It’s early September as I pull off the highway in Southeast Pennsylvania to refuel and recharge. I’ve been driving for less than two hours, but inexplicably heavy Friday afternoon traffic has numbed my mind and atrophied my extremities. I’m in desperate need of a rest stop and I pick one seemingly at random—but as soon as I pull off onto the exit ramp, I feel a wave of déjà vu. The name of the town, Shartlesville, triggers my mind to shuffle through its dusty card catalog of roadside attractions and then I spot a sign confirming my suspicion that I have, indeed, been down this road before: “Roadside America, the World’s Greatest Indoor Miniature Village.”

Roadside America is so much more than just a name to describe a miniature village that resides within a nearly 8,000-square-foot building visible to anyone traveling highway 78. For those familiar with classic roadside attractions and those who relentlessly seek out the last vestiges of Americana, “Roadside America” is a state of mind.

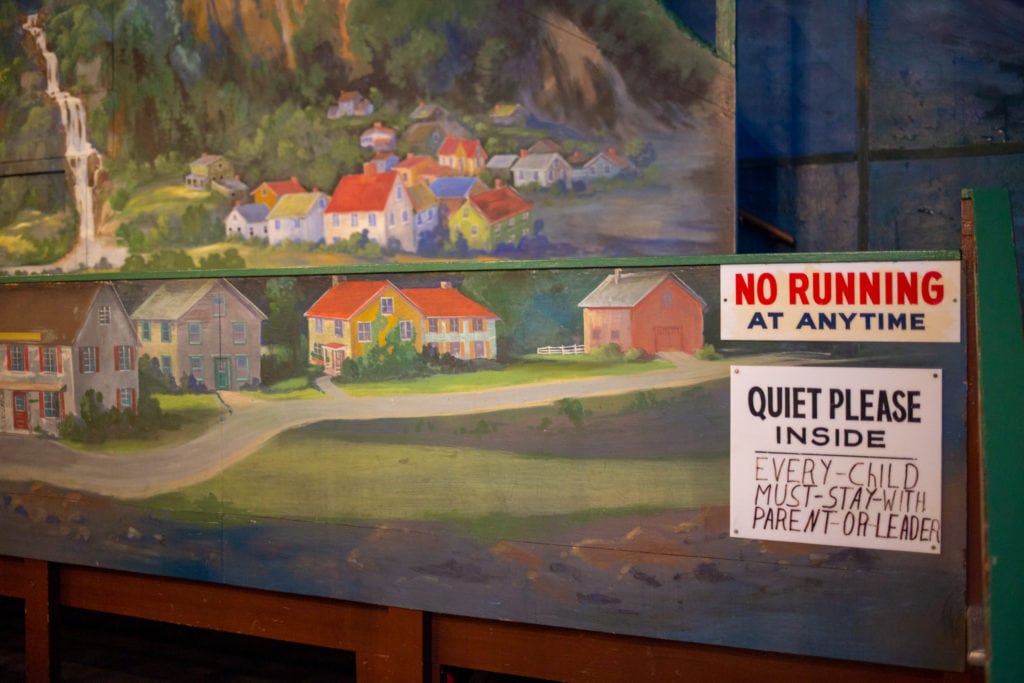

Roadside America is located just off interstate 78 in Shartlesville, Pennsylvania. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A Hex sign outside of Roadside America. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A sign in the gift shop lets visitors know what they’re in for. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A pond features real live goldfish. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Pastoral hand-painted scenes cover every surface of Roadside America. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

But only one attraction bears the name and in the 66 years since it opened its doors, Roadside America has welcomed several generations of weary travelers like myself, people in search of a place to stimulate the mind and stretch the legs. The classic attraction has remained virtually unchanged over the years and under the stewardship of the same family since its inception. But nothing stays the same forever and Roadside America is currently for sale—with the stipulation that any interested party agrees to keep the attraction exactly as it is, and has been since 1953.

