The true Old West didn’t look like it does in Hollywood movies—it was much more colorful. An estimated quarter of cowboys were Black, and African Americans also shaped the region as farmers, pioneers, explorers, doctors, fur trappers, and hotel magnates.

A new driving tour app by History Colorado is dusting off a bit of this intriguing history. The Black History Trail winds through 150 years of Black heritage sites in the Centennial State, sharing stories along the way of pioneering people and events. While the tour can also be enjoyed from home, there’s arguably no better way to experience history than on a road trip.

Here are some highlights along Colorado’s Black History Trail.

Region 1: Southern and Southwestern Colorado

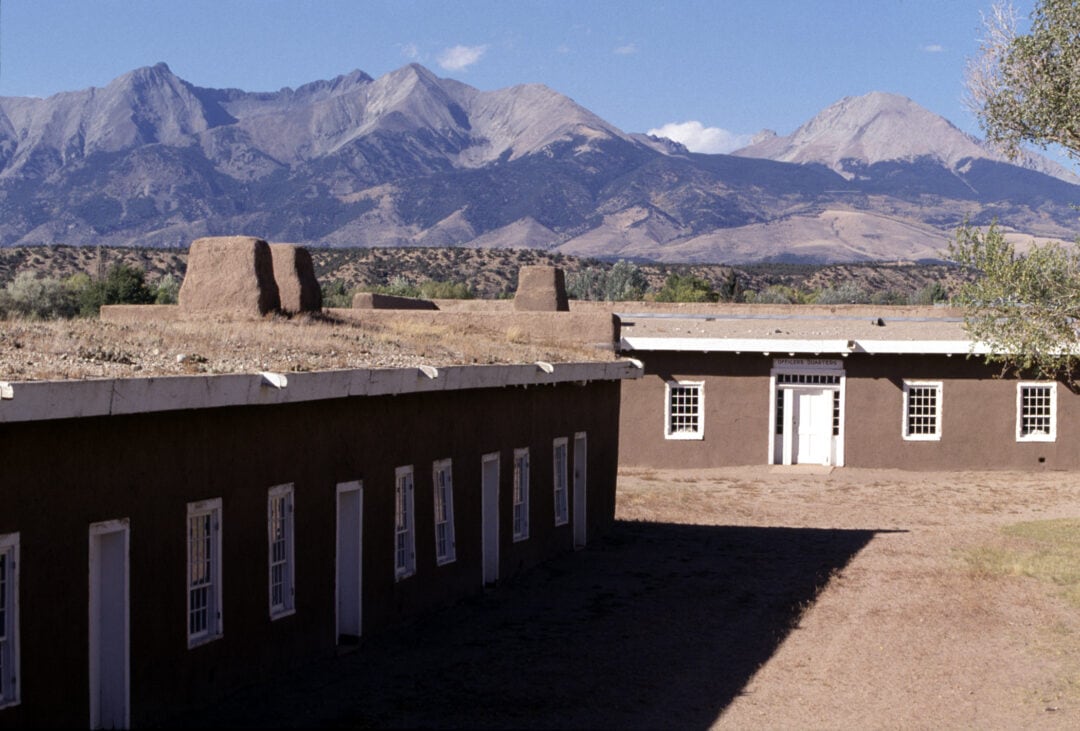

The men of the all-Black 9th Cavalry were stationed at Fort Garland, near today’s Great Sand Dunes National Park. They were known as Buffalo Soldiers, a term that may have been coined by Comanche and Cheyenne tribes, as a nod to their strong fighting abilities and curly hair. From about 1875 to 1879, the collection of Civil War veterans and formerly enslaved people were tasked with protecting settlers, travelers, and Ute tribes in Colorado’s massive San Luis Valley, once even having the unenviable task of evicting white settlers from Indigenous lands. It was a rough job, working at the confluence of three cultures. But the soldiers were stalwart as well as celebrated, receiving a remarkable 18 Medals of Honor.

The Fort Garland Museum is in the process of enhancing its exhibits on the Buffalo Soldiers, working with national artists to reimagine their legacy through mixed media installations that uncover “the intersectionality of Black and Indigenous history, innovation, frontier brutality, and an excavation of the soul.” Other stops in this region include sites tied to pioneer John Taylor, including the Pine River Valley and the Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum in Ignacio.

