Carla Brown’s biggest fear is death. In 2012, she was driving through Baltimore on her way to her office manager job at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). A bad storm had knocked down a stop sign, and a distracted driver hit Brown’s car. Luckily, the accident wasn’t as serious as it could have been, but in the split second before impact, Brown says she had a cinematic epiphany: “I really thought, ‘This is it,’ and I was most upset about all the things I hadn’t done. There’s just so much to see—and I want to see and do as much as possible.”

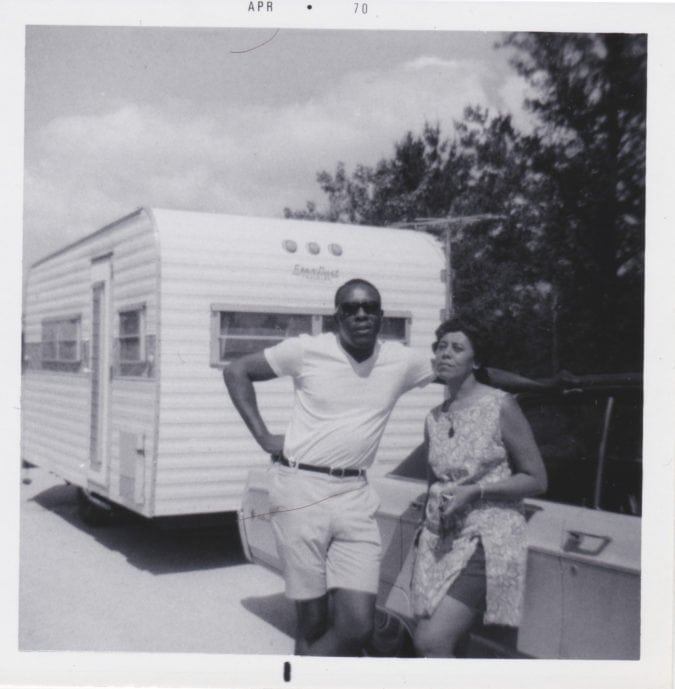

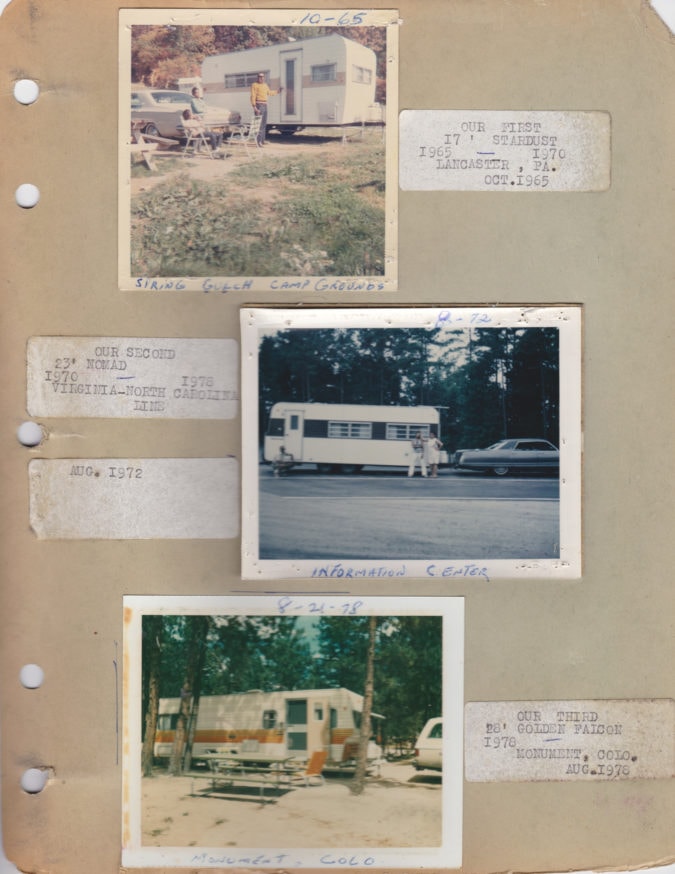

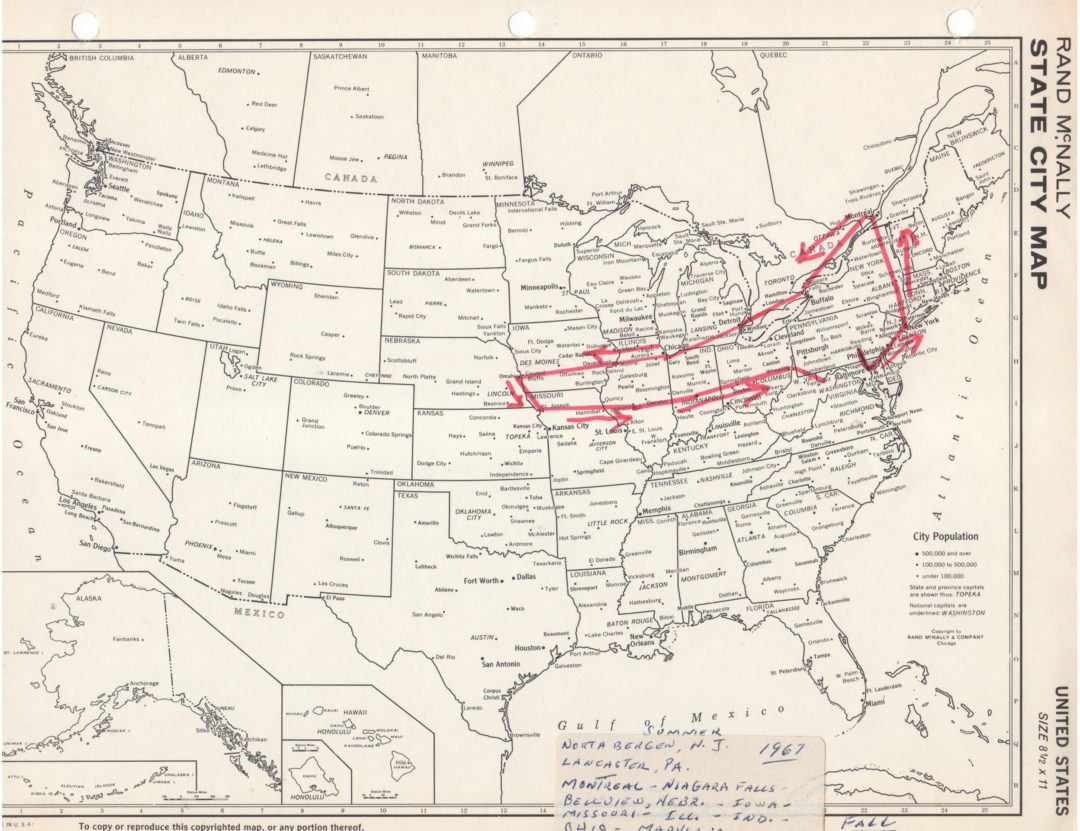

Brown knows that she’s not the only one who has grappled with her mortality or been struck by an insatiable case of wanderlust. There is no DNA test (yet) for the latter, but the travel gene runs deep in her family. In August 1965, Brown’s maternal grandparents, Benjamin and Frances Graham, purchased a 17-foot Stardust RV trailer and headed north from their Maryland home. Outlining their route with a red marker on a printed map of the U.S., the Grahams visited the New York World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, North Hampton Beach in New Hampshire, and Old Orchard Beach in Maine.

