No one knows exactly how a herd of feral ponies got to Assateague Island, but my favorite story goes like this: Once upon a time, back when ocean fog and howling winds spelled doom for ships sailing along the East Coast of the United States, a Spanish galleon carrying a cargo of horses collided with the shore. The ship didn’t make it but the ponies did, swimming to safety on the sandy land mass that shimmies down the northern end of Delmarva’s (Delaware-Maryland-Virginia) eastern peninsula.

Assateague, a 37-mile-long barrier island, is a harsh mistress. But for at least 200 years, the ponies have survived, living hoof deep in saltwater marshes, swarmed with mosquitoes and exposed to the elements. Because it is an island, there’s only one way to escape from Assateague: by swimming.

As Assateauge is uninhabited by people, the closest community lives across the strait on Chincoteague Island. In 1925, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company seized on the idea of swimming ponies, resurrecting a 19th-century tradition that had fallen out of favor. The plan was to round up the feral horses across the channel between the islands of Assateague and Chincoteague and sell them to the highest bidder. The money earned from the auction would go back to the fire department which, after contending with a rash of fires that decimated the small town’s core, desperately needed new equipment.

At that first modern Pony Penning and carnival, 15 ponies swam across the channel. This week, over 100 will make the journey.

“The day of the swim is like Christmas morning to us,” says Denise Bowden, a member of the Pony Committee and a 28-year veteran of the Saltwater Cowboys, the horseback riders who herd the ponies and accompany them across the channel. “The locals live for this week. It’s our source of pride, our traditions, our everything.”

The ponies, officially called Chincoteague Ponies, used to freely roam Assateague Island National Seashore, walking among visitors and strolling the endless beach. Today, miles of fencing keeps humans and the herd apart.

Out in the vivid green marshes, small groups of palominos, bays, and white-and-brown pintos graze. Foals in all different shades of browns and golds frolick among the herd, their gangly legs too long, their movements awkward and spastic.

Around 70 colts and fillies are born each year in this grassy swamp. Because they feed on saltwater cordgrass and drink twice as much freshwater as the average horse to compensate, even the little ones have bellies that are bloated and round.

A horse girl’s heaven

I visit the island a few weeks before the Pony Penning, when just under 150 ponies will swim across the channel. The foals that are too small to safely swim will be trucked across the causeway with their mothers to the annual event.

Almost as soon as the Pony Penning began, thousands of people were descending on Chincoteague annually for the July carnival. But it was in 1947, with the publication of the children’s book Misty of Chincoteague, that the event rose to international fame.

On a visit to Chincoteague in 1945, author Marguerite Henry fell in love with Misty, a white-and-chestnut pinto foal that lived on a local ranch. Henry arranged to have the filly shipped to her home in Wayne, Illinois where she penned her bestselling story.

Ten years later, Henry returned the now-pregnant Misty to Chincoteague to give birth to her foal, Stormy (Chincoteague ponies are traditionally named after weather events at the time of their birth). The new baby was the subject of Stormy, Misty’s Foal, one of many sequels to the original Misty story. Together with the 1961 film of the same name, Misty not only brought new attention to the Pony Penning, it inspired generations of horse lovers.

I’m taking a break from pony watching, feet buried in the warm Assateague sand, the Atlantic in my ears, when I get a text from Leila, a friend who grew up in Virginia. “I’m actually in your homeland right now, in Chincoteague,” I tell her. She’s immediately floored. For us erstwhile preteen horse-lovers, this island is the stuff of our pony-frolicking dreams.

“Did you visit the former stalls of Misty and Stormy?” she asks. “I have a piece of horse hair from those stalls in my scrapbook!”