Region 2: Southeastern Colorado

After the Civil War, many Black people moved westward. The post-emancipation South was hostile, and the West beckoned with opportunity. Out on the plains, near Manzanola, two sisters took advantage of the nearly-free land offered by the expanded Homestead Act, and settled an area that would become known as The Dry, in 1916.

Other African Americans followed, and before long, there were around 20 families working the land there. By accounts, they were mostly embraced by the white community, borrowing tools from other homesteaders and being welcomed into the local cattlemen’s association. By the 1930s, though, a series of hardships—including the Dust Bowl and lack of adequate irrigation—prompted most of them to pack up for greener pastures.

Today, there are no standing structures left at The Dry, and it’s located on private property, but if you want to get a sense of the place, take County Road 11 just east of Manzanola. Another stop in this region is the El Pueblo History Museum in Pueblo, which tells the story of pioneer and mountain man James P. Beckwourth, who established early trading posts at Pueblo and in Reno, Nevada.

Region 3: Central and Northern Colorado

Up in the mountains west of Boulder, Black girls could spend their summers camping, riding horses, and learning archery at Camp Nizhoni (named for a Navajo word for beautiful). The camp was part of the Black neighborhood of Lincoln Hills, which was also home to Wink’s Lodge. From the 1920s through the ‘60s, the resort was a safe haven for travelers, including writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, and musicians Duke Ellington and Count Basie.

Lincoln Hills consists of all private residences, but Wink’s Lodge is being fixed up with the intention of eventually opening it to the public. To get a feel for the area, however, you can drive up County Road 17 in Gilpin County, and stop at South Boulder Creek, which also runs through Lincoln Hills.

Another stop in this region is the Barney Ford House Museum in the ski town of Breckenridge. Barney Ford was raised on a plantation in South Carolina, before escaping slavery and heading west in search of gold. He never did mine, but instead became a prominent businessman, starting with a barbershop and moving on to hotels, restaurants, and even part ownership of a mine. He was also a Black voting rights activist and the first African American to serve on a federal grand jury in Colorado. Beyond Breckenridge, there are other Ford landmarks around the state, including the Barney L. Ford Building in Denver (note that it’s not open to the public), and the State Capitol building, which has Ford’s likeness on a stained-glass window.

Region 4: Denver and Northeastern Colorado

Starting at the turn of the 20th century, Black culture, arts, and entertainment in Denver centered around a neighborhood called Five Points-Whittier. Racist real estate practices, such as redlining, originally forced the segregation of the area, but the ill intentions of those policies ended up creating a vibrant, upwardly-mobile Black community. It was sometimes called the “Harlem of the West,” as it had more Black-owned businesses than any other U.S. town except for New York City’s Harlem, and by 1920 it was one of the largest African-American communities west of the Mississippi.

By the 1950s, there were also more than 50 bars and musical venues here, drawing acts including Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, and Dizzy Gillespie. The neighborhood later suffered decline with increased crime and abandonment during the second half of the 20th century, but it’s now a designated cultural historical district on the upswing, thanks in part to economic investment projects.

The main road in Five Points is Welton Street, and the neighborhood runs from roughly the intersections of East 26th Avenue and Welton to 27th and Washington streets. The legendary historic music venue Rossonian Hotel and Lounge is being restored by NBA star Chauncey Billups. Other important stops include the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library (also the site of Denver’s annual Juneteenth celebration and one of just a handful of Black-operated research centers in the U.S.); the perpetually-awesome Black American West Museum, housed in the former home of Colorado’s first African American female doctor; and East High School, attended by actors Don Cheadle, Pam Grier, and Hattie McDaniel (McDaniel went on to be the first Black woman to win an Academy Award).

Further out on the plains is another Black homestead town. During the early 1900s, Dearfield was a thriving agricultural community of nearly 200 Black families. Today you can drive by the ghost town, which is located on Highway 34, 25 miles southeast of Greeley, or learn more about it at the Black American West Museum.

Editor’s note: In 2022, Karuna Eberl was an ambassador-consultant for History Colorado’s Black history audio tour.