As I step out of the heavy summer heat and push through a set of revolving doors, I’m met with a blast of controlled AC. I feel as if I’ve gone through a portal into not just another climate, but a completely different decade. The lobby of the Chicago Motor Club has tall, peach-colored walls and is filled with a soft, golden light—it resembles some sort of transportation hub, like an old train station.

The original 1928 terrazzo floor beneath me is laid out in long, contrasting strips of dull white and deep, gray-green. Even the plush chairs and smooth tables look retro. True to the spirit of 1920s art deco, everything is very angular and symmetrical.

I notice something else—the space is very quiet. There are muffled whispers here and there from a few people scattered among the chairs, but the noise from the traffic outside doesn’t seem to penetrate the high, thick walls. Like a library, the silence only adds to the lobby’s dreamlike atmosphere.

Directly in front of me is an elaborate, silver balcony decorated with geometric and floral motifs. Similar details are employed throughout the building—on the ceiling trim, around the elevators, and in the vents on the floor. But what’s so extraordinary about the balcony is not what adorns it, but what sits on top of it. Gazing down at the comings and goings of the lobby is an original 1928 Ford Model A—a true homage to the history of the building and Chicago’s unique automotive past.

Leading by example

To the outside world, Chicago may be known less for its automotive history than for its architectural masterpieces. But the city’s central location between coasts—and its close proximity to Detroit, the Automobile Capital of the World—made Chicago an important player in the early promotion of the automobile.

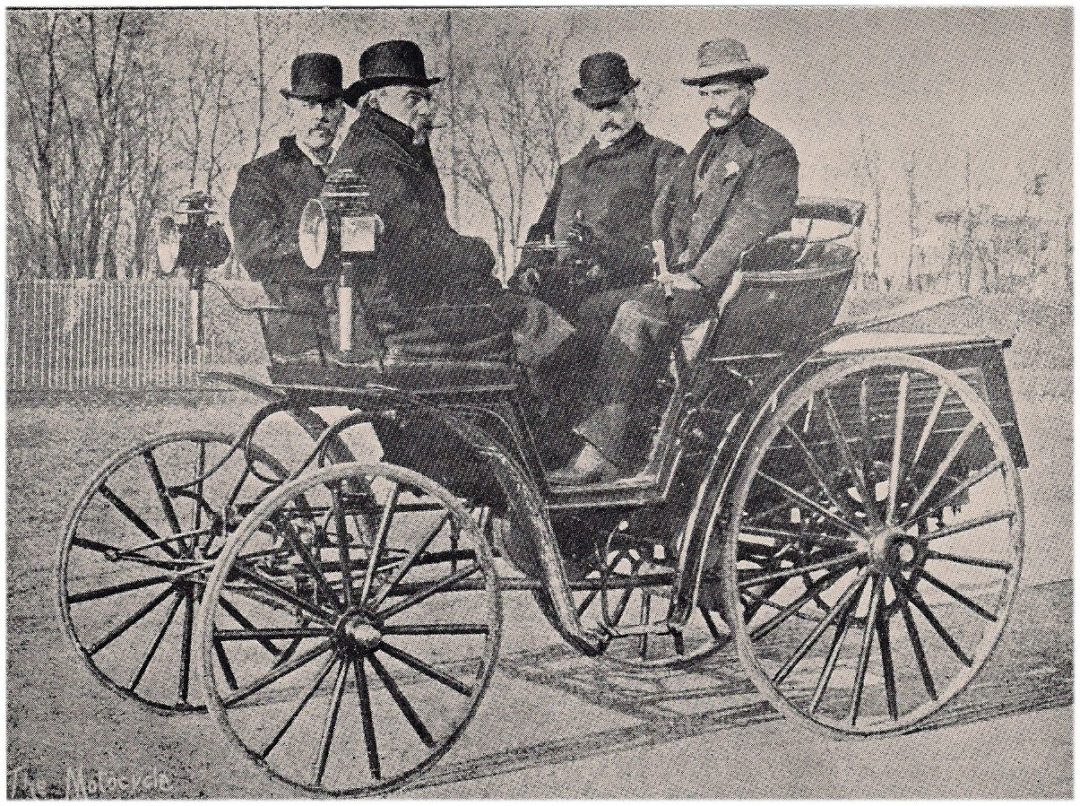

The first automobile—which was essentially a gas-powered, horseless carriage—appeared in Chicago in 1892. Three years later, on Thanksgiving Day in 1895, the Chicago Herald staged “America’s First Automobile Race,” a well-publicized event that ran from Chicago’s Jackson Park up to the neighboring town of Evanston. The winner of the race completed the 52-mile round-trip loop in just under eight hours, driving at an average pace of six miles per hour. And In 1901, in an effort to highlight new car models, the first Chicago Automobile Show was held—today, it’s the largest and longest running auto show in North America.

