Coca-Cola’s slogan in the 1940s, “Where there’s Coke there’s hospitality,” still rings true today at the Bottleworks Hotel in Indianapolis, Indiana. The boutique hotel, housed in a former Coca-Cola bottling plant, recently underwent a painstaking restoration—but the end result was well worth the effort.

Despite being neglected for the better part of a century, the white terra-cotta facades and gold-plated signage still glimmer as the sun rises and sets over what was once one of the largest Coca-Cola bottling plants in the world. At the pinnacle of its success, more than two million bottles of the legendary soda pop paraded off the assembly lines each week inside of the iconic art deco buildings, situated at the north end of Massachusetts Avenue in downtown Indianapolis.

Today, after a 5-year restoration effort, the once parched Bottleworks District—as it is now known—is finally feeling refreshed. The district’s centerpiece, the glam Bottleworks Hotel, opened to guests in December, 2020, and is finding its rhythm as summer tourism begins to ramp up.

Terrazzo floors and gilded staircases

Built by local architectural firm Rubush and Hunter, the original facility was opened by the Yuncker family in 1931. No detail was spared—from terrazzo floors and ornate plaster ceilings to gilded staircases and intricate ceramic tile mosaics. “The art deco was a sign of the time, and the Yunckers were willing to put in the money on the front end so that people would buy into this grandeur that they were trying to showcase,” says General Manager Amy Isbell-Williams.

She explains how even the smallest features are a nod to the production of Coca-Cola’s signature soda: The grand staircase in the foyer resembles a soda fountain, the swirls in the plaster ceiling give the impression of fizz and bubbles, and the metal work replicates the recipe’s herbs and spices.

Even the ceramic tiles tell a story. Inside the luxurious lobby (formerly the tasting room) local ceramic artist Barbara Zech tells me about the tile work that stretches from floor to ceiling in the expansive space. “This room has a very unusual pattern,” she says, noting the work and research that went into decoding the meaning of the original motifs. The vertical green patterns are believed to mimic sugar cane. Zech points to the entrances: “If you look at the red tile that goes around the doors, they are supposed to be the shape of a bottle. And the little mosaics in the middle are supposed to be like bubbles.”

When Zech first saw the space, it had been boarded up and vacant for several years. She shows me where parts of the ceiling were caving in and where added ductwork left holes in the walls. I wonder how something so grand could fall into such disrepair. But after its mid-century heyday—and around the time metal cans first arrived on the beverage scene—the Yunckers’ glass bottling factory had gone flat.

Tony Hulman, then-owner of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, purchased the 12-acre facility in 1964 and used it to store his impressive collection of cars; the Coke factory moved to the nearby town of Speedway. Several years later, Indianapolis Public Schools bought the property, which served as a commercial kitchen, bus depot, and storage warehouse. The aesthetic form was disregarded in lieu of function.

“I don’t think they realized this would be revamped into such a swanky place,” says Zech.

Function and form

Zech, who grew up in Indianapolis and graduated from Herron School of Art, has spent the past 25 years honing her skills as a ceramicist. While her projects include functional and fine art, she spends a lot of her time doing historic tile preservation. She is a featured contractor with Indiana Landmarks, which is how she found herself working on the Bottleworks projects, the largest restoration she has completed to date. The lobby alone required more than 800 new handmade tiles to replace the damaged pieces.

