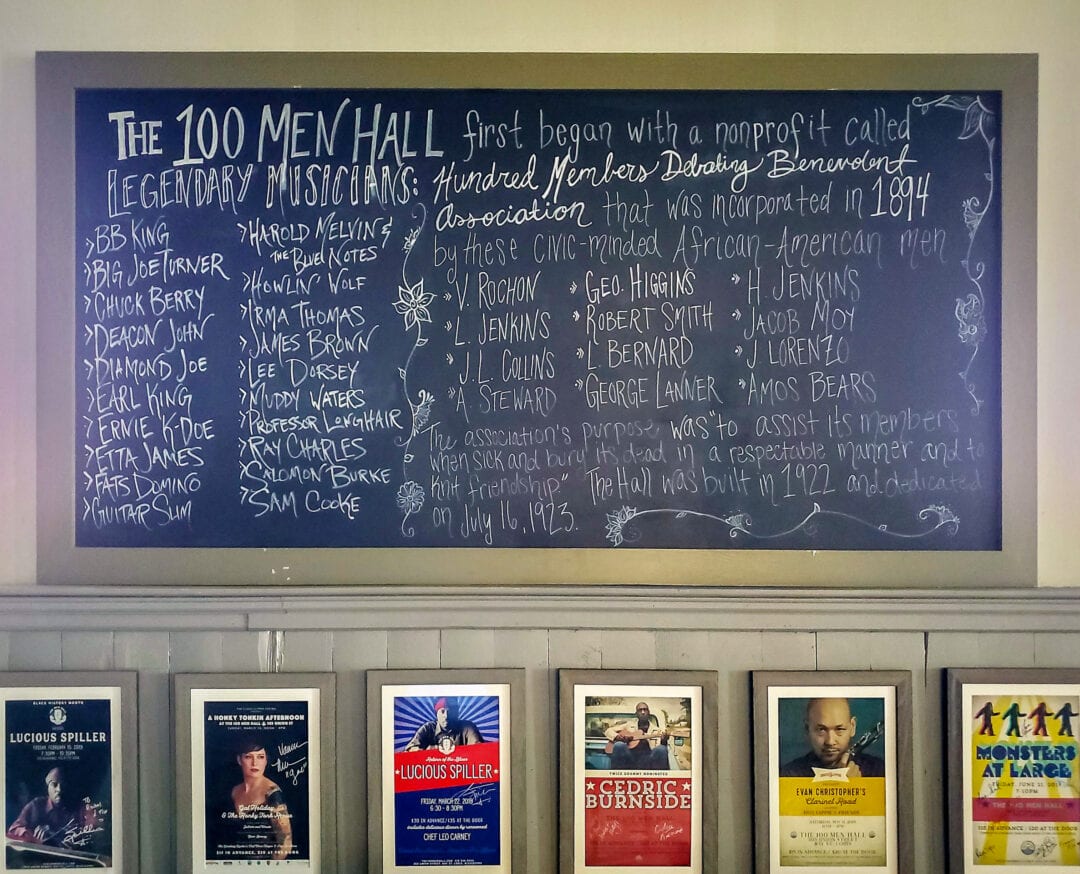

In 1894, 12 African American men in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, formed the Hundred Members Debating Benevolent Association (DBA) and penned its bylaws: “The purpose of this Association is to assist its members when sick and bury its dead in a respectable manner and to knit friendship.” In 1922, members laid the cornerstone for The 100 Men Hall and built the clapboard building that still stands today. The club quickly became a place for Bay St. Louis’ Black community to gather for life’s celebrations, to knit friendships, and find joy.

When Rachel Dangermond toured the 100 Men Hall in 2018, she says, “I knew right in that moment that this is what I was doing, buying the Hall, moving in here with my son.” Then, she did just that, dubbing her son Constantin the “101st man.” Originally, she planned to hold writers’ workshops here, but the building’s Black history and significance prompted Dangermond to return to its roots.

