It’s hard to travel anywhere along the East Coast and not run into Edgar Allan Poe. Although seemingly obsessed with death, the Master of the Macabre packed a lot of life into his forty years. He was inspired by every place he visited or lived in—for better or worse—and almost every major city from Massachusetts to Virginia has a home, museum, street, or park dedicated to Poe.

Boston, Poe’s birthplace, has an Edgar Allan Poe Square. The Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site resides in Philadelphia, along with the raven who inspired his most famous poem. New York City is home to the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, Edgar Allan Poe Street (W. 84th), and Fordham University, whose church bell is thought to have inspired Poe’s poem “The Bells.” Baltimore, the site of Poe’s mysterious death, has the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum, as well Poe’s grave (and several headstones).

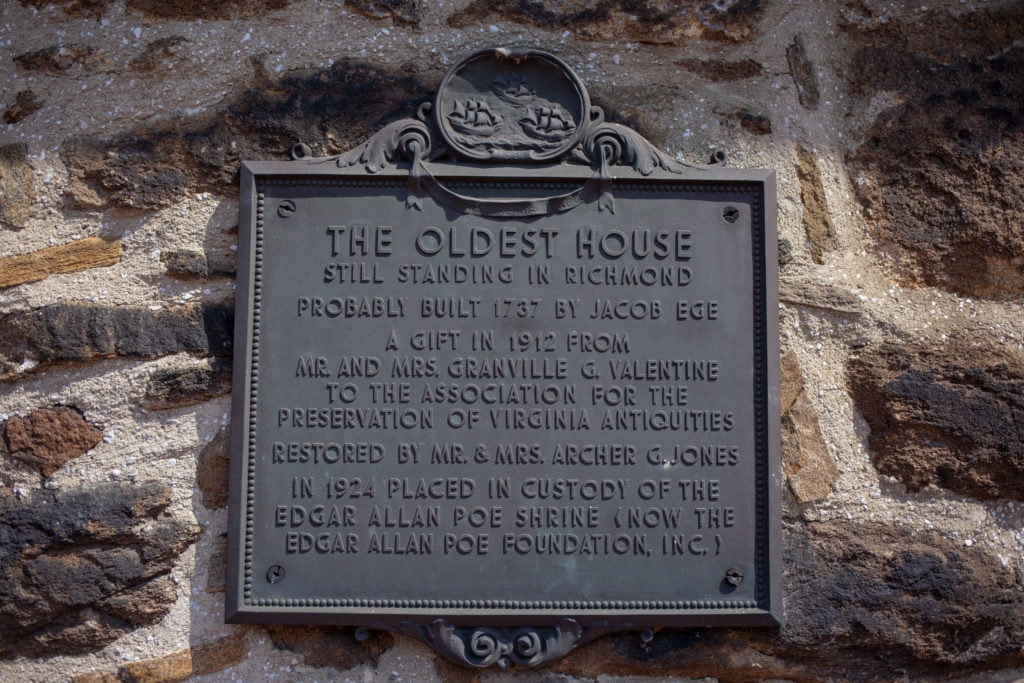

But even the Poe Baltimore foundation admits that it was in Richmond, Virginia that Poe most felt at home. Poe’s parents, David and Elizabeth Arnold Poe, were married in Richmond. After Elizabeth died of tuberculosis in 1811, the almost 3-year-old Poe was adopted by Virginia couple John and Frances Valentine Allan. None of Poe’s childhood homes still stand, but since 1922 the Old Stone House (c. 1730s) has been the centerpiece of The Poe Museum, Richmond’s love letter to its hometown hero of horror.

Poetraits and Poe-ka dots

The entrance (and exit) to The Poe Museum is through the gift shop, which displays and sells Poe memorabilia ranging from the macabre to the mystifying. There’s a portrait painted with real human blood, pouches sewn from “Poe-ka dot” fabric, enamel raven pins imprinted with the word “Nevermore,” candles scented like skeletal remains, and spices such as “The Masque of the Red Death Sriracha Sea Salt” and “Premature Burial BBQ Seasoning.”

The museum’s collection is spread over three buildings: the Old Stone House, the memorial building, and the north building. The latter two were built in the early 1900s. A sign on the entrance to a garden in the central courtyard, inspired by Poe’s poem “To One in Paradise,” lists 13 ground rules, or “Poe’s No-Nos,” including “Don’t feed any cats, ravens, or cannibals,” “Don’t dig up any graves,” and “Watch out for pits and pendulums. We don’t want you losing your head.”