600 light bulbs and 10,000 trees

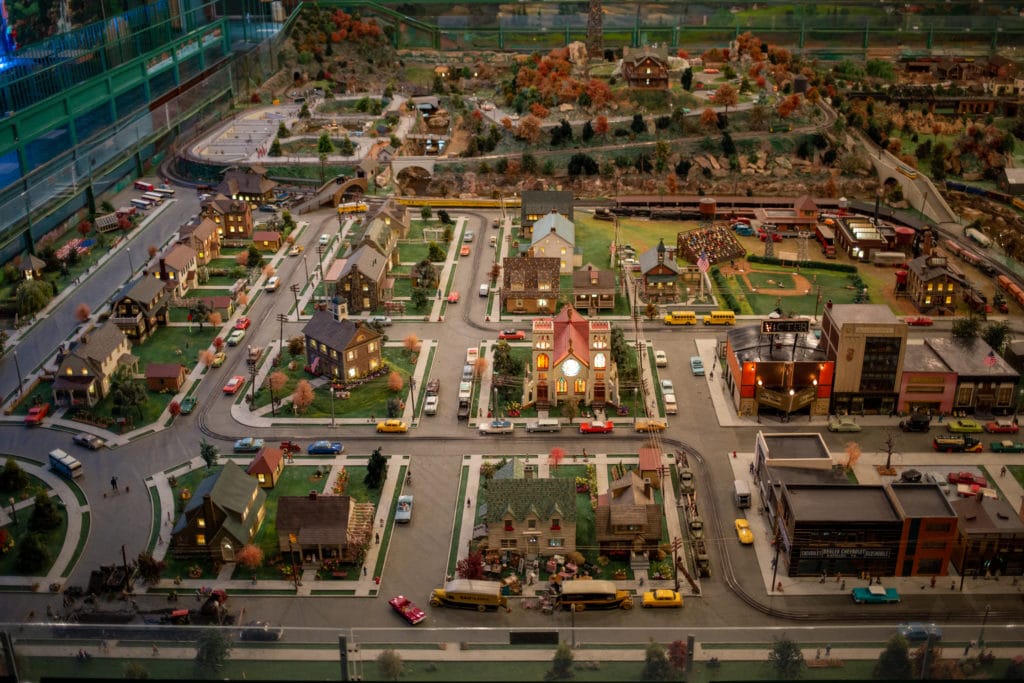

My first visit to Roadside America was on purpose, but my second is serendipitous. A sign in the gift shop warns visitors, “Who enters here will be taken by surprises—be prepared to see more than you expect! You will be amazed at Roadside America’s beauty and mechanical skill—over 50 years in the making by our family. You and your children can run the trains, trolley, etc. etc.” Those two “etceteras” are a drastic understatement. Roadside America is an epic tour of 200 years of American history told through thousands of miniature figures, buildings, and vehicles at a scale ranging roughly from 1:32 to 1:54.

Even on my second visit, I’m still amazed. This is not your typical holiday train display; the scale and scope of Roadside America is staggering. The open space and tiny villagers—unobscured by beams or pillars—make me feel as if I have fallen down the rabbit hole and nibbled a cake labeled “Eat me.” There’s nothing like a room full of miniatures to mess with your perspective and make a person feel larger-than-life.

Depending on your point of view (or age) Roadside America is either an outdated time capsule or a celebration of what makes America great. The display includes an open-air zoo, a playground, town squares, cemeteries, an ice skating rink, service stations, department stores, movie theaters, log cabins, modest homes, a circus, caverns, lakes, oil wells, farms, country clubs, four cathedrals, etc., etc. If it existed in rural America before the 1960s, chances are it’s represented here—with 300 buildings, 600 light bulbs, 4,000 figurines, and 10,000 trees.

“There’s nothing like a room full of miniatures to mess with your perspective and make a person feel larger-than-life.”

