If you look at a map of Vermont, you’ll find Bennington in the southwest corner, bordered by the Green Mountain National Forest on three sides, and New York State to the west. It’s as if someone took a bite out of the forest—but instead of crumbs they left impossibly charming historic homes, white clapboard churches, and colonial cemeteries. At the center of the Old Bennington Historic District, West Main Street (aka Route 9) curves nearly 180 degrees, cradling the Old First Church and the oldest burying ground in the state of Vermont, Bennington Centre Cemetery.

In a state full of idyllic and charming towns, Bennington is an over-achiever. From a distance, it looks as if the artwork on an artisanal cheese label came to life. Chartered in 1749, it’s the most populous town in Southern Vermont and the third-largest town in the state. The famous Revolutionary War Battle of Bennington took place here on August 16, 1777 (the Americans won). Casualties from the battle—including American, British, and Hessian soldiers—are buried in Bennington Centre Cemetery.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison once stayed across the street at the Walloomsac Inn, which now sits in such a glorious state of decay that visitors lured by spooky sites might miss the historic graveyard all together. The cemetery has its own share of notable residents including Revolutionary War soldiers, five Vermont governors, Titanic victim Charles Cresson Jones, and poet Robert Frost—but the real stars here are the intricate headstones, created by some of New England’s most famous and prolific stone carvers.

Symbolism set in stone

I booked a room at the Four Chimneys Inn for a night in early July, not knowing that it was cemetery-adjacent (always a plus). But a short after-dinner walk down West Main Street led me to the Old First Church at twilight—the first Protestant church in Vermont, established in 1762. The church was closed, but I found the churchyard neither locked nor gated—yet another sign that I was a world away from the big city.

Despite their proximity, the burial ground and church are no longer affiliated with each other. “People associate the cemetery with the First Congregational Church (Old First Church), but since 1907 the cemetery has been operated by the private Bennington Centre Cemetery Association,” says Lodie Colvin, secretary of the cemetery.

The first stones I encounter upon entering the graveyard are its showstoppers. New England cemeteries are full of excellent examples of death imagery—from winged skulls, cherubs, and hourglasses to crossbones and draped urns. But if cemeteries are outdoor art galleries for anyone interested in typography, symbolism, and the art of stone carving, the Bennington Centre Cemetery—featuring the work of noted stone carvers including Ebenezer Soule, Josiah Manning, and Zerubbabel Collins—is the macabre Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“The older gravestones in this cemetery are unique examples of American folk art,” Colvin says.

-

Ebenezer Soule was an itinerant carver, leaving beautiful works of art wherever he went. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Some of the earliest stones in the cemetery feature the work of Soule, who was continuing a four-generation tradition of carvers that included four sons, two grandsons, one adopted grandson, and one great-grandson. Soule was an itinerant carver, living in Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire, leaving beautiful works of art wherever he went.

Colvin says Soule probably passed through Bennington in the 1770s. His relatively simple stones are topped with heads that stare blankly forward, intricately feathered wings spread beneath them. Wigs made of curlicues are perched on their round heads, curves and swoops standing in sharp contrast with the hard stone and simple typography.

-

Josiah Manning’s winged figures look surprised or angry. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Manning’s winged figures look surprised or even angry; his simplistic, chunky shapes are reminiscent of wooden African masks or Mesoamerican sculptures. The Latin phrase “Memento Mori” (“remember you will die”) adorns one of his stones, a sentiment that Manning must have felt deeply as he was carving his own tombstone (he’s buried in Connecticut).

Manning’s two sons, Rockwell and Frederick, followed in their father’s footsteps. According to the Connecticut Gravestone Network, “The Mannings established a style of gravestone carving that became dominant in eastern Connecticut for nearly fifty years. Manning stones are present in almost every eighteenth-century cemetery in eastern Connecticut.”

