bev.

Five generations, Bev told us, had lived on the ranch. Her grandparents homesteaded the land in the early 20th century and now she and her husband lived in the main house. And her son and his wife and kids lived in the single-wide trailer behind the barn, which was overrun with blind, inbred barn cats.

Bev had the tiny house built not for renting, but when she became obsessed with them after watching endless hours of tiny house programs on HGTV. But she didn’t want to live in a tiny house, so she put it on Airbnb.

Bev quickly excused herself, admitting she had breakfast plans with her daughter that she was late to. She climbed into her pinstriped dark blue Chevy SUV and left Andy and me alone on the ranch. We finished packing the Plymouth and beelined it for Mount Rushmore.

Please, don’t disturb the president

Everyone warned me that Mount Rushmore would be less impressive in person that I would expect. I found it to be the opposite. Sobering, for some reason, not amusing. I sat in the hot South Dakota sun and listened intently as the park ranger colorfully recited the history of the place.

The ranger mentioned that, a year previous, a visitor fell into hysterics when the ranger informed her that Barack Obama was not going to be carved into the granite. Upon hearing this, a group of geriatrics next to me murmured in dismay.

“Should be Trump!” one shouted.

Unlike Mount Rushmore, the National Presidential Wax Museum is a funny place.

The museum’s hallways lead you past sparse scenes designed to depict the various presidents’ finest achievements. Obama was shown promoting healthcare. Trump was standing in front of his plane. George W Bush was at Ground Zero with a megaphone in hand. And a fat, 49-year-old Grover Cleveland was shown marrying 21-year-old Frances Folsom.

I waited until the coast was clear. I backed up to the white painted metal fence, with the wax figure of the 45th president of the United States behind me, and launched into my best Trump impression. Seconds into my nonsensical monologue—somewhere around, “Believe me, bigly”—the shrill, blaring motion alarm sounded.

When the alarm sounded for the third time, the woman working the front desk at The National Presidential Wax Museum in Keystone, South Dakota rushed in and disabled it with what appeared to be a long TV remote. She pleaded, “Please, don’t disturb the president. That’s a $70,000 figure.”

Not long after we were alarmed away from the Trump display, Andy discovered a glass case in a dim corner a sculpture we dubbed “Zombie Lincoln,” a wax bust of what I imagine Lincoln would have looked like if he were stranded on a desert island, yet still made of wax.

Just below that was another long-haired, scraggly-bearded Lincoln. He had one eye half open, his mouth agape, and a pert left nipple. Weeks later, I still can’t figure out why they made such a thing, nor why they don’t sell replicas as souvenirs.

As we exited the museum, we spotted socks for sale emblazoned with various presidential likenesses, including Kennedy, Trump, and, for some reason, Vladimir Putin. I wish I’d bought the Putin socks.

2,700 miles later

Since we lost a day in Bozeman repairing the Plymouth, and I had a plane to catch in Detroit three days hence, Andy and I had to rocket through most of eastern South Dakota, all of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois. From an overnight in Chicago, we drove straight to Detroit, where Andy dropped me at the airport a few hours before my flight.

We didn’t really say goodbye. I just grabbed the screwdriver, opened the trunk, grabbed my bag, and walked inside the terminal. And that was it. Our big, amazing road trip was over.

In six days, Andy and I put nearly 2,700 miles on the Fury. Before we left, I was sure disaster would befall us. Andy, however, expected nothing to go wrong. For better or worse, it’d been somewhere in the middle.

We didn’t find ourselves wholly reborn. Our near-death experience was pretty mild—carbon monoxide poisoning isn’t a joke, but we had the tools, knowledge and resources to address it. We lost a day waiting around for half-century-old steering components. Aside from that, the trip went off without a hitch.

I sat ruminating at my gate, awaiting my flight to Portland.

After Andy and I had left the wax museum, we had driven to the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site. We pulled up shortly after it closed to find the gate locked and parking lot deserted. We parked the Plymouth in front of the large, white triangular gate and climbed over it.

Andy had waltzed up to the door of the big, red brick building and pressed his face against the glass. Like the parking lot, the museum was dark and deserted.

Bummed he had missed the nuclear silo tour, Andy pulled out his phone and looked at maps of the site. He realized two other missile silos were placed across the empty highway in a grassy field. He loped over to them in the dark.

When I caught up, he was staring at his phone at the edge of two large ponds, checking his map.

“They must have filled them with water and made the other into a museum,” Andy said.

We stood there a minute, just looking at the ponds, former nuclear missile silos; two 30-something guys standing on the edge of something once-powerful decades after its prime. We were too late. And we knew it.

I leaned into black vinyl airport chair. The sounds of roller bags and flight announcements echoed in the clinically clean terminal.

Why wasn’t this trip as good as I wanted? Why wasn’t more special?

I was never going to make up for the last three years. I was never going to have an adventure as good as the one Zane and I had with the Geo. Maybe I was too old, too safe for that kind of stuff now. Things felt like they went too quickly now for me to really enjoy.

Funny thing about adulthood, that everyone hears again and again, but you can’t really understand until it happens to you: time goes much faster for me now than it did 15 years ago. Weeks fly by, when they once used to drag. The easy rhythm of living sucks some of the sweetness out of life.

I used to think that the Geo that Zane and I bought at 18 was the gimmick; the car was what made the story special and worth retelling. Really, the Geo was nothing. It’s the connection I’ve shared with Zane for the last two decades that’s stuck around.

Driving across the country in a half-century-old V8 American sedan was a dream come true for me. We did it. It was done. Back to routine. The tales will get taller in the retelling—”We started hallucinating herds of buffalo after nearly dying from carbon monoxide poisoning!” “We were nearly arrested for breaking into a nuclear missile silo!” “We actually met a woman on Tinder!”—but they won’t be told the first time by the 18-year-old I once was, dumber, and braver.

But they won’t be told alone this time, either, not like the last three years. They’ll be told with old friends again, and new.