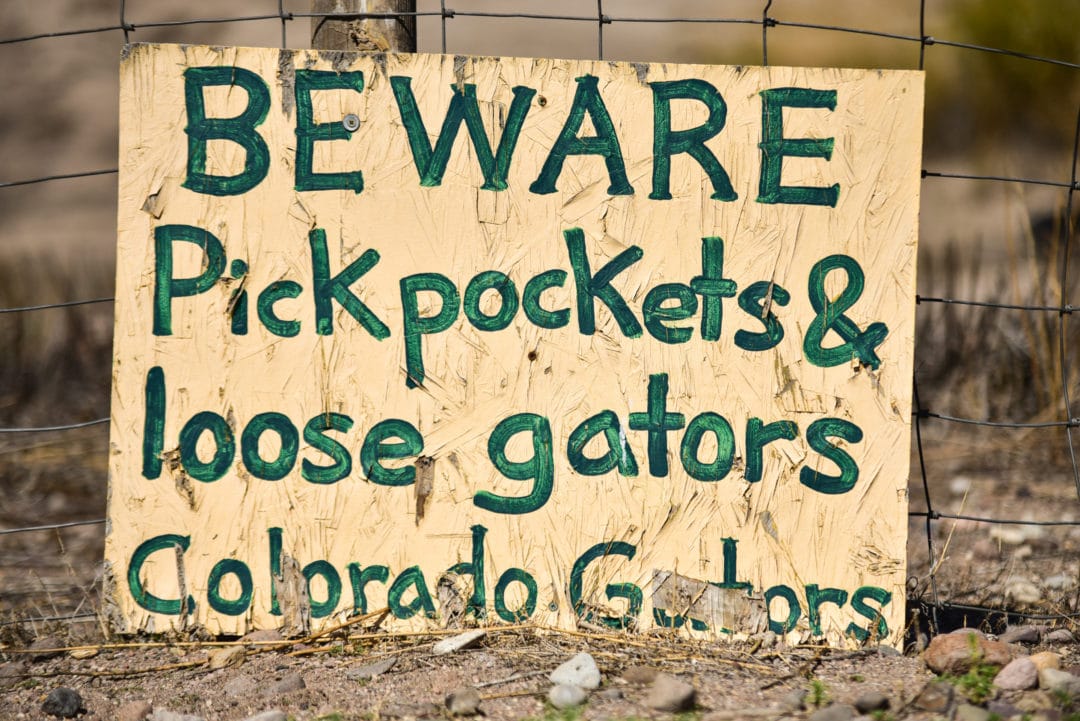

Let’s start with the elephant in the room—or, rather, the 900-pound alligator soaking in a pool of murky, shallow water 10 feet from where I stand. “That’s Bruce Almighty,” says Erin Young, co-owner of Colorado Gators Reptile Park, pointing to an open patch between dense marsh reeds. “Bruce is the biggest gator we have here.”

The sun is beating down on us but there’s enough of a morning breeze here, just outside of Mosca in south central Colorado, to keep us cool for the moment. My eyes fixate on Bruce—a mesmerizing and formidable creature who looks like an armor-plated tank ready to strike. Half of his body sits above the water showing off just enough girth and a powerful tail to prove his dominance. His hind legs hang like thick, webbed canoe paddles and he’s about as long as my car—13 feet, according to Young—and wider than the backseat.

“We picked him up from another fish farm up in Idaho,” says Young. “He’s grown since then and is the largest alligator in the West. I think he could use a bit of a diet, though.”

We laugh, but my eyes remain locked on Bruce. I’ve seen enough reruns of The Crocodile Hunter to know that one false step could lead to a missing limb. But we are safely behind a fence and Bruce seems content simply lounging in the warm sun.

Roadside oasis

Colorado Gators Reptile Park is a roadside oasis in the high desert of the San Luis Valley, four hours south of Denver. Founders Lynne and Erwin Young moved here with their four children from Texas in 1974. Intending to utilize the valley’s geothermal water resources to grow tilapia, they bought 80 acres. At first, there were no alligators, just fish. But after filleting the fish, the guts and carcasses needed to go somewhere. In 1987, the Youngs purchased 100 baby alligators to help them dispose of their leftovers. With plenty to eat and the well pumping 87-degree Fahrenheit water into pools for them to soak in, the alligators thrived. So did the local interest.

“We had power line workers who saw the gators from their cherry pickers,” Erin Young says. “Well, then people in the area wanted to see them, too, so we started doing small tours. That was 1990 and we’ve been doing it ever since.”

Come for the gators

My visit to the park begins with a warm welcome from resident tortoises, each weighing well over 20 pounds. I keep my distance when the staff brings out a slithering yellow and white Burmese python and a tarantula the size of my face. But when one of them produces a baby alligator to hold, I can’t resist.

Today, the park remains a working fish farm where visitors can tour the tanks and feed the fish but also cast for a tasty dinner with a paid admission. If you catch a carp, you will be asked to feed it to the alligators. And that’s why, as Young tells me, “We get anywhere from 30,000 to 40,000 people a year.” They come for the gators.

Every visitor has the chance to get an up-close view of what is, essentially, a living dinosaur. For those brave enough, gator wrestling classes are offered.

“Most of the alligators are pretty docile and the classes help when we need to administer medicine or move them to another location,” Young says. “At the same time, we’re educating people about safe handling and how they aren’t meant to be pets.”

Over the years, Colorado Gators has also become one of the few alligator rescues outside of Florida or Texas. More than half of the park’s 300 alligators have been confiscated from private owners. In one of the larger enclosures, reptilian bodies sprawl in the dirt. Others float in the pond with only their lumpy spikes and beady eyes peeking out above the water. “Two hundred of them are rescues,” Young says.

In addition to the alligators, the park is home to other illegal or unwanted exotic former pets including Nile crocodiles, tortoises, lizards, emus, iguanas, and pythons. “People tend to forget they grow up and can be dangerous,” Young says. “Not to mention expensive to feed. We’ve had people show up, drop them off, and leave plenty of times.”

Sun and solitude

Morris, an alligator famous for eating Chubb’s hand in the Adam Sandler movie Happy Gilmore, spent 30 years in the movie industry and now doesn’t care much for cameras.

Young peeks over the fence to say hi to Morris. “Most of our gators can tell the difference between a camera and a catch rope, so when you raise the camera, they don’t care,” she says. “Except for Morris here. He can be pretty aggressive about it.”

Just past Bruce, who is still enjoying the sun and morning solitude, I sit along a platform perched above one of the ponds. Here, the full park comes into view; a swampy anomaly in an otherwise dry valley far from any major cities.

Families and a busload of children begin shuffling toward the gift shop. As Young heads to the counter to help check people in, I circle back around to spend time with the park’s rare albino alligators. A father and son look on, equally interested in their unique appearance. Children feed grass to a few tortoises and others watch in amazement when the snakes come out. I move on, wondering who is actually watching whom.

If you go

Colorado Gators Reptile Park is open daily between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.