In the middle of March, to slow the spread of COVID-19, Mayor Muriel Bowser closed restaurants, bars, movie theaters, and other non-essential businesses across Washington, D.C., indefinitely.

For nearly three months, the streets—largely devoid of tourists, office workers, and even residents—were eerily quiet. You could roll a bowling ball uninterrupted down the wide avenues named for concepts instrumental to the promises on which the U.S. was founded: along Constitution Avenue past shuttered Smithsonian museums; in front of the dark Departments of Agriculture, Energy, and Education on Independence Avenue; or down the Pennsylvania Avenue hill, a direct, diagonal line connecting the Capitol to the White House.

After George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis on May 25, the District sprung to life again—although perhaps not in ways anyone could have imagined during the previous weeks of stillness. More than a thousand miles southwest of where Floyd took his last breath, protestors donning face masks poured into the formerly-empty streets. Gatherings were largely peaceful, but after isolated incidents of violence and property destruction, a large fence was constructed around the White House and the neighboring Department of the Treasury.

Businesses boarded up their storefronts with fresh plywood. The city of gleaming white marble monuments became a blank canvas for people to express their outrage and grief. Statues were sprayed with messages of both despair and hope and the plywood was painted with colorful images of solidarity. Even the fence around Lafayette Square transformed overnight from a symbol of division into a community bulletin board filled with handmade posters, folded paper cranes, and other mementos of the growing movement.

The following are scenes from the first weekend in June, when Bowser officially designated 16th Street NW (which dead ends at Lafayette Square) “Black Lives Matter Plaza.”

The Washington, D.C., flag painted on 16th Street NW as part of a larger mural commissioned by Mayor Bowser.

Graffiti and a newly-erected fence outside the main Treasury Building, which is located next door to the White House at 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue.

The portion of 16th Street NW just north of the White House has officially been designated Black Lives Matter Plaza by Mayor Bowser. Street signs were installed early in the morning on June 5. The steeple of St. John’s Episcopal Church (known as the “Presidents’ Church”) rises in the background.

Crowds are kept away from the Capitol by Capitol Police, many of whom wear face masks.

Left/top: A crowd marches west along Constitution Avenue.

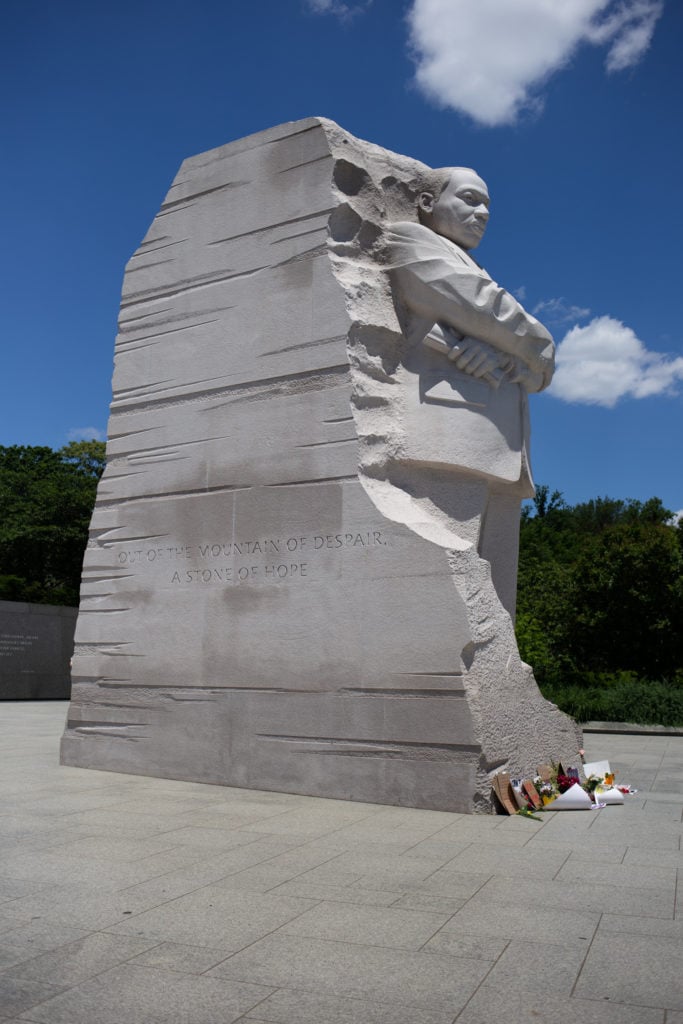

Right/bottom: The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, located in West Potomac Park next to the National Mall, is a frequent starting or ending point for demonstrations. Mementos are left at the foot of the granite statue.

Black activists give stirring, emotional speeches to a large crowd gathered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Face masks and handmade signs are ubiquitous with demonstrators.

A crowd takes a knee to listen to speeches near the Lincoln Memorial.

Graffiti at Freedom Plaza. The general mood is one of solidarity; on every corner people are passing out free snacks, water, face masks, and hand sanitizer.

The fence around Lafayette Square quickly became a de facto art gallery, with people contributing signs, artwork, and other memorabilia.

Early on Friday, June 5, the words “Black Lives Matter” were painted in bright yellow paint on 16th Street NW. The 50-foot-tall, all-caps statement was commissioned by Mayor Bowser and painted by staff from the District of Columbia Department of Public Works.

Left/top: A woman chants “Black lives matter” to a crowd assembled in the newly-named Black Lives Matter Plaza.

Right/bottom: Earl’s First Amendment Grill is just one of several stations that has sprung up around the city to feed and care for the crowds, free of charge.

White crosses fashioned from popsicle sticks bear the names of Black lives lost too soon to police violence. Simple epitaphs include “brother,” “father,” “a friend,” and “loved music.”

Demonstrators lie on the ground and chant “I can’t breathe” for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time Officer Derek Chauvin pressed his knee to Floyd’s neck.

A Black Lives Matter banner, blocking out the view of the White House, makes for a popular photo backdrop.