Just over 100 miles north of Des Moines, Iowa, sits the small town of Clear Lake. The large, eponymous lake is an obvious dream for fishers. But since February 3, 1959—famously dubbed “the day the music died”—the city of Clear Lake has also become a mecca for lovers of classic rock and roll.

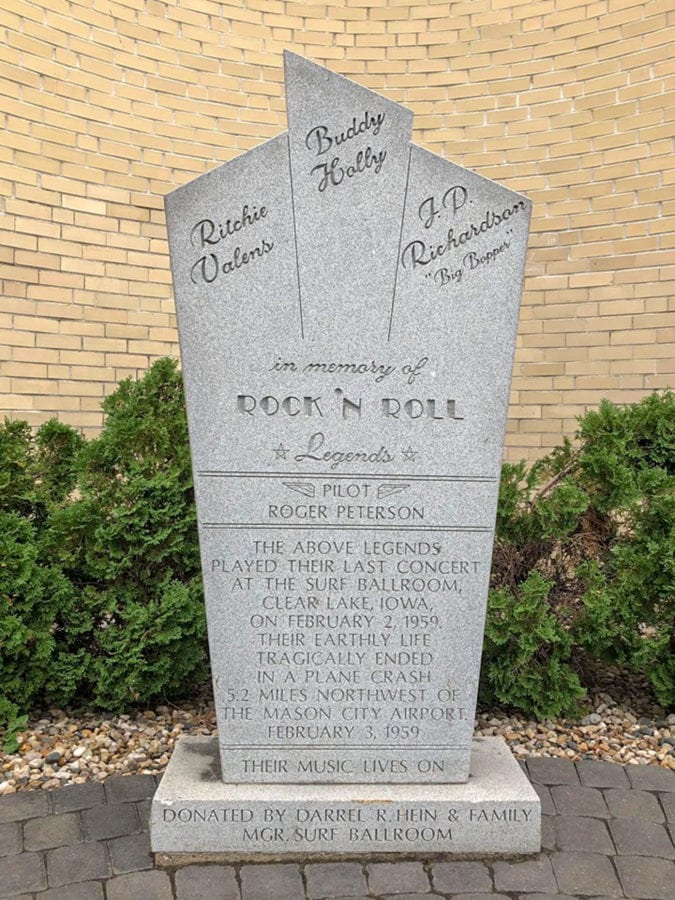

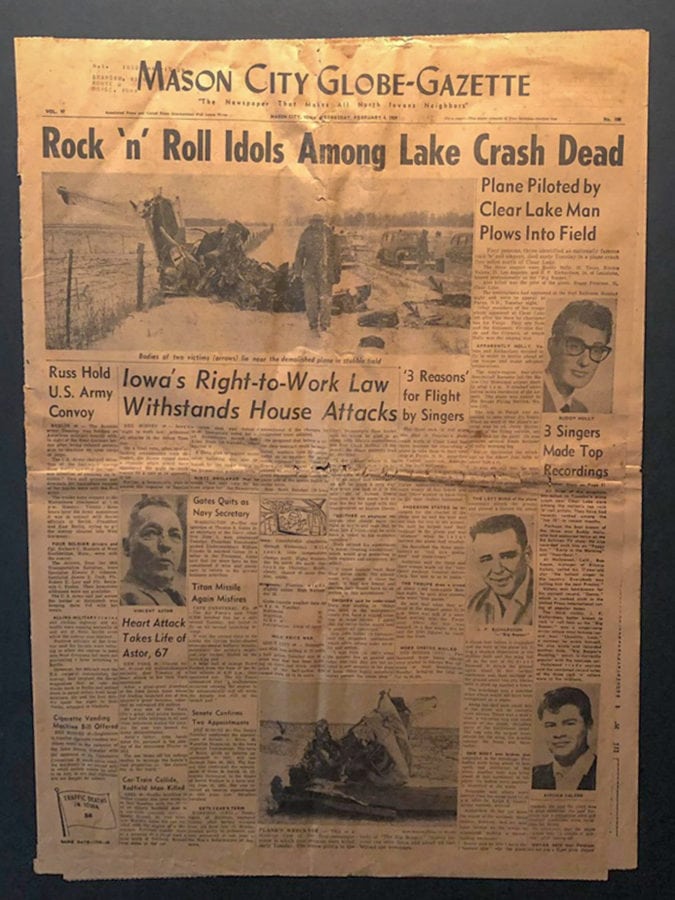

It’s been 60 years since the Surf Ballroom held its now-infamous Winter Dance Party, where Buddy Holly, JP “The Big Bopper” Richardson, and Ritchie Valens played their last show for an adoring crowd. They died just hours after the show ended, when their plane crashed into a field located outside of Clear Lake.

As I, a self-proclaimed music nerd, approach the town of Clear Lake, a playlist featuring hits by Holly, Richardson, and Valens sets the scene. I feel as if I’m driving into not just another city, but back in time to a different decade.