Two black cats, who were born in the courtyard and never left, have free rein of the property. “Pluto is distinguishable by his white patch and he’s very friendly. Edgar is a bit more reserved,” according to the museum docent. If you think this sounds straight out of a Poe tale, you’d be right: “The Black Cat,” Poe’s short story about the dangers of alcoholism—and a vengeful cat named Pluto—was first published in the August 19, 1843, edition of The Saturday Evening Post.

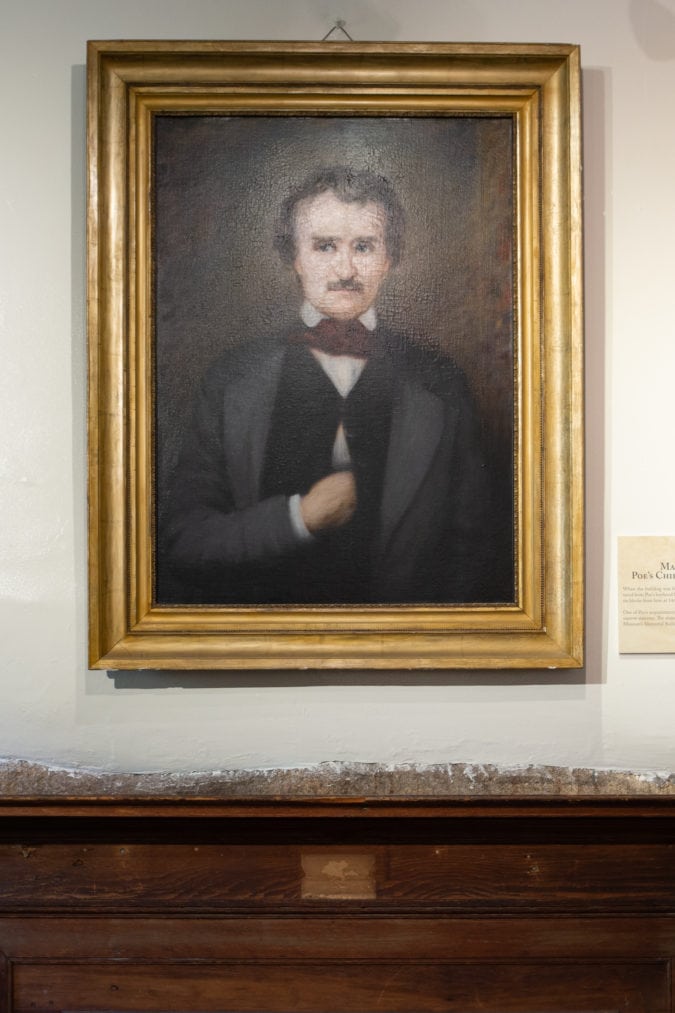

Poe never lived in the Old Stone House, but when he was 15, he escorted visiting French general Marquis de Lafayette to the house as part of his junior color guard duties. The interior now features furnishings from one of Poe’s childhood homes including paintings, a fireplace mantel, and Poe’s boyhood bed. The memorial building, built after another of Poe’s Richmond homes was demolished, incorporates the house’s staircase.

A life of misery and mystery

The museum is organized chronologically, beginning with Poe’s tumultuous childhood and ending with his tragic (and still unexplained) death. The largest museum collection of Poe memorabilia in the world contains genuine gems including several first editions of famous Poe tales, a Daguerreotype copy of what the museum describes as “both the most famous and perhaps the worst photograph of Poe,” and a fragment of Poe’s coffin. There are also some items of questionable historical value with a tenuous connection to Poe, such as his boot hooks, a soup ladle from his home, and his nail file.

-

The Ultima Thule Daguerreotype, which the museum refers to as “both the most famous and perhaps the worst photograph of Poe.” | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