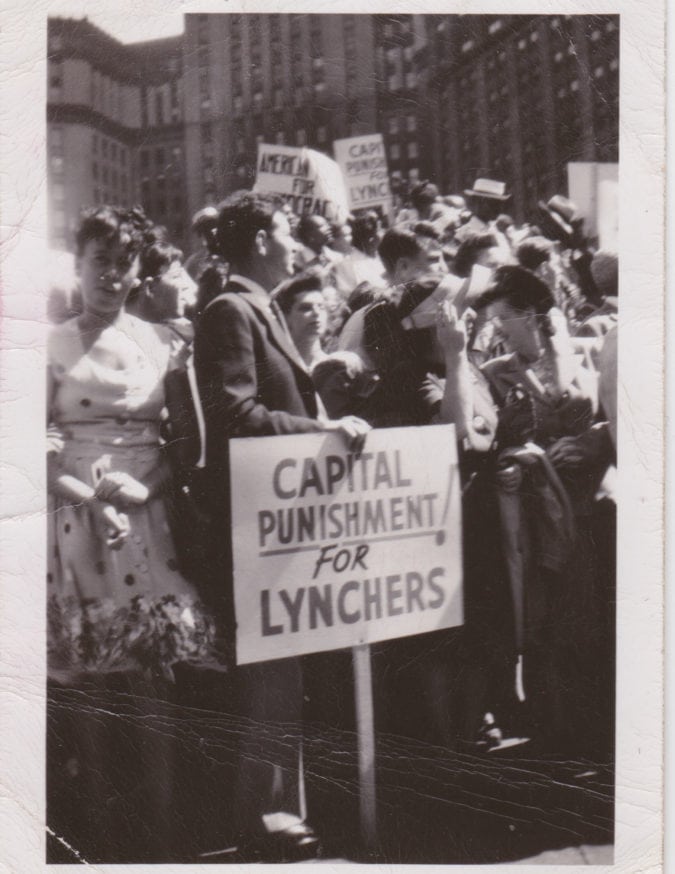

Just a few days before the Black couple embarked, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law. The day after the start of their East Coast road trip, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles erupted in unrest ignited by racially-motivated police violence. It was the latest spark at a time when the country was a powder keg, chock full of historic moments in the ongoing struggle for Civil Rights. But as far as she knows, Brown says her grandparents weren’t thinking about the symbolism of their chosen departure date.