Over the years, the hall has hosted everything from baby showers and bingo games to graduation parties and weddings. Even the building itself has proven resilient—hurricanes Camille, Katrina, and Zeta all battered the structure, but it survived.

“The 100 Men Hall tells a more nuanced story than what you will hear about Mississippi in this country,” Dangermond says. “It is a testament to the resilience and self-reliance the African American community had (in order) to create a place of civic activism and community joy in the midst of this country’s dark times of Jim Crow and segregation.”

Community comes first

The hall’s use as an entertainment venue was a way for the 100 Men DBA to generate the money they needed to help community members. When she was just 14 and her family’s home burned down, Queen Isabella Williams experienced the generosity of the association firsthand: “Until my mother could find us a place, we came and lived here,” Williams says.

To strengthen ties between the community and the hall—and to learn first-hand about the 100 Men DBA—Dangermond launched the 100 Men Hall People Project, inviting anyone with a connection to the hall, like Williams, to share their experiences. Portraits of the participants by photographer Gus Bennett hang in the hall.

Russell L. Nichols, who says he’s “the last man standing of the 100 men,” joined when he was 14 years old. “My grandmother, Eretta Benoit, promoted dances here,” Nichols says. “She brought people here that are listed on the wall, [including] Etta James, Ernie K. Doe, and Joe Turner.”

The 100 Men Hall People Project helps paint a picture of the hall’s history, the generosity of the 100 Men DBA, and how it served the Black community. Those sharing their experiences with the project mention everything from paying nickel dues to performing as go-go dancers wearing sequined costumes and knee-high baby blue boots.

Chitlin’ Circuit

A common thread tells of the hall’s place along the Chitlin’ Circuit. The circuit, a series of Black-owned juke joints, dance halls, music venues, and nightclubs, operated during segregation from the 1930s to the ‘60s. “A lot of Black people had nowhere to go on the coast—this was it,” Williams says.

Jazz and blues singers who played on busy weekends in New Orleans continued east on the Chitlin’ Circuit during the week. Bay St. Louis, located just an hour east of New Orleans, was the first stop, and 100 Men DBA members invited Black musicians to play Monday night dances at the hall.

“In the heyday of the hall, when it was a Black energy center, there were no TVs, movies, phones, or screens, so a lot of entertainment was homegrown,” Dangermond says.

The building has played host to an unbelievable amount of talent, with many greats gracing the hall’s stage before they became famous. A blackboard lists previous acts, including B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Etta James, Fats Domino, and Ray Charles. Concert posters advertise more recent events. The hall, a stop on the Mississippi Blues Ttrail, is now home to a mural devoted to Etta James.

Inside, a Gretsch drum set sits center stage with a Hammond B3 organ nearby. A large Frida Kahlo decoration overlooks the hardwood dance floor, a remnant from the annual Bay St. Louis Frida Fest a few years back. The Labor Day Booker Fest honors legendary pianist James C. Booker, who spent part of his childhood and learned to play the piano in Bay St. Louis. Concerts, Southern eats, and other cultural events round out the hall’s calendar. In June 2022, Wwhen the hall’s year-long 100th-anniversary festivities kick off in June 2022, musicians from the venue’s earlier years will headline alongside up-and-coming acts.

100 Women

Beyond returning the hall to a gathering place and music venue for the entire Bay St. Louis community, Dangermond says she “wanted to resurrect the nonprofit that had been the organization behind the building. After years of community work and activism, I knew in my heart that it is the women who do the kitchen table organizing that makes a difference in our communities, so the 100 Women DBA was born.”

Dues-paying 100 Women DBA members help support the hall and, like their predecessors, address immediate needs of locals. 100 Women DBA also promotes tolerance and fosters community. And the hall couldn’t be a better home base for their mission.

“There’s an energy that never left from back when it was the place to be for Black folks in the area,” Dangermond says.

If you go

The 100 Men Hall hosts events and can be rented out for private functions including conferences and weddings.