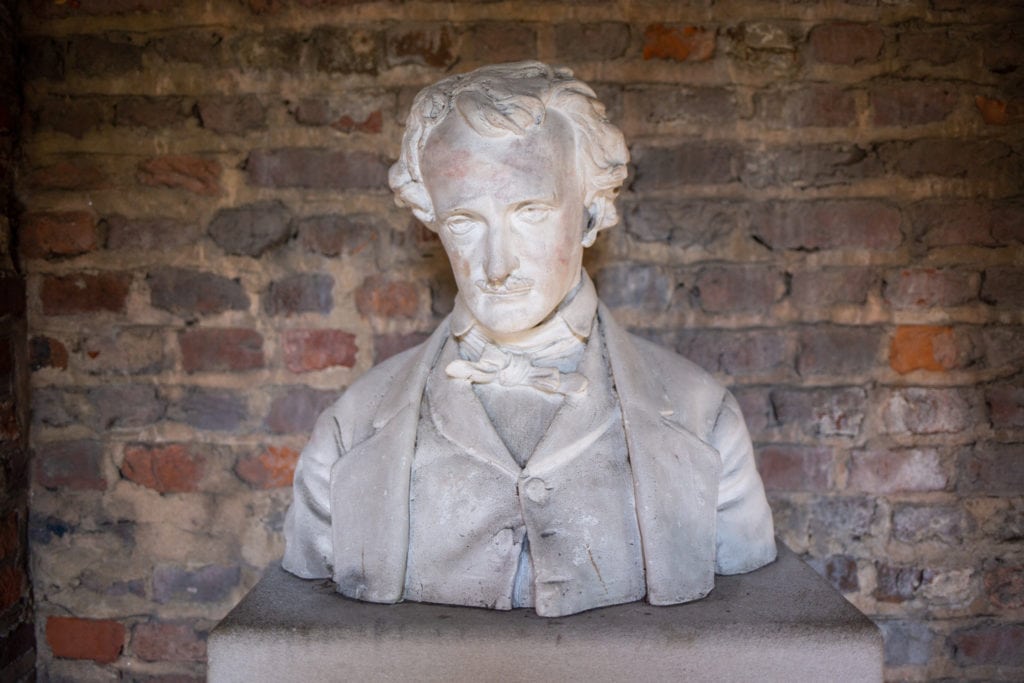

The museum includes several sculptures and paintings of Poe. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

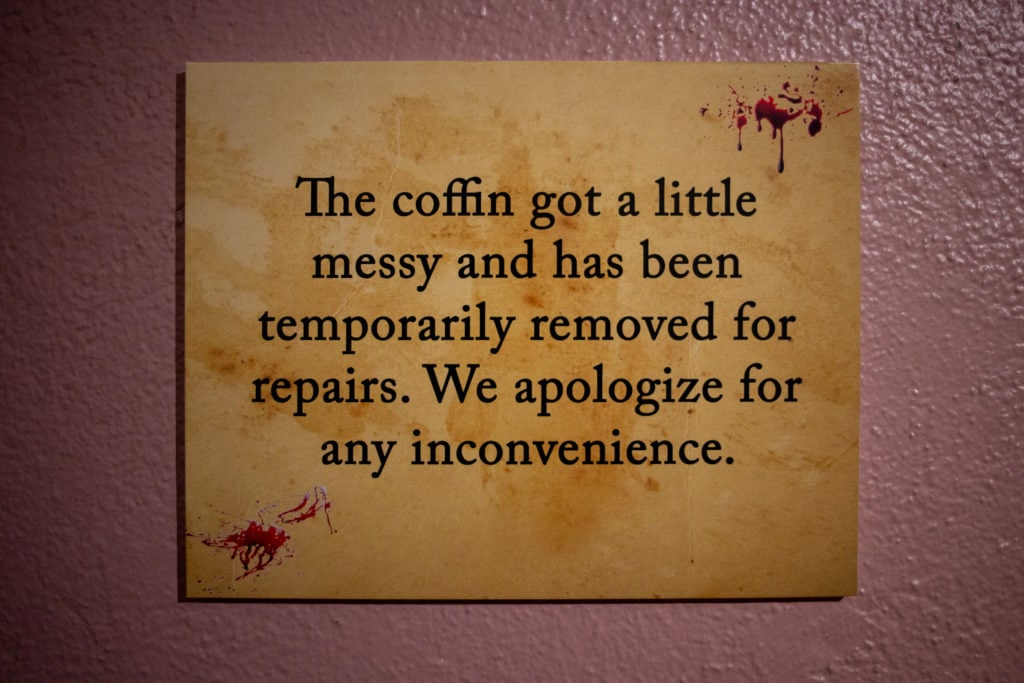

“The coffin got a little messy…” | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth presented this monument to the Metropolitan Museum of art in 1885. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Poe-traits. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