At the start of the 1900s, excitement surrounding new automobiles was high and avid motorists began to organize “motor clubs.” The clubs—whose members were almost exclusively white men—would gather to plan races, discuss new models, and generally fraternize. But unlike many of the 50 other motor clubs that formed across the United States in 1906, the Chicago Motor Club was less of a social group and more of an advocacy union.

From its outset, members of the Chicago Motor Club sought to distinguish themselves by advocating for both automobile ownership as well as safer road conditions and better traffic flow. The club even had a profound impact on how the city of Chicago planned and improved its central business district. These improvements included the widening of streets, the addition of more restricted parking, and implementing traffic control signals. After hearing about the Chicago club’s impact, other groups across the country—including the very well-known American Automobile Association (AAA)—quickly began to adopt a similar focus.

How do you house 70,000 members?

Good news travels fast, and by the mid 1920s, the Chicago Motor Club’s membership had surpassed 70,000 people. Charles Hayes, the president of the club at the time, wanted to honor such an achievement and decided that both the members and the various departments within the club—law, mechanical, and claims—needed a proper place to congregate.

On January 28, 1929, just 265 days after receiving approval to build, the brand new Chicago Motor Club headquarters opened to the public. Located on the north side of East Wacker Place, the site was specifically chosen due to its prominent location near Michigan Avenue—the street where most auto-related businesses were housed.

“At the grand opening, the Chicago Tribune described the new building as ‘a monument to the progress of motordom.'”

Designed by Chicago architectural firm Holabird and Root, the Chicago Motor Club was built from gray limestone and dominated by a highly-decorative, cast-iron frame that outlined the main entrance. The club’s name, Roman numerals noting the date of construction, and the club’s logo—a large “C” encircling a star—were carved into a stone block to the right of the entrance.

Most of the floors inside the building contained office spaces, with each department occupying its own floor. But the real attraction was the lobby, which housed the touring bureau of the Chicago Motor Club. Here, visitors could collect maps, travel itineraries, and hotel guides. The club also offered something called TripTiks, maps that included tips on where to eat, what to see, and where to stay along the highway. As they sat and planned their journeys, guests could enjoy a drink from the fender-shaped, mahogany bar. During Prohibition, bartenders at the Chicago Motor Club are rumored to have served glasses of “Giggle Water”—a code name for alcohol.

At the grand opening, the Chicago Tribune described the new building as “a monument to the progress of motordom.” Today, the building is still regarded as one of the finest examples of art deco-style architecture in the city of Chicago.

Past and present in one space

The Chicago Motor Club hasn’t always had such a glamorous past. Driven by the need to save money and space, the club relocated its headquarters to De Plaines, Illinois in 1986 and the beautiful art deco skyscraper sat vacant for 28 years.

However, in 2014, a group led by John Murphy, the president of MB Real Estate Services, bought the Chicago Motor Club building for $9.5 million. Murphy and his team made a point to maintain and restore as much of the original building as possible, including the flooring, light fixtures, and a massive, 29-foot mural painted above the elevators.

The mural, created by renowned muralist John Warner Nortin in 1928, depicts a map of the United States, including all of the national parks and major cross-country highways present at the time. When the Chicago Motor Club building opened, the map helped provide inspiration for its visitors, who could study the mural and plan their next road trip.

After the 2014 restoration, the Chicago Motor Club reopened as a Hampton Inn hotel on July 10, 2015. This reopening is just one example in a long list of historic Chicago places that have recently been transformed into lodging. Chicago is making a city-wide effort to turn some of its most historic buildings into modern hotels, giving guests a unique taste of the city’s past and present in the same space. Other buildings that have gone through a similar process include the Old Dearborn Bank Building, which is now a Virgin Hotel, and the Londonhouse Chicago, which was transformed from an insurance firm into an upscale, boutique hotel.

A new kind of traveler

Many hotel guests might not be aware of the Chicago Motor Club’s historical significance. The woman working the front desk tells me that most people who stay at the hotel do so for its location and proximity to many attractions—not for its illustrious place in the history of the automobile. Even so, she hands me a printed pamphlet that shares some history about the building (the back of which features a long list of “restaurants within walking distance”).

Taking a look around, I see people waiting with their luggage—some of them are reading, others are passing time with a (legal) glass of Giggle Water at the bar—and I’d like to think that this scene is identical to what guests of the club might’ve found 90 years ago. Although this beautifully vaulted lobby now serves as the entrance for hotel guests, I’m glad it’s still welcoming travelers, even if they’re simply arriving at their destination and not coming to plan it.

If you go

The Chicago Motor Club (now called the Chicago Motor Club Hampton Inn) is open all day, seven days a week. You can book a room online, or simply stop by and check out the stunning lobby. And you can still order Giggle Water at Jack’s Place, the bar located right inside the lobby.