“People want to relive their memories of what life was like before cell phones and computers,” says Jeff Marks, Roadside America’s resident restoration artist. “That’s what’s amazing about this place—yes it’s moldy and musty but when you enter it’s the 1950s all over again. It’s a look back into our history.”

These aren’t just static displays. Although the mechanics may seem antiquated to modern visitors, Roadside America is still very much full of life. Dozens of trains and trolleys zoom constantly around the room (on their own and at the push of a button). Visitors are encouraged to participate in bringing some of the elements to life: Press one of more than thirty buttons and oil wells bob up and down, donkey’s heads nod, and a cavern illuminates. Don’t miss the five-minute “night pageant,” which occurs every 30 minutes—I won’t spoil the surprise but I will say that it’s spectacularly bizarre.

One man’s America

Unlike the real life America, this miniature, idealized version started with one man: Laurence Gieringer. Around the turn of the century, when Gieringer was a small child, he and his brother Paul got lost attempting to climb Reading’s Neversink Mountain. Although they were eventually rescued, the view from above inspired Gieringer to begin building miniature villages (Paul became a Catholic priest and a painter—some of his work is on display in the gift shop).

Like Rome, Roadside America wasn’t built in a day. In 1935, Gieringer’s living room display of miniatures won first prize in a Christmas contest. The collection would grow and move several more times—to a Carousel house in Carsonia Park, then to a former dance hall in Hamburg, Pennsylvania—before Gieringer built a warehouse in 1953 specifically to display his life’s work. Although Gieringer died only 10 years later, the attraction has been lovingly maintained and today, Gieringer’s granddaughter, Dolores Heinshon, is in charge.

Like so many others, Heinshon grew up at Roadside America. “I can remember riding my little red tricycle with a bell on it here,” she told the Reading Eagle. “I know every little item and the stories behind them.”

Heinshon may be ready to retire, but she has no intention of facilitating the demise of her family’s beloved roadside attraction. Jon Jordan, who introduces himself as Roadside America’s “village supervisor,” confirms that the attraction is indeed for sale, but with one crucial caveat: “The family is committed to passing it on to someone who will have the passion to keep it open and keep it going,” he says.

Jordan—who looks to be in his early 20s—loves Roadside America so much that he once brought a date here. At some point during the date, he noticed a “Help wanted” sign and didn’t hesitate to apply. “When I was a kid I just knew it as the ‘push button train place,’” Jordan says. “But now I appreciate the artistry.”

There are a few full-time people on staff—Jordan, Marks, and Richard Peiffer, the track, train, and trolley foreman—and they all share the same mission: “To preserve [Gieringer’s vision] and keep it the way it is,” Jordan says. “It’s a fun job.”

“We’d all come here as kids,” Marks adds. “We have the passion for it. We want it to run for another 60, 80, 100 years.”

Make trains cool again

Although Peiffer admits he has a “wish list a mile long,” he estimates about 95 percent of what visitors still see is Gieringer’s handiwork. What Gieringer didn’t make by hand, he purchased from various sources, including Britain and France. Most of the figures (mostly cast in lead or plastic) are bonafide antiques and many of the materials Gieringer sourced simply don’t exist anymore.

“None of this was from a kit,” says Marks, who was making miniatures as a hobby until he got hired as Roadside America’s restoration artist three years ago. “You can’t buy this stuff anymore,” he adds. “There is no longer a demand for it and every year it becomes harder and harder to acquire miniatures.”

Featuring 44 hand-painted windows, the Fairfield cathedral took more than 400 hours to complete. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The handcrafted details are extraordinary. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A three-ring circus display no longer rotates. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Hand-painted figurines. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Ice skaters overlooking the village. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

He points out the circus display, which no longer rotates. “I want to get that working again,” he says. “But now real circuses are even becoming defunct.”