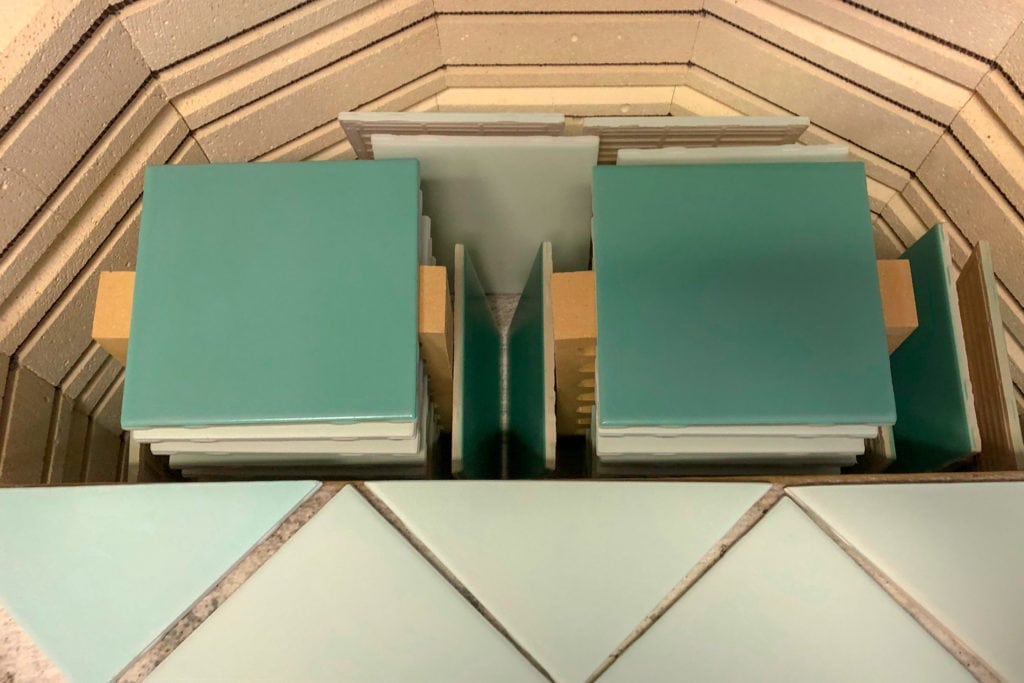

“There are five different colors of glazes here in the lobby,” Zech says, adding that each glaze is a different sheen—some with a matte finish, others satin or glossy—which all had to be taken into account when color matching. She also had to consider the way the original tiles had faded and become discolored by the bottling process and ambient cigarette smoke over the years.

“It was quite a process,” she says. “Some of the colors in here took as many as eight layers, with base coats, underglaze, and clear coat before being fired in the kiln.” Before running large batches in her full-sized kiln (which holds around 50 tiles), Zech used a small test kiln in her studio, firing only six tiles at a time, in order to test the different colors and combinations for approval.

To say the project was massive would be an understatement. “It consumed me,” says Zech. In addition to the lobby, she also replaced tiles in the upstairs laboratory and recreated narrow tiles with a checkered pattern that march up the grand spiral staircase and down the executive hallway between the travertine marble walls. Since the originals were factory made with the pattern screen printed on, Zech decided to scan the pattern and use glaze decals instead of painstakingly hand-painting each one.

Santarossa Mosaic and Tile—the same local business that installed more than 70,000 square feet of terrazzo products here during the 1930s and ‘50s—joined the effort once again, installing Zech’s restored tiles and completing tile work in the new hotel rooms.

Embracing history

Zech’s hands-on contribution making and glazing tiles took nearly 8 months, but she is quick to acknowledge that her work was just one small part of a much larger team effort. She loves being a part of the Bottleworks story and helping to keep the history alive. “It’s an honor to have a hand in this process for sure,” she says.

Isbell-Williams calls the project an amazing transformation, especially considering many of the developers that bid on the campus wanted to raze the buildings and start anew. But the adaptive reuse plan submitted by Hendricks Commercial Properties ended up securing the contract.

“I think that just goes to tell you that the city was eager to see what someone could do with this architectural gift that we were given,” she says. “It speaks volumes to the city and to travelers and what they want from this project—they wanted us to embrace the history and that’s what we are here to do.”

If you go

The Bottleworks Hotel offers a boutique experience with 139 unique rooms occupying the second and third floors of the historic building. Everyone on staff is personally trained by Indiana Landmarks to tell the history of Bottleworks.