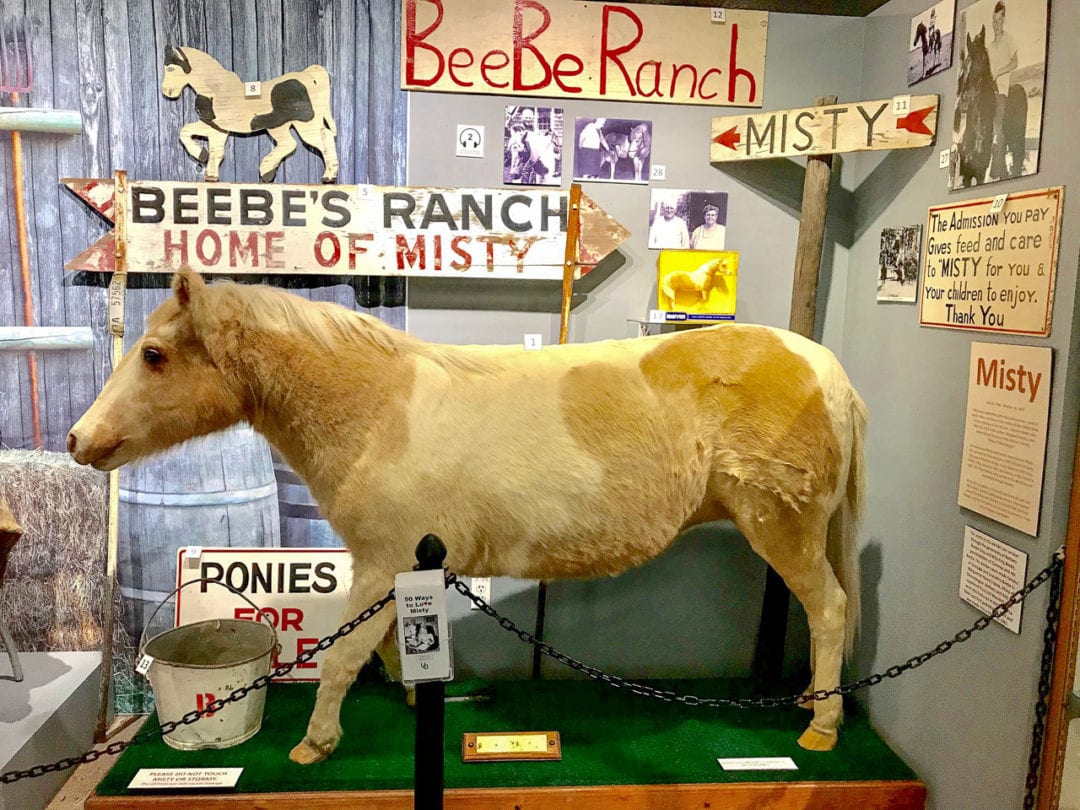

I laugh out loud at her reply, not because the idea of visiting the stalls of famous ponies is ridiculous—but because it’s not. When, later, I visit the Museum of Chincoteague, it’s for one reason only: to see the final resting place of Misty and Stormy. Inside, the taxidermied husks of both ponies are surrounded by memorabilia from their remarkable lives.

A generational journey

Though it sounds dangerous, the Chincoteague ponies are actually good swimmers. “In 93 years, we have never lost a pony during the swim,” Bowden says. “They are very natural about it and they do it all the time on their own.”

The day of the event, 45 Saltwater Cowboys accompany the herd across the channel. The group is made up of people from the fire department, many of whom inherited their positions from their fathers or grandfathers. Bowden was the first woman to join the riders.

“When I look into their eyes, I feel I can see their souls and all the freedom that comes with them out there running wild.”

All in all, the swim takes only about four and a half minutes. They wait for slack tide—the 20-minute period between high and low tide—when the water is still and sometimes so shallow that the horses’ hooves can almost touch the ground. Fire department personnel ride in boats alongside the swimmers to closely monitor for any ponies in distress.

“There’s such a magical feeling about being out there with [the ponies],” Bowden says. “I wonder what’s going through their minds. When I look into their eyes, I feel I can see their souls and all the freedom that comes with them out there running wild. Nothing like it in the whole world.”

Photos of the swimming ponies are everywhere on Chincoteague. Dozens of velvety muzzles poking just above the waterline, nostrils flaring. I’m desperate to get closer to them than the fence-line allows so when I find out that there are ponies penned in the corrals behind the McDonald’s, it’s all I can do to contain my excitement.

These ponies belong to someone but they’re Chincoteague through-and-through and when I stop by the next day to see them, I discover a tiny foal with blue eyes and a scruffy white mane and tail frolicking next to its buckskin mama. Just a few days old, this little one is so out of proportion he has to splay his legs out wide to eat the grass at his feet. Though there’s at least 70 years between them, it’s uncanny just how much this baby looks like the bronze statue of a young Misty enshrined on Chincoteague’s Main Street.

The smallest of the small from the wild herd, foals like this spindly baby, won’t be sold at auction this year. Many of the ponies, in fact, are making the journey to Chincoteague simply because it’s easier to keep the herd together than to separate out the individuals destined to begin new lives off their native island. At the end of Pony Penning week, the remaining horses will be returned to Assateague where they’ll go on to replenish the herd with a new season of babies.

A few days after leaving Chincoteague, I get another text from my friend Leila. It’s a photo of a sepia-toned page from a scrapbook. Three strands of brown horse hair are taped to the top left-hand corner. Next to it, she’s written in her 11-year-old scrawl: “A hair from the real Foggy Mist, Stormy’s baby.”

I never did make it to the sacred stalls of Misty and her kin—restricted opening hours foiled my attempts—but for a recovering horse-fanatic like me, these paired islands of Assateague and Chincoteague are hallowed ground in and of themselves. Though their pony veneration may be less emphatic, the wild horses are no less important to Bowden and the people of Chincoteague. “It’s our way of life,” she says, “and it’s centered around the ponies.”

If you go

Due to COVID-19, the Chincoteague Fire Department has cancelled the 2020 Pony Swim and related events.