-

Forty stones in the cemetery were carved by Zerubbabel Collins. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The most prolific (and fantastically-named) carver featured in Bennington Centre Cemetery is Zerubbabel Collins. Colvin says that 40 of the cemetery’s stones are believed to be the work of Collins, with five more attributed to his apprentice and successor, Benjamin Dyer. Collins, also the son of a stone carver, moved to Vermont in 1778 and began working with white marble. His stones are elaborate and highly decorative, full of flourishes and floral motifs, topped by winged heads with blank stares and solemn faces.

“These gravestone carvers developed a distinctive regional carving style which was adapted to the fine white marble found in local quarries,” says Colvin.

Where the living come

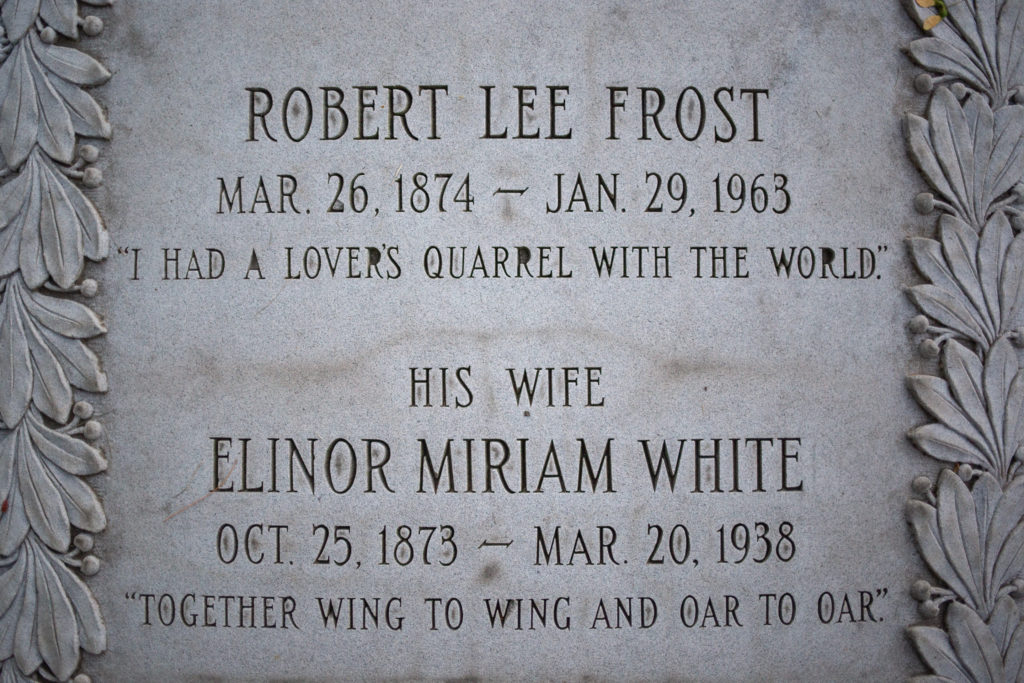

Tucked away in an unassuming corner of the cemetery is its most famous resident, Robert Frost. The poet died in Boston on January 29, 1963 and is buried in a family plot alongside his wife and children. In a cemetery full of artful stones, Frost’s simple, horizontal stone bordered by leaves is unremarkable. His mournful epitaph, “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world,” from his poem “The Lesson for Today,” is an understatement for the tragedies he endured in life.

His father died of tuberculosis when Frost was just 11, his daughter Irma was committed to a mental hospital, and his wife Elinor died 25 years before him. Of his six children, only two outlived him; Elinor Bettina only lived three days, Elliot died of cholera at age 4, Marjorie died of complications after childbirth, and Carol committed suicide when she was 38.

