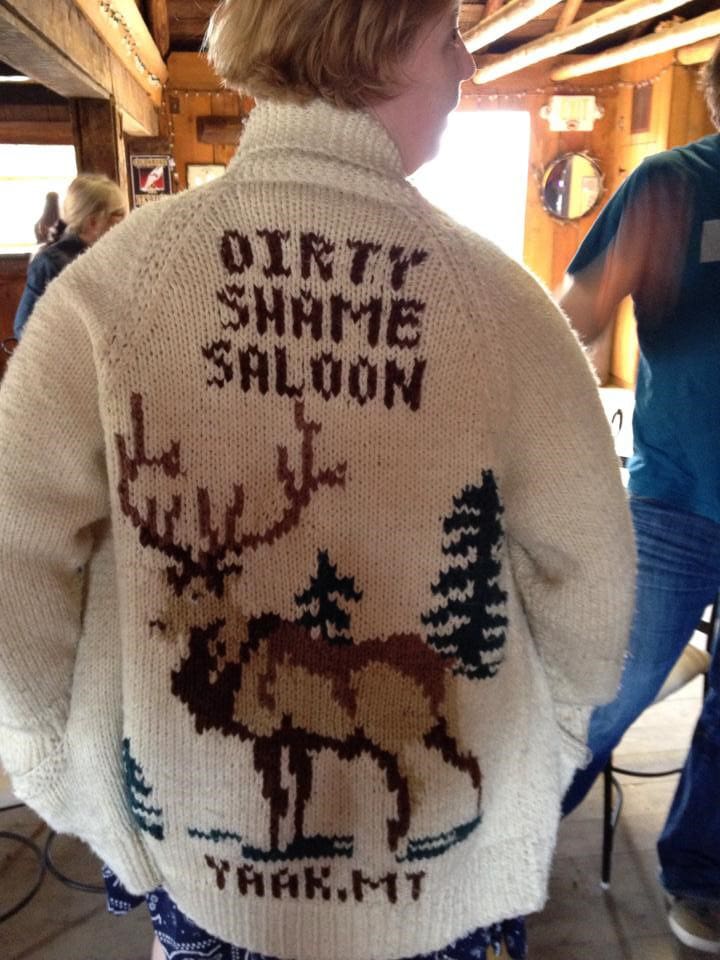

The Dirty Shame Saloon lives up to its name: Its interior is dark and wooden, with exposed beams and cattle skulls. Men in cowboy hats are eating chicken wings at a low table. Christmas lights made of shotgun shells hang above the bar while the television plays sports. A Jim Beam sign on a door is riddled with bullet holes. Hundreds of names are carved into the wooden walls, some of them by what must’ve been a chainsaw.

How did I, a vintage clothing picker from Seattle, end up in this mountain saloon in Yaak, a tiny hunting village hidden deep in the Montana forest?

It started with a sweater.

The 3 a.m. challenge

In the summer of 2014, my collecting obsession was Cowichan sweaters. Named for the Cowichan tribe, they’re winter-weight dad sweaters with chunky collars, like what The Dude wears in The Big Lebowski. I found an especially weird one on eBay and just had to have it. The only problem was that the auction ended at 3 a.m.

I’d never seen a Cowichan that advertised a business before, or even one with words on it, for that matter. The knitted pattern on the front spells out the name Willie. The back advertises the Dirty Shame Saloon in Yaak, Montana, alongside an elk and some pine trees. I needed to know: Who was Willie? What was the Dirty Shame Saloon?

My boyfriend Stephen and I had only been dating for a few months at that point, but my excitement about the sweater rubbed off on him right away. I couldn’t find anything online about the Dirty Shame Saloon, which made the whole thing all the more intriguing.

That’s when Stephen said, “If you win it, we have to go find this place, right?”

I set my alarm for 3 a.m. and ended up winning the eBay auction. The sweater arrived from Pennsylvania soon after: spotlessly clean, bright colors, not a loop out of place.

As for Stephen and me, we were going on a road trip.

Isolation station

The hunting village of Yaak—population 248—is way up in the northwestern corner of Montana, near the borders of Idaho and Canada, fully surrounded by the 2.2-million-acre Kootenai National Forest. The Yaak River Valley straddles the national border and acts as a sort of culvert for plants and wildlife from Canada, the Pacific Northwest, and the Rockies to flow together into a unique slumgullion of flora and fauna.

The unincorporated community was featured in the New York Times in 2017, touted as “The Last Best Empty Place in America.” Like many other very isolated communities in America, Yaak’s got a reputation in Montana for being a bit of a lawless place, where its residents take conflicts into their own hands rather than call the sheriff in from either Troy or Libby, both an hour away.

It takes seven and a half hours to drive to Yaak from Seattle, where we live, which is not nothing. It was a big step to take with someone I barely knew, but we really didn’t have a choice. We had to find out who Willie was.

Locating the lodge

The Friday we left for Montana, traffic was especially bad. But once we were through it, I-90 was wide open, hardly a soul between Wenatchee and Cheney, Washington. We sped quietly across Eastern Washington in four hours. From the road, I booked a room at Spokane’s Historic Davenport Hotel, a 1914 Mission Revival landmark that’s alleged to be haunted. The hotel is a palace in an otherwise scrubby business district, with an ornate marble lobby, a parquet ballroom, and gold leaf all over the fireplace. The dark, carved wood décor in the guest rooms evokes the Winchester Mystery House.

