Historic Congressional Cemetery may have been the first national burying ground in the U.S.—predating Arlington by at least 50 years—but today it is full of life.

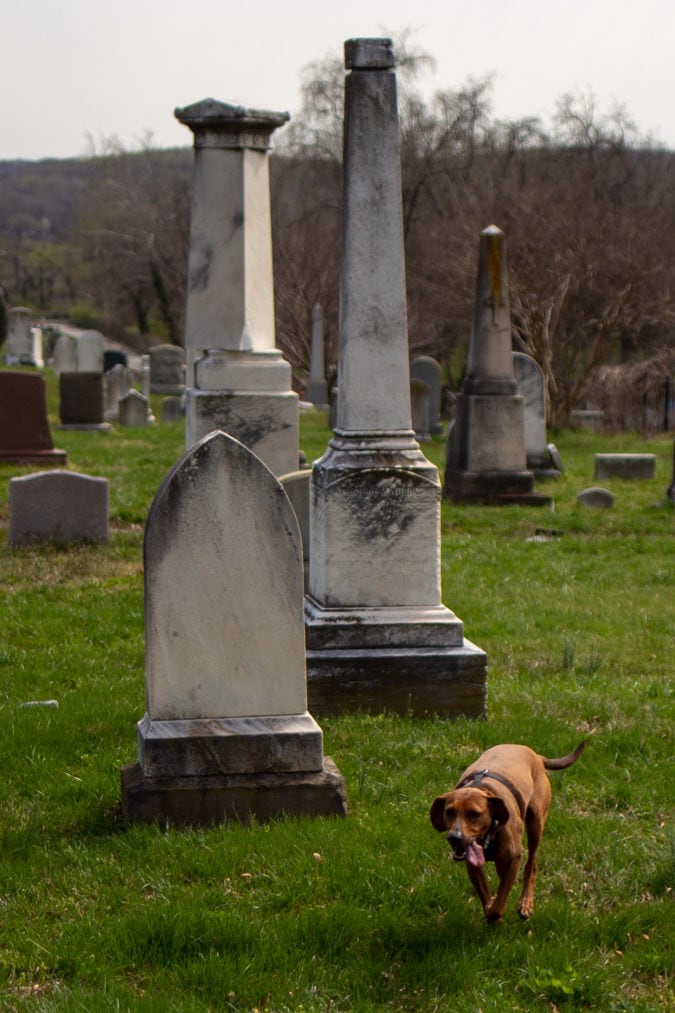

Located just a few miles east of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the cemetery is predictably the final resting place of countless notable and historical figures. But depending on when you visit, you may also encounter dogs darting in between the headstones and find goats grazing in the grass or doing yoga.

Although cemeteries may seem as if they’re made for the dead, memorials to dearly departed loved ones are actually for the benefit of the living. In the later half of the 19th century, when the rural cemetery movement pushed burial grounds to the outskirts of town, expansive, beautifully landscaped cemeteries soon became popular places to take dates or have weekend picnics.

Congressional Cemetery, founded in 1807, was the first national burying ground. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan These monuments mark the graves of—or just memorialize—members of Congress. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan The cemetery hosts a wide variety of events, including a book club. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Congressional Cemetery is following the lead of other once-neglected cemeteries hoping to renew the public’s interest in preserving historic burial grounds. While the Victorians were obsessed with death, the new trend in cemetery programming revolves around the living. Congressional hosts movie nights, book club discussions, and, yes, even picnics.

“Congressional Cemetery is full of life, which sounds like a contradiction when you’re speaking about the final resting place for over 65,000 people,” says Lauren Maloy, Congressional Cemetery’s program director. “Having a group of people who care about the cemetery means much more than having a sequestered cemetery isolated from the living.”