Frustratingly, it’s nearly impossible to see and appreciate all of Gieringer’s work because Roadside America is both too large and too small at the same time. Visitors can simulate Gieringer’s mountaintop epiphany by climbing one of two staircases in the room for an aerial view, but much of the display’s details are out of reach.

Perhaps because of this—and the dim lighting—Marks says that the display doesn’t need to be cleaned as frequently as you might think, but it’s a monumental task, nonetheless (usually done in the slower winter months). “The buildings are so solid, you could sit on them,” he says. “I was terrified of falling or stepping on something, but you just have to have good balance and plan your route in advance.”

Marks also grew up with Roadside America and his affection for the attraction is palpable. “Who wouldn’t like working here?” he asks. “Doing something you love is exhilarating—I’m putting my talents to use for something. Children’s smiles make me smile and I think, ‘Yeah, it’s worth it.’ Every day I’m accomplishing something.”

Although Marks also has a wish list of his own—including better lighting and an upgraded sound system—he thinks the attraction’s 26 acres are rife with potential (the asking price is $2.3 million). He suggests adding a miniature golf course or an ice cream shop to entice visitors to pull off the highway all year round. “We need that resurgence,” he says. “It could be a destination again.”

A cemetery with miniature headstones. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Laurence Gieringer died in 1963. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The display includes four elaborate churches. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Nearly everything was handmade by Gieringer himself. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A train in Richard Peiffer’s workshop. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Richard Peiffer’s workshop. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

It’s almost redundant when Peiffer, who is wearing a baseball cap stitched with the words “Make Trains Cool Again,” tells me, “I’m very passionate about what I do.” He has plans to repair a miniature airplane that crashed at some point before he came to work for the attraction three years ago. He would also love to upgrade the theater’s Depression-era lighting and other behind-the-scenes mechanics, while ensuring that he doesn’t “ruin the integrity of the display.”

Peiffer vividly remembers visiting Roadside America in 1968, when he was just five years old, and now that he’s found his dream job he has no plans to leave. “I’ll go wherever [the display] goes,” he says. “But I think it’s going to stay put.”

Whatever becomes of the attraction, Marks hopes that he—along with Jordan and Peiffer—will be a part of it. “We don’t have the funding, but we have the heart for it,” he says.

Roadside anachronism

When road travel exploded in the ‘40s and ‘50s, roadside attractions were popping up like weeds along popular routes. Roadside America was built along what was then Route 22 (current day Interstate 78) in the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch Country. The players and pace of life on the road may have changed, but plenty of travelers still see the value in attractions like Roadside America.

Marks says that Gieringer’s vision is especially popular with international tourists. Buses carrying people from European and Asian countries frequently stop to see the self-proclaimed “World’s Greatest Indoor Miniature Village.”

“This is the quintessential road trip destination,” Marks says. “They’re discovering America here.”

Today, visitors can shop for Hex signs—featuring brightly colored, geometric Dutch folk art—at the Penna Dutch Gift Haus next door. It also features relics from Roadside America’s stint as a print shop (Gieringer was a “jack of all trades,” Jordan explains). If you’re lucky, Heinshon herself might be behind the small lunch counter to serve you a homemade slice of shoo-fly pie (or you can take home an entire pie for $6).

An Amish couple welcomes visitors to Roadside America. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A billboard urges travelers to turn back. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

A fiberglass Amish couple sits silently on a platform in the parking lot between the two attractions, and a hand-painted billboard facing southbound traffic succinctly alerts travelers to what they may have missed: “Roadside America. Turn back. Next exit.” Another hand-painted sign near the register declares: “If you are skeptical, and think this might be overrated or overpriced, etc. ask any visitor or patron coming out.”

Heinshon may have put a price on Roadside America, but to so many of us it’s priceless (and more than worth the $8 admission price). Marks agrees: “[Roadside America] has held on for all these years—that’s what’s so amazing about this place. In this day and age, having something like this is an anachronism. Places like this just don’t exist anymore.”

If you go

Roadside America has closed indefinitely.