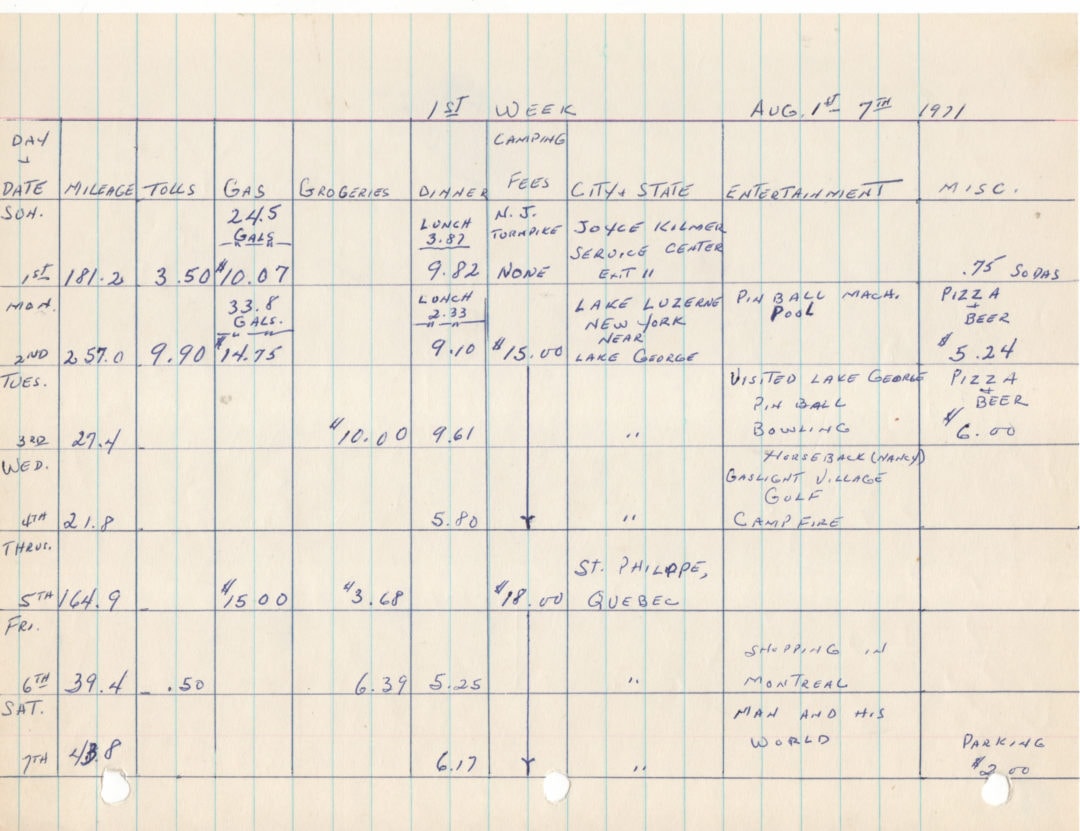

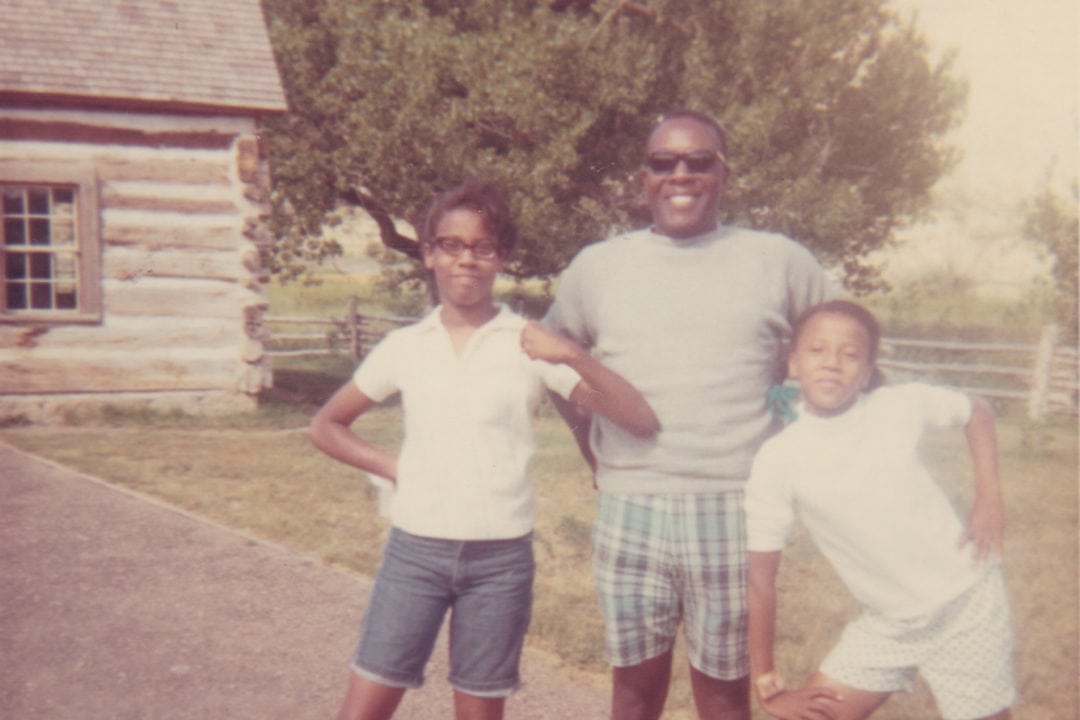

Benjamin was a WWII veteran and postal worker with a generous vacation policy; his wife was a teacher with summers off. They had three school-age daughters and just wanted to see the fair. The trip was such a success, they extended it—and then planned another. Over the next 35 years, the Grahams racked up more than 96,000 miles, taking dozens of road trips both big and small. For weeks or on weekends (with their kids, and then later alone) they criss-crossed the country, visiting every state but two: Alaska and Hawaii. Brown isn’t quite sure why her grandparents (Benjamin turned 95 this month and Frances died in 2016) kept such fastidious travelogues. But she’s glad they did.

In 2014, Brown embarked on a years-long journey of her own, retracing her grandparents’ steps and documenting it. She sifted through pages of handwritten notes, slides, and photographs; she watched hours of home movies and interviewed both of her grandparents and other family members. In mining her past, Brown was seeking to make sense of her own present; the required travel was a bonus. Almost 7 years later, the resulting documentary, Everyone But Two, is like Brown herself—still a work in progress.

“It might be a cliché, but it really is about the journey,” she says. “All of these amazing things I’ve seen and done on trips ‘in between’ what I thought was the beginning and end goal. But it’s everything in the middle that I’m going to remember. This has been a hell of a ride—and it’s not going to stop. I was born with the travel bug.”

‘A great American story’

I meet Brown for lunch at a French-themed restaurant in suburban Maryland. It’s her first day back in the office in more than a year, and she says I’ve caught her at “a weird time.” She’s always been an artist, but she didn’t set out to make a film. “Filmmaking is an evolution of the work I was already doing, and a film seemed like the best way to tell the story,” she says. “All I have to do is add my part of it.”

Her destination remains set, but the journey hasn’t been easy or simple. She lived in her parents’ basement for 5 years to save money, and talented friends have been generous with their time; but making a film isn’t cheap. She has applied for arts grants and sponsorships, her efforts yielding enough through the years to keep the project afloat. Everyone But Two is now at the point of post production—meaning that all the filming has been completed. All that’s left is to “take all the ingredients (editing, graphics, music) and bake a film cake,” Brown says.