A summer street festival was happening outside on Sprague Avenue, and after check-in, we went out there sniffing around the vendor trucks. I paraded around in my cool sweater like I was Liberace, even though it was not cold, and bought some Vans from a woman selling clothes out of an Airstream. She told me that she and her husband had honeymooned in Yaak.

“It’s beautiful, but there’s nothing there,” she said. “There’s the Dirty Shame and another bar and a little store, and that’s it. Oh, and the hunting lodge. You’ll have to sleep there.”

In the morning, we ate at a diner shaped like a giant milk bottle—Spokane has two—before heading east. Spokane is on the eastern edge of Washington State, and things get rural fast once you cross the border into Idaho.

As we expected, what little services were offered in the Idaho panhandle disappeared as soon as we entered Montana. The Kootenai National Forest begins right at the border and you’re swallowed up by green mountains on all sides. There are few buildings. Hand-painted signs threatened us from time to time: Last place to get food for 50 miles! Last chance to gas up here!

The greenery got even more intense once we turned onto MT 508, aka Old Yaak River Road. Here, the signs started to be about bears instead of gas. A sign on a shack informed us that we could buy rabbits there. Last chance to stock up on rabbits. We discussed why this could be important. Maybe we should do it. (We didn’t.)

Where’s Willie?

We headed straight for the hunting lodge that the woman in Spokane had mentioned, which turned out to be called the Yaak River Lodge. Housed in an unremarkable, single-story structure, it reminded us of a government utility building. I had pictured something more like a Swiss chalet.

Not entirely unexpectedly, the interior relied heavily on dead animals. Bear skins covered the walls and stuffed bobcats and cougars struck curious poses on display shelves. All of the furniture was made of logs, including a small bar, which was flanked by three women in skinny jeans and ponytails. A stocked gun cabinet was the centerpiece of the room, and a rifle with a silencer was sitting on a table.

The ladies at the bar informed us that we’d arrived just in time for happy hour. Before we had a chance to order, the lodge hostess audibly gasped: “Oh my god, where did you get Willie’s sweater?”

“Oh my god, where did you get Willie’s sweater?”

While the other women gathered around me, I scrambled to explain what we were doing there, more than 400 miles from home, at a hunting lodge in the middle of nowhere.

“You have to go over to the Shame right now so John can see this,” our hostess insisted. “He will freak out.”

“So—you know Willie?” I asked nervously.

“Yeah, Willie used to own the Shame,” she responded. “And then this other guy owned it, and John, who owns this place, just bought it this summer.”

With that, a huge piece of our puzzle fell into place. Willie owned the Dirty Shame Saloon! I was happy to know this. My sweater felt like one of prestige.

Since arriving in Yaak, we were off to a pretty good start. Everyone was terribly friendly so far, and the very first person we’d met knew Willie. What were the odds?

It was time to finally visit the lauded Dirty Shame Saloon. And, with a little bit of luck, maybe we’d even run into Willie.

A dirty shame

We rolled the last few miles down MT-508 to the commercial center of Yaak—yet another town where the highway is also the main street. There it was, one of the town’s three buildings, an absolute spectacle in the middle of nowhere: the Dirty Shame Saloon.

After introducing ourselves to John Runkle, the owner, Stephen said, “We didn’t know if Willie was going to be here and want his sweater back.”

“Oh, no,” John said, his face suddenly serious. “Willie passed a few years ago. But she and her husband owned the Shame.”

Then John and the folks sitting at the bar proceeded to tell us all about Willie, who was nothing like the burly mountain man we had sheepishly pictured. She was petite, redheaded, and famously nice. She cooked the food at the saloon while her husband Rick tended bar. The t-shirts and hats sold at the saloon apparently once used to say “Rick & Willie’s” above the saloon logo.

Rick and his friends also liked to shoot the place up, for sport. “When I bought this place, we had to pull dozens of .357 slugs out of the walls and the floors,” John said.

She was nicknamed “Deep-Voice Willie” and for years, there was a painting of her behind the bar, wearing a big hat. Willie and Rick both liked to drink, we were told. John shared some semi-sordid tales about the couple, including one about how sometimes, when they got into a fight, Rick would go home and Willie would sleep on the pool table, to be discovered by the hunters who showed up in the morning for breakfast.

The bar began to fill up around then, and we were the stars of the Dirty Shame Saloon for the evening. I posed for dozens of photos and let various women try on the sweater. We met grouse hunters and Hells Angels and working cowboys, all of whom were as friendly as pie. We got countless rounds of free drinks from strangers and I told the story of the sweater over and over. No one could understand how it got to Seattle.

We also got the backstory of the bar: It was established in 1951 for the flyboys at the now-gone Air Force station in Yaak, originally just a metal hut outside the main gate. The extant roadhouse dates from the early ‘60s, after a log building replacement for the metal hut burned down. A bunch of smaller structures were reportedly just “jammed together” to form the current building.

And about that name. Allegedly, world champion boxer Joe Louis stopped by once and tried to order a scotch. When he was told they didn’t carry it, he replied, “Well, that’s a dirty shame.”

Homecoming

Although we never got a chance to meet her in person, Willie’s memory still looms large in the Yaak River Valley. We’ve been back to the Shame a few times since that first trip, usually in the summer to camp in the gorgeous, pristine wilderness. Every time we go, I bring the sweater, and we meet a new person who knew or was related to Willie and collect a few extra shaggy dog stories about her life.

Six years later, we still haven’t figured out how the sweater got to Pennsylvania.