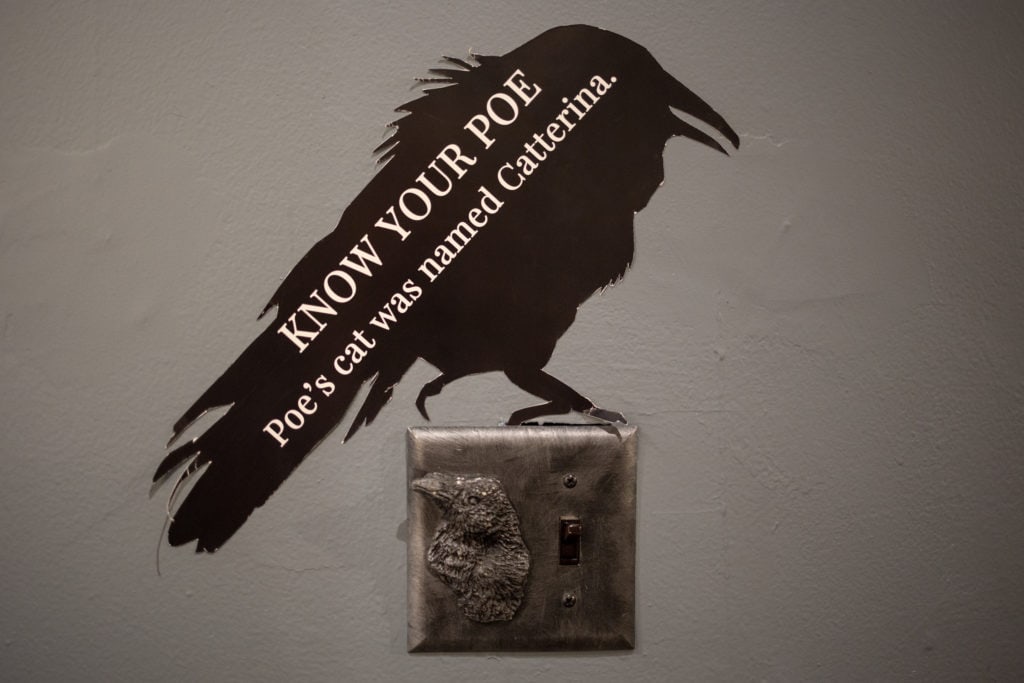

Poe, a fan of cats, wrote “The Black Cat” in 1843. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

But my favorite exhibit is actually the absence of one. In a corner devoted to Poe’s obsession with being buried alive, a plaque hangs on the wall above an empty space. Printed with blood splatters, it mysteriously states, “The coffin got a little messy and has been temporarily removed for repairs. We apologize for any inconvenience.”

The entire north building is dedicated to Poe’s equally mysterious death. On October 3, 1849, Poe was found on the streets of Baltimore, wearing someone else’s clothes. He was unable to explain how he had ended up in such dire straits. He died four days later and a definitive cause has never been found (everything from alcohol withdrawal to syphilis to rabies has been proposed). In 2002, scientists analyzed a sample of Poe’s hair, looking for a buildup of heavy metals. An exhibit titled “Poe’s Tell-Tale Hair” explains that although the sample did contain elevated levels of arsenic, lead, mercury, and nickel, none were high enough to add any clarity to his untimely death.

-

A copy of the bust given to the museum by the Bronx Historical Society. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The Enchanted Garden was inspired by Poe’s poem “To One in Paradise.” | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

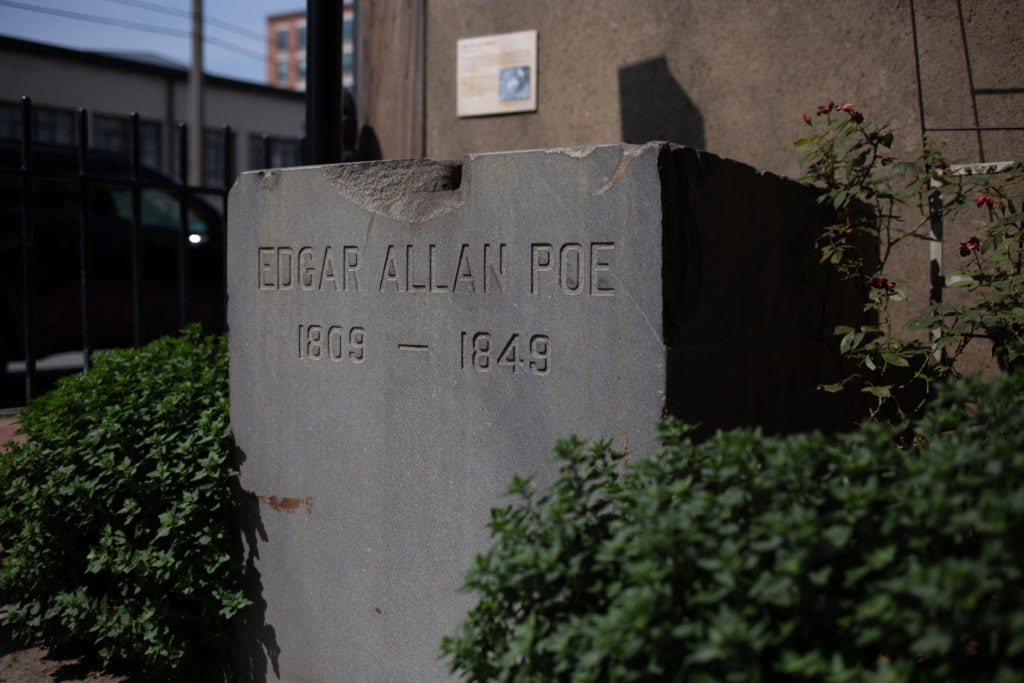

A recreation of Poe’s Baltimore gravesite. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

