Did you know that southwest Idaho is the birthplace of nuclear energy? Until a recent road trip, I didn’t.

Driving from Maine to Idaho, I sat in the backseat, admiring the vast, open spaces and silvery tumble weeds as we sped by. I admit I was a bit dismayed when we pulled off the highway at a sign for the world’s first nuclear power plant, now the EBR-I Atomic Museum. But I quickly realized I had nothing to worry about.

“People come in and are hesitant and think they will leave glowing or will see green, glowing, radioactive stuff,” says Ryan Weeks, a tour guide for Idaho National Laboratory (INL), which manages EBR-I. “When they see the museum—the science, the safety—they say, ‘I had no idea this was going on in Idaho. I had no idea this even existed!’ People come in with a lot of incorrect ideas, and they leave being wowed and amazed that this is how it all started.”

EBR-I, or Experimental Breeder Reactor No. 1, was built by the Illinois-based Argonne National Laboratory in the desert about 50 miles from Idaho Falls, Idaho. For the past 70 years, the 890-square-mile site has also been home to INL, the leading nuclear energy research laboratory in the U.S.

EBR-I was in operation from 1951 to 1963, and was the first power plant in the world to generate electricity from nuclear power. On August 26, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared EBR-I a National Historic Landmark.

Exhibits for everyone—autographs, no so much

Before entering the museum, through a 1950s-themed “living room” in the lobby, I am encouraged to watch an introductory video. The half-hour production features EBR-I workers sharing recollections from the early days of nuclear energy research. It leaves me in awe of the incredible bravery of these pioneers. The bootstrap engineering is both impressive and a little horrifying. In fact, toward the end of the video, participants discuss a small meltdown that occurred during an experiment. Fortunately, nobody was injured. The incident provided important safety information for the design of future nuclear reactors.

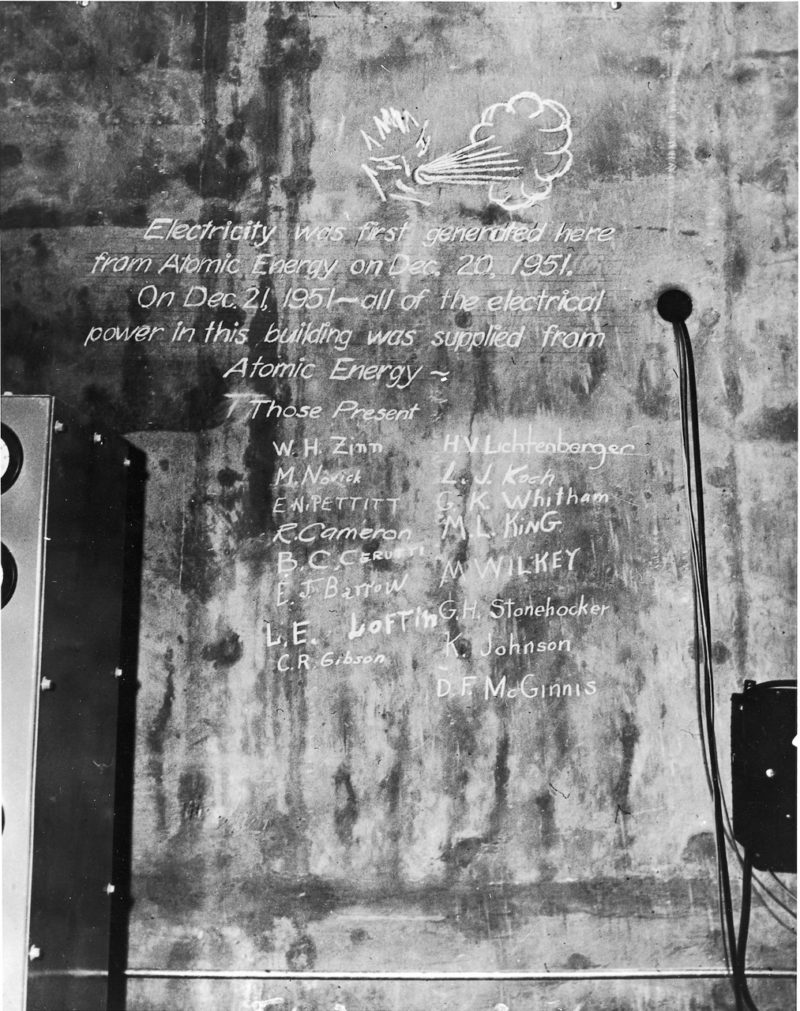

To commemorate the first successful generation of electricity from nuclear energy, physicist Walter Zinn and his team created a sign in chalk that reads: “Electricity was first generated here from Atomic Energy on Dec. 20, 1951. On Dec. 21, 1951, all of the electrical power in this building was supplied from Atomic Energy.”

It was signed by almost everyone present.

“One of the things not mentioned in the video is that on the wall, only the males were able to sign,” says Weeks. It was decided that project personnel should sign the chalkboard, but that support staff—the majority of whom were women—should not. And yet, the double standard is shown clearly at the bottom left of the sign, where the name of one lone support staff member is displayed—that of the male janitor.

It was not until National Women’s Month in 1994 that a plaque bearing the names of contributing women was added to the wall. At least one of those women, administrative assistant Wilma Mangum, made it into the video as well.