-

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

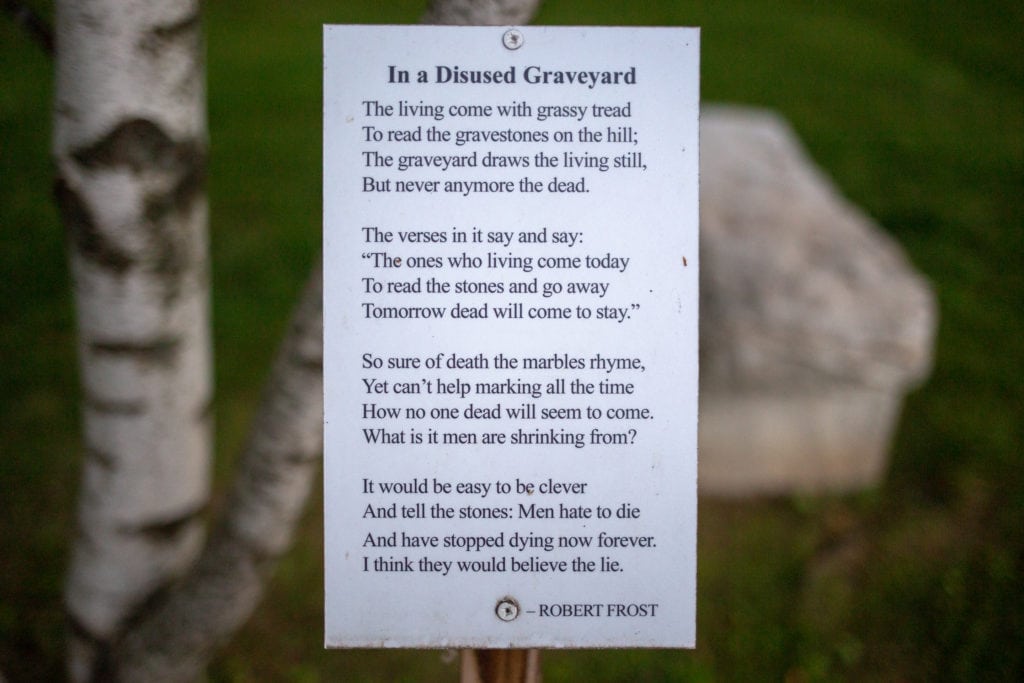

Printed on a sign nearby is another Frost poem, “In a Disused Graveyard,” which begins: “The living come with grassy tread / To read the gravestones on the hill / The graveyard draws the living still / But never anymore the dead.”

The dead may no longer come frequently to Bennington Centre Cemetery (the cemetery is still active, but those interested must be approved for membership before purchasing a site), but their markers are in remarkably good condition for their age; headstones in the front of the churchyard are as brilliantly white as the day they were carved. It’s not just the fresh mountain air that has kept the stones sparkling. Charles Dewey, the cemetery’s treasurer for thirty years, has been working for the past two summers to clean the stones. Those who like before-and-after makeover comparisons need look no further than the back half of the cemetery to see dark and dirty stones, patiently awaiting their turn with Dewey’s power washer.

The oldest headstone belongs to Bridget Harwood, who died in 1762. A widow, Harwood was the first settler to die in Bennington, just one year after she arrived from Massachusetts with her children. Reverend Jedidiah Dewey died in 1778, or rather, as his stone states, he “resigned his office in God’s temple for the sublime employment of immortality.” David Redding, a tory accused of helping out the British was convicted of “enemical acts,” and hanged. He is interred in a mass grave along with the soldiers from the Battle of Bennington; one side of the rectangular central monument reads simply “David Redding, Loyalist, Executed 1778.”

Dewey gave a walking tour this summer, but the cemetery doesn’t currently have a formal program in place for guided tours (visitors are free to explore on their own between dawn and dusk). An endowment established years ago helps offset maintenance costs, but the cemetery association welcomes all donations.

-

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

If you ever find yourself where two roads diverge in Southern Vermont, take the one less traveled by—especially if it takes you past Bennington Centre Cemetery. The cemetery requests that you don’t leave coins, pebbles, or plastic flowers when paying your respects to the state’s 1961 poet laureate, but visitors are gifted with these gentle words of warning directly from Frost himself: “The ones who living come today / To read the stones and go away / Tomorrow dead will come to stay.”

If you go

Visitors are free to explore the Bennington Centre Cemetery grounds on their own between dawn and dusk. The Old First Church is open Monday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Sundays 1 to 4 p.m.