Dogs among the dead

Congressional Cemetery not only welcomes humans, but also their dogs. One-fourth of the operating income comes from donations made by members of the popular K9 Corps program. In addition to dog-walking privileges, approximately 600 households—and their 770 dogs—can participate in spring “Yappy Hours,” take photos with Santa, and attend the Blessing of the Animals ceremony.

Water bowls are placed around the cemetery for the dogs. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Dog-walking privileges are available to members of the K9 Corps during posted hours. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Oskar Hamilton, a scruffy terrier mutt, and his human, Courtney Williams, have been members of the K9 Corps since 2016. They joined the waitlist before they even lived near the cemetery, and when Williams heard that they’d finally secured a spot in the coveted corps, she says she “very much felt like a proud mom whose son had been admitted to a selective educational program.” They now live within walking distance and visit every other day.

The cemetery staff is quick to point out that they are not a dog park, and stress that dog walking is a privilege limited to members of the K9 Corps. Members must abide by the schedule and a list of rules, but nonetheless the program is so popular that there is often a two-to-three-year wait for the more than 400 people—and their pups—on the waitlist to become members.

The base membership fee is a tax-deductible donation of $235, in addition to an eight-hour volunteer commitment. The maximum number of dogs allowed on any account is three, and membership is non-transferable. For those unwilling to wait—or if you’re just visiting—day passes are available for $10.

Beverly Hallberg and her three-year-old English bulldog, Dray, go on walks in the cemetery in the fall and spring when the daytime heat is manageable for Dray. “Congressional Cemetery is a place of respite in the very busy city of D.C.,” Hallberg says. “I’ve yet to meet one person who’s been who hasn’t loved it.”

Pups and preservation

Respect for the grounds and its visitors is the number one rule of the K9 Corps. While allowing dogs into a burial ground packed with hundreds of thousands of bones may seem like a bad idea, the joy that the pups bring to the historic grounds is palpable.

“For the most part, reaction to the K9 Corps from the community is overwhelmingly positive,” says Maloy. “The dog-walking program brings life and vitality to the cemetery. Moreover, the dog walkers contribute hundreds of volunteer hours that contribute to the preservation of the National Landmark.”

It wouldn’t be a D.C. cemetery without some cherry blossoms. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Congressional Cemetery is the final resting place for more than 65,000 people. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan “A lingering complaint.” | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The K9 Corps program began in the early 1990s when the cemetery had fallen into disrepair—the grass was waist-high, headstones were broken, and the neighborhood was unsafe. A local group of dog walkers recruited others and eventually founded a formal club, beginning with just 50 members. Just the mere presence of dogs—and their watchful owners—makes the cemetery a safer place and the K9 Corps ensures that there is always someone around to sniff out trouble. As a result, Congressional Cemetery now claims to be “mostly free and clear of riff raff and vandals.”

Dogs have been used to comfort people in times of tragedy and trauma, but the peaceful landscape of Congressional Cemetery has a calming effect on the dogs, too. Hallberg says that Dray is “a sweetheart with people and dogs he knows, but he has some irrational stranger danger fears with people and dogs he doesn’t know. Going to the cemetery instead of a dog park (which is too scary for him) allows him to roam and check out his surroundings without fear.”

The cemetery staff makes sure to regularly refill water bowls scattered around, and dogs are given free reign to run off-leash within the fenced-in grounds. “The no-leash privilege combined with lots of areas to roam gives both my dog and me some exercise and the ability to get outside of our busy neighborhood on H Street,” says Hallberg. Owners are expected to clean up after their dogs, and the cemetery provides waste removal bags.

“Congressional Cemetery is, first and foremost, a functioning cemetery,” says Williams. “It’s actively interring members and hosting burials and ceremonies. It’s a beautiful space and a feature of the neighborhood, and our membership helps protect, preserve, and maintain the grounds.”

For those not keen on sharing their plots with pups, the cemetery is closed to dogs between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. every Saturday and on Easter, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Veterans Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. “Occasionally, there are critics who disagree with letting dogs use a cemetery, but they are often swayed when they see the immense contribution the dog walkers make to the cemetery,” says Maloy.