“There are still a couple of workers that signed the wall that come out to visit EBR-I,” Weeks says. “They are in their 90s and still kicking and sharp as ever.”

Ahead of their time

Brochures are available for self-guided tours, but having an enthusiastic and knowledgeable guide enriches the EBR-I experience. Weeks and colleague Misty Benjamin, a program manager in charge of community outreach for INL, are happy to answer questions about the history, safety, and exhibits, as well as about the future of nuclear energy.

“The magic of EBR-I is that we are standing on the shoulders of these technology giants and are able to inspire future generations who are going to create—I can’t even imagine at this point,” Benjamin said. “The folks that worked at EBR-I were definitely ahead of their time. It’s going to be great to see what the next generation, who had so much access to technology, will come up with.”

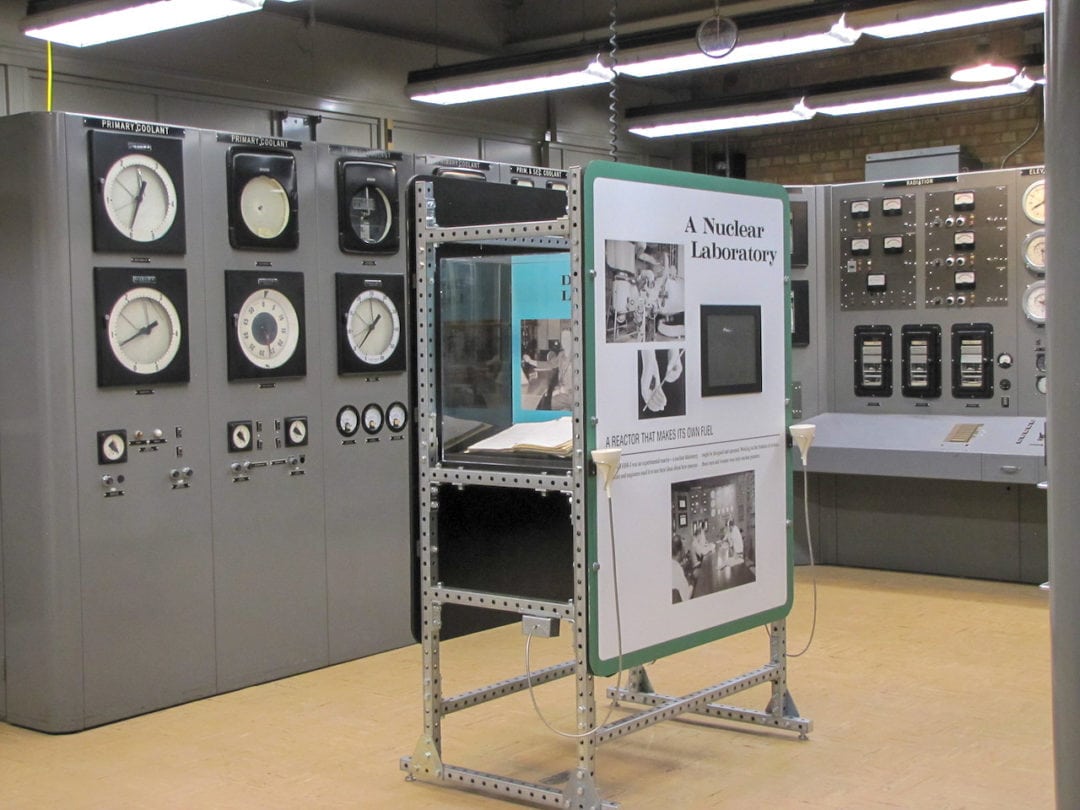

Part of the mission of the museum is to educate people about nuclear energy, and to attract the young people who represent its future. Since the museum’s inception, exhibits have evolved to include work done by INL since EBR-I shut down, a STEM education room featuring artwork derived from INL research, a station where visitors can build straw rockets, and other educational displays.

The museum is also filled with interactive exhibits. Manipulators allow guests to try their hand at moving blocks remotely the way scientists move radioactive materials. One such manipulator is a “glove box.”

“It’s basically a metal box with a window in it, and you put your hands in the gloves and move blocks around,” Weeks explains. “In the real world, this would be used for handling dangerous materials you don’t want to touch with your [bare] hands.”

The EBR-I Museum sees about 15,000 visitors each year. According to Benjamin, there’s a mix of international visitors, people on nationwide road trips, and retired nuclear industry workers who still feel a connection to it. For many, it’s a bucket-list item. EBR-I is also a popular destination for school field trips.

“Our STEM education display is meant to inspire young people that come to the museum,” Benjamin says. “That may intrigue them with a whole new field of science.”

Standing on top of a nuclear reactor is a unique experience, but, as Benjamin points out, it is the excitement and enthusiasm of the people who were engaged in the research—and the people still talking about it now—that makes it so powerful.

If you go

The EBR-I Museum, located 18 miles southeast of Arco, Idaho, is open to the public from Memorial Day weekend to Labor Day, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., seven days a week. Admission is free. Group tours may be scheduled year-round. Tour guides are available, but not necessarily on a schedule. Because the foot traffic flow fluctuates, guides try to begin tours when new visitors arrive.