Brown was in the process of securing finishing funds for the film when the pandemic hit; grant money dried up and she stayed close to home. Since her near-death experience, she says she’s had other epiphanies—and is fresh off another when we meet at the cafe. “Why am I back in an office?” Brown asks rhetorically. “I had a lot to think about on the road to work this morning. What are we doing? Really, what are we doing? All the people on the road going to the same place at the same time, it just doesn’t make sense.”

But it’s hard to take your own advice, and Brown says she’s always struggled with the conflicting needs for both consistency and change: “Everything’s throwing me back onto the road,” she says. “I’m having a lot of existential thoughts—clearly it’s something that’s in my blood. I’d almost always rather be on the road meeting new people, eating a new dish, or learning something I didn’t even know I could learn about.”

She understands that working remotely or “hashtag vanlife” is not for everyone. But Brown comes from a long line of people who didn’t mind living in tiny spaces—as long as they were mobile and headed somewhere exciting. “Domestically or internationally, I just want to travel,” Brown says. She even briefly considered signing up for a one-way ticket to Mars, but decided her tastes and talents were better suited for her home planet. “Plus, they don’t have pizza on Mars.”

She suggested this particular restaurant because it reminds her fondly of France. When I admit I’m a nervous flier who has seen very little of Europe, she suggests that a drive to EPCOT is almost as good as seeing the real thing. “This country belongs to everyone,” Brown insists. “There’s so much to experience, so much to learn in interacting with other people or in seeing how other people live. The world could use a little more empathy and we should enjoy what we have.”

She has a post-it note hanging up in her workspace to remind herself that she’s making this documentary “to tell the story, not to make money.” But Brown is also aware that more people who look like her are buying RVs and taking to the road than ever before. “Because I’m in this body, I think about it,” she says. “Yes, this is a great story for a woman of color—but it’s also just a great American story.”

Everyone But Two

Brown grew up in Baltimore, taking road trips with her parents and siblings in a station wagon. She racked up an impressive number of miles on her own, traveling to Aruba, Zanzibar, and dozens of states before she began replicating her grandparents’ itineraries for the film. The Grahams had plans to visit Alaska, but a surprise summer snowstorm kept them from crossing into Canada. Benjamin had wanted to drive the Alaska Highway, built in part by Black veterans he had served alongside in the war, but they never made it back. And you can’t exactly drive an RV to Hawaii.

Brown’s grandparents were friendly travelers, and she cherishes the time she’s had to get to know both of them as an adult—but they could be frustratingly vague when asked about their intentions. “They were just curious people and interested in seeing everything,” Brown says. “There was no rhyme or reason to what they saw.”

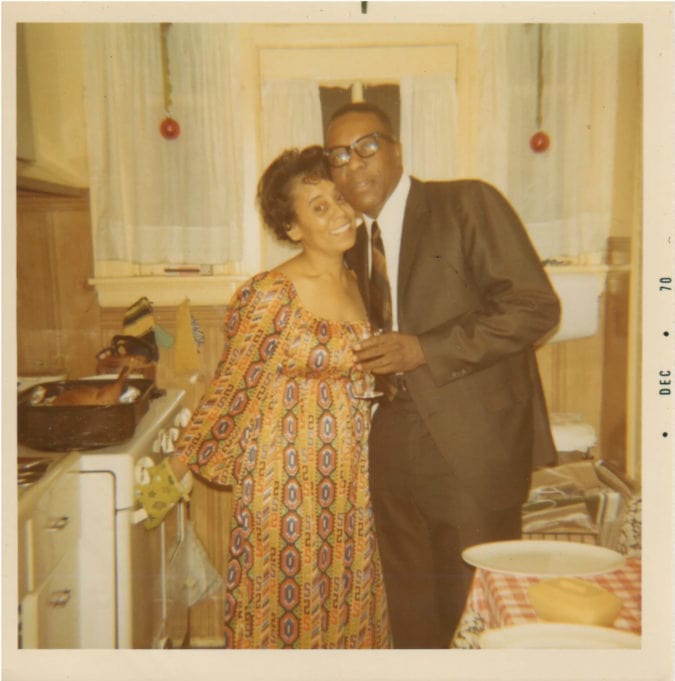

Family lore says that, although he wasn’t a big drinker himself, Benjamin would pour his wife a Highball every night they were traveling. While she drank her nightcap, the couple would pore over their paper maps and decide where to go next. If a fellow traveler suggested something interesting, they’d take a detour. And they weren’t just interested in seeing the U.S.—Benjamin’s first travel experiences came from being stationed overseas. The Grahams wanted to visit Asia and the Great Wall of China; they toured several European countries and loved the White Cliffs of Dover. When one of their daughters was stationed in Nebraska, trips were planned to include a stop at her Air Force base.