This half-ton basalt slab was found in a Richmond landfill. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

At the back of the Enchanted Garden is a shrine dedicated to Poe, featuring a copy of a bust donated to the Poe Museum by the Bronx Historical Society. After living in Baltimore for several years, Poe returned to Richmond in 1835, where he worked as an assistant editor at the Southern Literary Messenger. The shrine is built with bricks and granite that were salvaged when the offices of the Messenger were demolished in 1915. A sign posted nearby warns, “Don’t make Poe angry … please do not mark this bust.”

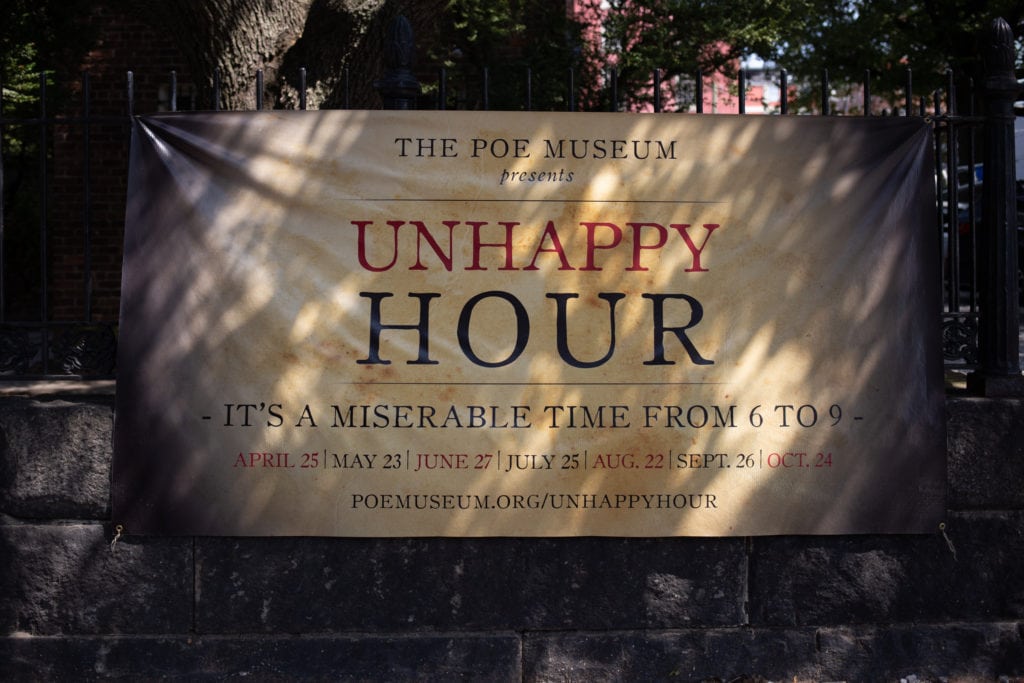

An unhappy hour

The museum regularly hosts readings, workshops, and talks. On October 24, the museum will host an “Unhappy Hour,” promising “Poe-themed fun for the whole family.” The event features a costume contest (with prizes for Most Beautiful, Most Horrifying, and Most Poe-Inspired), live music, and refreshments.

-

The museum regularly hosts events. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A sign for the museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The Old Stone House is the centerpiece of the museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

After the shrine opened in April, 1922, people from around the world flocked to pay their respects to Poe, including Gertrude Stein, Henry Miller, and Salvador Dalí. Today, the museum, located two-and-a-half hours south of Washington, D.C., attracts a diverse crowd. On a Wednesday afternoon in early September, there are about a dozen people making their way through the small museum, including a couple visiting from Turkey.

To me, catching a glimpse of the Poe Museum cats is just as thrilling as any celebrity sighting, and I eventually get my wish. Despite the docent’s warning, I’m pretty sure that Edgar is the one who approaches me, gratefully accepting my love and affection without any hint of reserve. Perhaps it is as Poe writes in “The Black Cat”: “Yet mad I am not … and very surely do I not dream.”

If you go

The Poe Museum is open Tuesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and closed on Monday.