Presidents and public vaults

In 1807, the first burial at Congressional Cemetery was that of William Swinton, a stonecutter who worked on the Capitol building. Three months later, the cemetery interred its first Senator, Connecticut’s Uriah Tracey. Because of its proximity to Capitol Hill, almost every Congressman (the first woman wasn’t elected to Congress until 1916) who died over the next 30 years was buried alongside Tracey. Their graves are marked by unique stones designed by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Despite its official-sounding name, Congressional Cemetery—originally known as the Washington Parish Burial Ground—was established by private citizens. Now run as a non-profit organization, you don’t have to be a member of Congress to be buried here—“you just have to be dead,” according to the cemetery website.

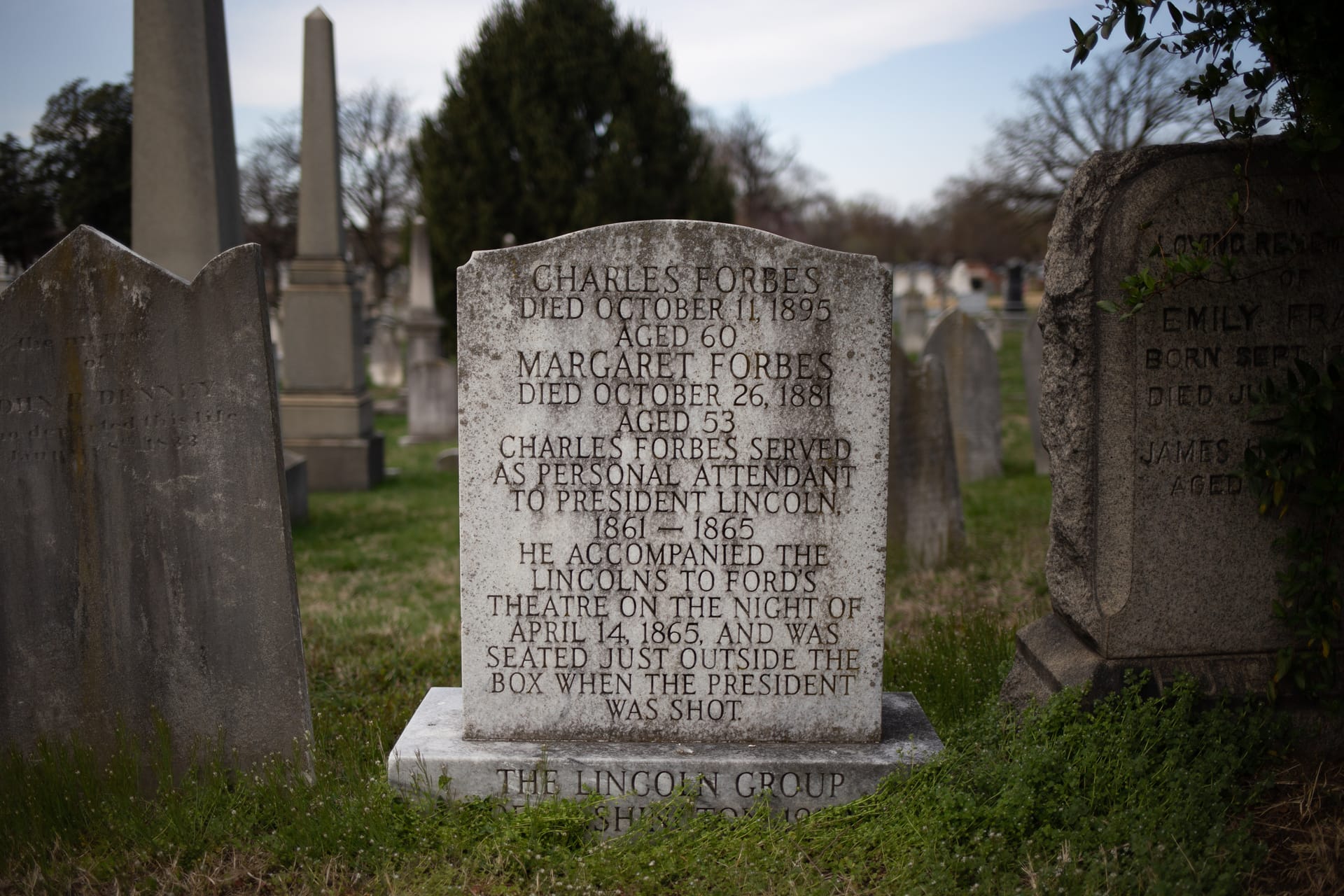

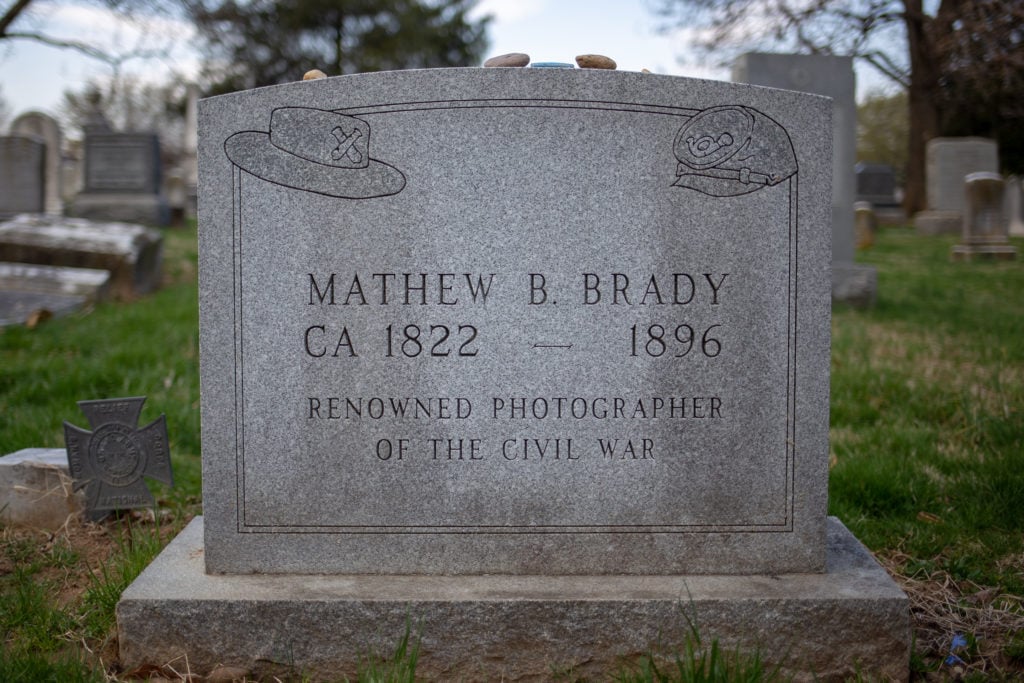

More than 65,000 people who fit that requirement are buried here beneath 25,000 headstones, including the first director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover; Push-ma-ta-ha, a Choctaw Indian chief, warrior and diplomat; Anne Royall, the nation’s first newspaperwoman; John Philip Sousa, the composer known as ”The March King”; Elbridge Gerry, the only signer of the Declaration of Independence interred in D.C.; and the father of photojournalism, Mathew Brady.