Brown says that a Polaroid showing her charismatic grandparents clinking glasses in front of a “Welcome to Arizona: The Grand Canyon State” sign (their 48th) proves that they were at least conscious of hitting certain milestones. Benjamin’s motto was: “Ain’t no point in living in this world if you’re not going to go anywhere.” But since his wife’s death in 2016, he says he’s done traveling. “It really was about the two of them,” Brown says, explaining the double meaning behind her film’s title. The Grahams were happy when their kids went off to military academies or got married, half-joking that their three daughters “ruined their trips.”

“Yes, they’d been to every state but two—but it’s as much of a love story to me as anything else,” Brown says. “They were [non-violent] Bonnie and Clyde in an RV. It was them against the world.”

Wanderlust at first sight

The Grahams both grew up in the same Baltimore neighborhood and attended the same school. But they met in New York City while on separate trips with mutual friends. “I asked my grandfather, ‘Was it love at first sight?’” Brown says. “And he said, ‘No.’”

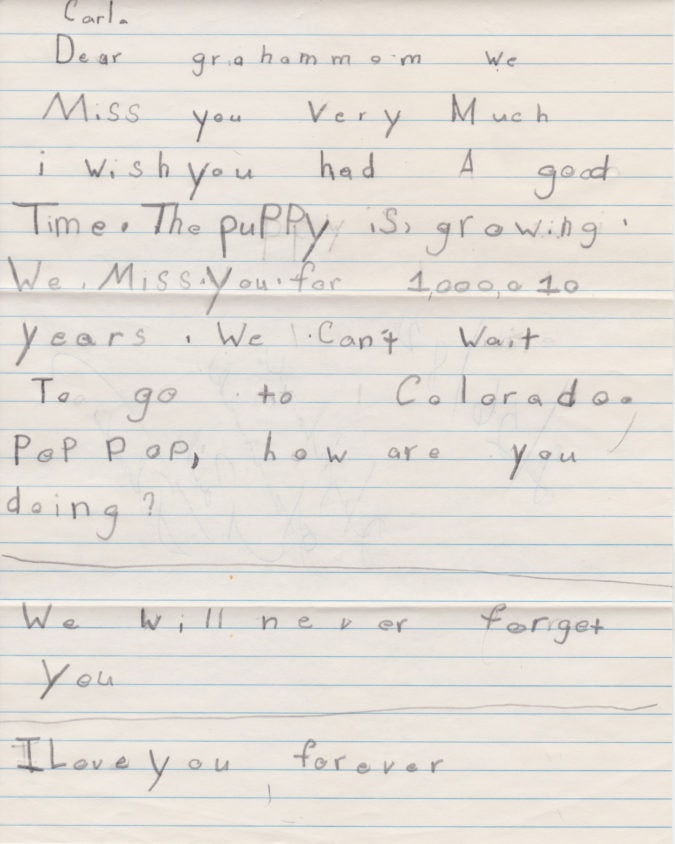

Brown was only 5 years old when her grandparents retired, and she never knew them when they weren’t traveling. Sometimes they would spend holidays with friends they had met on the road instead of their own family. Brown would send cards at Christmas or on birthdays, saying she missed them—but a love of travel was celebrated as a familial trait. “It just didn’t seem unusual,” Brown says.

When the Grahams both retired—before they embarked on their year-and-a-half long “big trip”—the family threw a party with a trailer-shaped cake. “I do think it’s genetic, the curiosity and willingness to take a risk, but whatever it is, it’s strong and grows stronger every day,” Brown says.

They weren’t big on souvenirs, but her grandparents collected t-shirts, and the basement wall of their home was lined with felt pennants from places they’d been. Sometimes Frances would spot a familiar location in a movie or TV show and call Brown just to say, “We’ve been there!”