-

In 1959, the Surf Ballroom held its now-infamous Winter Dance Party. | Photo: Jessi Haish LaRue -

The marquee of the Surf Ballroom. | Photo: Jessi Haish LaRue

The Surf Ballroom

The streets surrounding the Surf Ballroom and Museum are named for Holly, Richardson, and Valens. The marquee outside reads, “The music lives on; Welcome rock & roll fans to the legendary Surf Ballroom.” There’s no admission charge for a self-guided tour, but donations are encouraged and go toward preserving the historic building.

As I step onto the hardwood dance floor, I can feel the history swirl around me: the music, the memories, and, of course, the dancing. Booths toward the back, once occupied by women in poodle skirts, have small drawers to stash personal items—or alcohol, when it was prohibited at the Surf.

Laurie Lietz, executive director of the Surf Ballroom, says visiting the historic performance venue is a “bucket list item” for many people. Although many museum visitors have clear memories of “the first big music tragedy,” people of all ages make a pilgrimage to the famed ballroom to hear stories of its legendary performances.

“There’s nothing like it,” Lietz says.

The walls of the dressing room next to the stage are adorned with hundreds of performers’ autographs. Don McLean, who immortalized “the day the music died” line in his 1972 hit American Pie scrawled a portion of its lyrics on a wall here in 1994.

By the time they played their final show, Holly had already made his mark on rock and roll history. Richardson and the 17-year-old Valens were rapidly rising stars. The ballroom’s bar area combines the past and the present, featuring photos and guitars from recent performers, as well as memorabilia from the three that were lost on that fateful day.

Parting words

The Winter Dance Party tour of 1959 had been fraught with trouble: The show dates were spread all around the Midwest, where the winter weather was harsh. The musicians traveled from one city to the next in a bus that broke down frequently, and flu and frostbite ran rampant among the tour’s musicians and crew.

After the Surf Ballroom show, Holly was fed up. He chartered a small plane for himself and his bandmates, Waylon Jennings and Tommy Allsup, to take them to their next show in Moorhead, Minnesota. But before the night was over, Valens flipped a coin with Allsup in the ballroom’s green room, winning his seat. Richardson, who had the flu, took Jennings’ seat. Holly, Richardson, and Valens boarded the plane with pilot Roger Peterson in Mason City, just outside of Clear Lake.

Allegedly, Holly’s parting words to Jennings were, “I hope your bus freezes up.” Jennings replied, “I hope your plane crashes.”

Although the exact cause was never determined, it is thought that poor weather conditions caused the plane to crash in a farmer’s field just outside of Clear Lake. The town—and rock and roll—was changed forever.

The crash site

I drive down a gravel road on Gull Avenue, looking for the unofficial crash site marker created by a local artist: a simple pair of black, horn-rimmed glasses, modeled after the ones Holly wore. But before I see the glasses, I notice a small group of cars parked alongside the quiet country road displaying license plates from Iowa, Massachusetts, and Minnesota. Their owners are paying their respects to the three musicians.

Libbey Hohn, director of tourism for the Clear Lake Area Chamber of Commerce, says the lack of directional signage is purposeful.

“It is part of our history,” she says. “We try not to exploit the tragedy … but rather honor their legacies by keeping live music not only at the forefront of the tribute, but also with the mission of the North Iowa Cultural Center and Museum, the non-profit that was formed to preserve, maintain, and manage the Surf Ballroom.”

After taking a photo with the marker, I make the somber half-mile trek to the center of the field, following the beaten down grass path. As I pass others making their way out, we acknowledge each other with a silent, solemn head nod.

The memorial itself is simple but poignant. A small monument features a metal guitar inscribed with the musicians’ names and records displaying their hit singles. A monument for the pilot is located just a few feet to the side. Fans have left sunglasses, flowers, costume jewelry, hair scrunchies, and other mementos. A metal-stamped sign from the property owners urges visitors to “Show your respect; carry out your trash.”

-

The memorial itself is simple but poignant. | Photo: Jessi Haish LaRue -

A pair of black, horn rimmed glasses, modeled after the ones Holly wore. | Photo: Jessi Haish LaRue -

A photo of Valens at the crash site. | Photo: Jessi Haish LaRue -

A memorial to the pilot of the plane. | Photo: Jessi Haish LaRue

A memorial art piece located near the Surf Ballroom features vinyl records by Holly, Valens, and Richardson in the ready-to-play position. Visitors can push buttons to hear song clips and biographies of the three men. Their music seems to travel through the streets and decades, floating in the direction of the Surf.

“There is something about ‘50s music that transcends all generations—and that is what our community celebrates,” Hohn says.

If you go

The Surf Ballroom is open Monday through Friday year round, and weekends between Memorial Day and Labor Day.