The very first burial at Congressional Cemetery was William Swinton, a stone-cutter who worked on the Capitol. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan John Philip Sousa was the leader of the U.S. Marine band. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The first member of Congress to be buried in Congressional Cemetery was Uriah Tracy. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Mathew Brady’s original headstone, which got his death year wrong. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Brady’s new stone was erected near his old one by fans of the photographer. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The cemetery’s public vault was built by Congress in 1835 and used as the temporary resting place of at least 6,000 people. The vault held the bodies of Presidents John Quincy Adams, William Henry Harrison, and Zachary Taylor until they could be buried elsewhere. First Lady Dolley Madison—who personally knew all of the first twelve presidents—remained in the vault for two years because her family couldn’t afford to give her a proper burial. The vault was restored in 2005 and is currently available to rent for events.

Gay corner

There are many factors that make Congressional Cemetery unique, but the one that has had the most lasting effect on me is its section of more than 30 LGBTQ veterans and activists. This “gay corner” may be the only one of its kind in the world—and the fact that Hoover and his protégé, Clyde Tolson, are buried nearby is not a coincidence.

When Leonard Matlovich, a Vietnam veteran, died in 1988, he specifically chose to be buried close to the former FBI Director and Tolson, his rumored lover. His black granite stone—reminiscent of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—is engraved with the words “A gay veteran,” and his last name only appears at the foot of the grave.

“Matlovich’s choice to be buried at the cemetery inspired other LGBTQ activists to be buried at the cemetery, including Barbara Gittings,” says Maloy. In the 1960s, Gittings, a prominent activist, closely worked with Frank Kameny, another significant figure in the gay rights movement who was fired from his job as an Army astronomer just for being gay.

Frank Kameny’s footstone. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan First director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover is buried here. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A bold statement bench in a cemetery full of dogs. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Tom “Gator” Swann’s death date hasn’t been added yet because he’s still alive. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Kameny appealed his dismissal by filing the first known civil rights claim based on sexual orientation discrimination, and Gittings joined him on the picket lines (he lost). Gittings and Kameny are now neighbors in the gay corner, continuing their activism even in death. Kameny’s footstone reads simply, “Gay is good.”

Some plots in the gay corner don’t yet have death dates inscribed because their owners are still alive. Tom “Gator” Swann, a “proud gay veteran,” has erected a stone with an alligator in a top hat and the epitaph, “Never give up hope or give in to discrimination.”

Proudly engraving your truth on a headstone is brave enough, but Herbert Kubli and Mark McElreath went one step further by marking their plot in the gay corner with a bench engraved with a photo of their two cats and the words “Cat lovers”—a bold move in the middle of a cemetery crawling with dogs.

But it’s Matlovich’s epitaph, which sits below two pink granite triangles, that packs the biggest emotional punch: “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men, and a discharge for loving one.”

A future for your four-legged friends

Planning for the future may seem like a tricky prospect for a space so rooted in the past, but Congressional Cemetery’s approach seems to be working. The cemetery’s first attempt at hosting goat yoga—the first event of its kind in the D.C. area—was a huge success. Grounds maintenance and upkeep aren’t cheap—people keep moving into the cemetery, but no one ever moves out—and finding new sources of revenue is vital to the cemetery’s survival. Congressional offers seasonal ghost tours, and visitors can pick up a brochure or download the cemetery’s app to find the graves of specific people.

“We have numerous other events at the cemetery, from 5Ks and historic walking tours to concerts and a Day of the Dog festival in the spring,” says Maloy. “We try to reach a diverse demographic through these events, and to ensure that the cemetery stays relevant to the community for years to come.”

Soon, dogs like Dray and Oskar will have the chance to enjoy Congressional Cemetery for all of eternity. In a move that may seem obvious, the cemetery plans to open the grounds to pet burials sometime this year. The Kingdom of Animals section—available to all animals, not just dogs—will be D.C.’s first official pet burial space.

“Promoting Congressional Cemetery as a community space allows, and even encourages, the community to be a part of Congressional Cemetery’s future,” says Maloy. “Those who use the cemetery for its many purposes love and respect this historic space.”

Williams adds: “It’s a beautiful, friendly, happy, and fascinating place.”

If you go

Congressional Cemetery is open every day except Monday from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m.