The death of her grandmother was understandably difficult; Brown tears up when she describes the realization that Frances’ mobility was declining and her travel days were numbered. The last road trip they logged was to visit Brown in Wisconsin in 2003. After Frances died, Brown took herself on a solo trip to Aruba, swimming in the ocean and eating nothing but pizza. “My grandmother passed away, and travel was the remedy,” she says.

After losing his wife, and before the pandemic, Benjamin spent every morning at a local McDonald’s, telling tall tales with a group of buddies dubbed the Retired Old Men Eating Out (ROMEOs). The isolation of quarantine was difficult for him, and Brown claims that her grandfather “has never eaten a vegetable in his life” but intends to live until he’s 120. Described as a “character” who likes to bust chops and talk crap, Brown says she believes he’s telling the truth when he says he has no interest in dying—or traveling without the Bonnie to his Clyde. Five years after her death, Benjamin still refers to his wife of more than 70 years as his “girlfriend.”

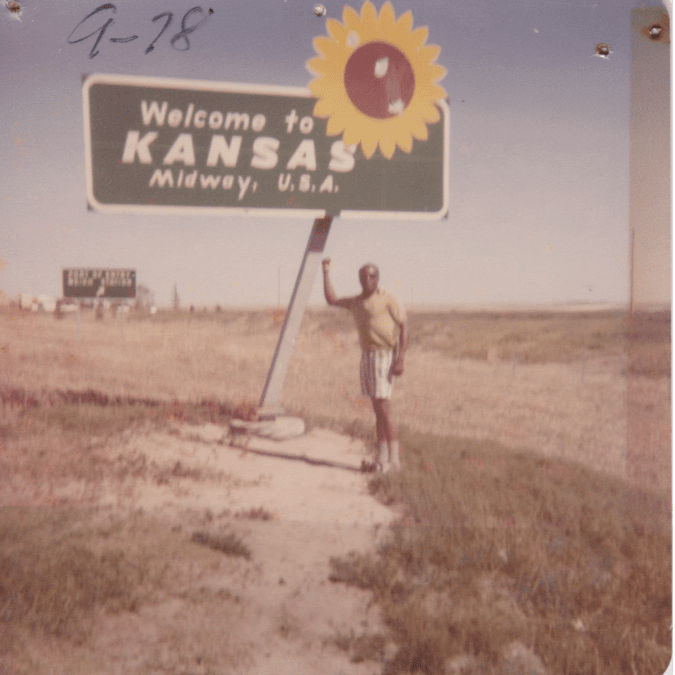

As a lifelong roadtripper, Brown understands that the road is often winding and full of unexpected detours. She has traveled to both non-contiguous states, completing her grandparent’s unspoken bucket list for them. But a hole remains smack dab in the middle of her own: So far, she’s visited every state but one. She’ll make it to Kansas eventually, but knows Benjamin probably won’t come with her. He’s been there already.

“[My grandparents] lived the great American Dream—to be on the road, to see the country,” Brown says. “Every place on the map is somebody’s home. But he’s not going anywhere without his girlfriend.”

The Grahams’ book

The Grahams didn’t believe in physical bucket lists, but they did make other lists. They were intentional about traveling all of the numbered routes across the country, and their binders include pages labeled “Places Worth Seeing Again” and “Roads Not to Take Again.” After three-plus decades, their albums were bursting with photos featuring “all sorts of people that don’t look like them,” Brown says. They received Christmas cards from all over the country.

There is no doubt that great strides have been made in making travel accessible (and welcoming) to all; and awareness of the racial disparities ingrained in every corner of the U.S. is once again at a Civil-Rights-era fever pitch. Progress is often painful. And pain sells. Brown says she has a love-hate relationship with her hometown, but she’s quick to point out that the social and economic issues that plague Baltimore are not unique. And not every day or neighborhood feels like an episode of The Wire.

“There are so many stories that haven’t been told and I’m so sick of Black tragedies,” Brown says. “There needs to be a much broader stroke of the African American experience in this country. I’m trying to change the narrative, but sometimes I wonder, ‘Is this story not depressing enough [to garner attention]?’”

‘Black people don’t camp’

Road trips may have always felt familiar to Brown, but many women, people of color, and other minority groups still don’t feel welcome in certain travel spaces. “Growing up, my friends would ask, ‘Why do you camp?’ or say, ‘Black people don’t camp,’” Brown says.

Today, as she drives through Baltimore, she says she thinks about the value of exposing oneself and others to a wide range of experiences. “There are a lot of people that look like me who don’t have the opportunity to see and do things—and a lot of it isn’t their fault,” Brown says. “For someone to want to get out of their neighborhood, get out of their state, or whatever that boundary is for them—if you can see it you can be it.”

Her grandparents may not have considered themselves activists or revolutionaries, but even small sparks start big fires. Brown knows that it was Frances who persuaded Benjamin to plan an annual trip coinciding with a segregated teachers’ conference. As a Black woman, she had no intention of attending; she staged a silent act of rebellion by taking to the road precisely when she did, making a statement with both her actions and deliberate inaction. And she always brought her husband along with her.

“If you met them you would think my grandfather ran the show—he’s so full of life, he’s a spitfire and has so much to say,” Brown says. “But it’s the opposite: It was my grandmother’s idea to get a trailer and to travel and he was just, like, ‘OK.’” They reported only two instances of blatant racism (both in Montana) and claimed they had never heard of the Green Book until recently.

“We are so much more alike than we are different,” Brown says. “That’s one of the treasures of traveling. My grandfather says he has no regrets and [traveling] was the best decision he ever made. But even when their answers are ambiguous, their actions speak louder than their words.”

UFOs and an Oprah moment

Brown originally wanted to study marine biology; she loves the water and “the mystery of all the things that live beneath it.” She’s also fascinated by outer space and UFOs. I bring up the idea of time loops to help explain, at least in part, why her grandparents kept such good notes. And why she was the one who rediscovered and connected with them when she did. Leaning into her weird moment, she agrees with me: “I would like to think there was some alien from the future that said, “Your granddaughter is going to need a project.’” Brown says.”The story was meant to be told, and I’m the one to tell it.”

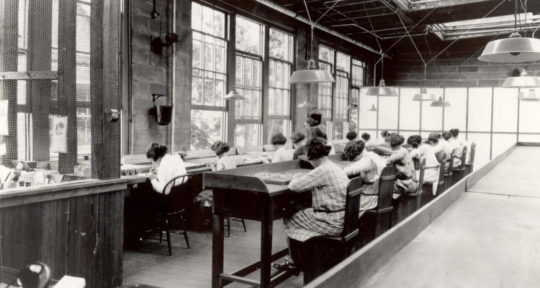

Inspired by a female teacher of color, Brown gravitated from science to art in an effort to explore the question of who gets to define what’s considered beautiful. She fell in love with printmaking, focusing on the intersection of cultural identity, race, and beauty. She got married and moved to Wisconsin. But she struggled with what it meant to be a practicing artist, and her marriage ended. Then her dad unwittingly helped fan the tiny campfire that smolders inside of every resting roadtripper by saying the magic word of the mid-2000s: Oprah.

Recognizing its value—if not its intended recipient—he gave Brown her grandfather’s meticulous travelogue and suggested she contact the immensely popular talk show host. “But it was also a self-discovery moment for me when I was already asking, ‘What am I going to do with my life?’” Brown says. “It was an epiphany; my own ‘Oprah’ moment. I thought, ‘Where can this go? And one thing led to another.”

In hand drawn maps and spreadsheets, Benjamin recorded how many miles they drove, and how much money they spent on gas, entertainment, and food (10 cents for a donut). Flipping through the decades of photos, fashion trends and film technology evolve. Kids become adults and the Grahams grow gray. Benjamin is almost always wearing shorts. It’s impossible to discern what they’re enjoying more while out on the road: looking at the sights, or at each other.

Brown has spent the last 7 years trying to recreate some of her grandparents’ original routes. She camps at state parks to save money, and travels by RV when she can. She has retraced their steps both to see what has and what hasn’t changed throughout the years. California’s giant Trees of Mystery may tower a bit higher over Brown today than they did when her grandparents visited, but the attraction remains mostly unchanged by time. She says she placed her hand on Paul Bunyan’s big blue ox and thought about everyone who found themselves in the exact spot before her—and all those trips yet to be planned, on purpose or otherwise.

Thousands of miles and memories later, Brown knows firsthand that “No trip ever goes exactly as planned.” She compares traveling to playing a pinball machine—every shot is different. “But nothing’s really changed,” Brown says. “We’re all trying to make something and have it stay. I just hope that something I did or said or shared will be enough to make someone else curious.”