After arriving on Ellis Island in the early 1900s, up to 6,000 immigrants a day would ascend to the Registry Room, located on the second floor of the main intake building. Doctors would assess the newcomers as they walked up the stairs, and if anything was amiss, a person would receive a chalk mark on their chest. Those with suspected mental defects were marked with an X. People with visible eye diseases were given an E, heart issues got an H, and pregnant women received a Pg.

If you were one of the two percent of people who received one of the dreaded chalk marks, you were either sent back to your country of origin—at the shipping company’s expense—or sent to the south side of the island, to what was once the nation’s largest public health service hospital. At its peak, the state-of-the-art hospital complex, built between 1910 and 1924, had thirty buildings.

While visitors to Ellis Island may be familiar with the fully-restored main building located on the north side of the island, the buildings on the south side—closed in 1954—are lesser known. They sat abandoned for 60 years before opening again for tours—in their unrestored, decaying state—in October, 2014. Save Ellis Island, a non-profit organization, began offering Hard Hat Tours in an effort to raise money to restore some of the buildings and to stabilize others in their current condition.

Island of hope

I first took the tour on a frigid day in January of 2015. Snow had drifted into some of the buildings through open windows and barren trees added to the eerie scene. The tour is a substantial 90 minutes long, but once was not enough for me and I returned this year on a much more hospitable day in June. I’ve explored my share of abandoned buildings (not usually on a sanctioned tour), and far from being depressing, I’m always struck by just how lively these otherwise-desolate places can feel.

Ellis Island in particular has stories in spades. Walking through long corridors and rooms darkened by the boards protecting what little window glass remains, it’s hard not to think about each and every foot that once made the floor creak as mine does. Abandoned places are unlikely record-keepers of our histories—not in the objects that they contain, but in the life that is notably absent. Chairs, rusty lockers, and desks are scattered about, forever stuck waiting for their human counterparts to return.

On the tour, visitors are allowed to enter select buildings, including the infectious and contagious disease wards, kitchen, laundry building, and mortuary and autopsy room. In a city where property is money, there aren’t many opportunities for visitors to legally explore buildings in such an exquisite state of decay.

John McInnes, director of operations for Save Ellis Island, says that the tour has been wildly popular. In the last five years, more than 100,000 people have donned a hard hat and braved the ferry crowded with tourists to get an intimate look at the crumbling structures.

“Preserving and restoring the hospital buildings is a complex, long-term project and Save Ellis Island is committed to increasing public access to the south side of Ellis Island during the restoration,” says McInnes.

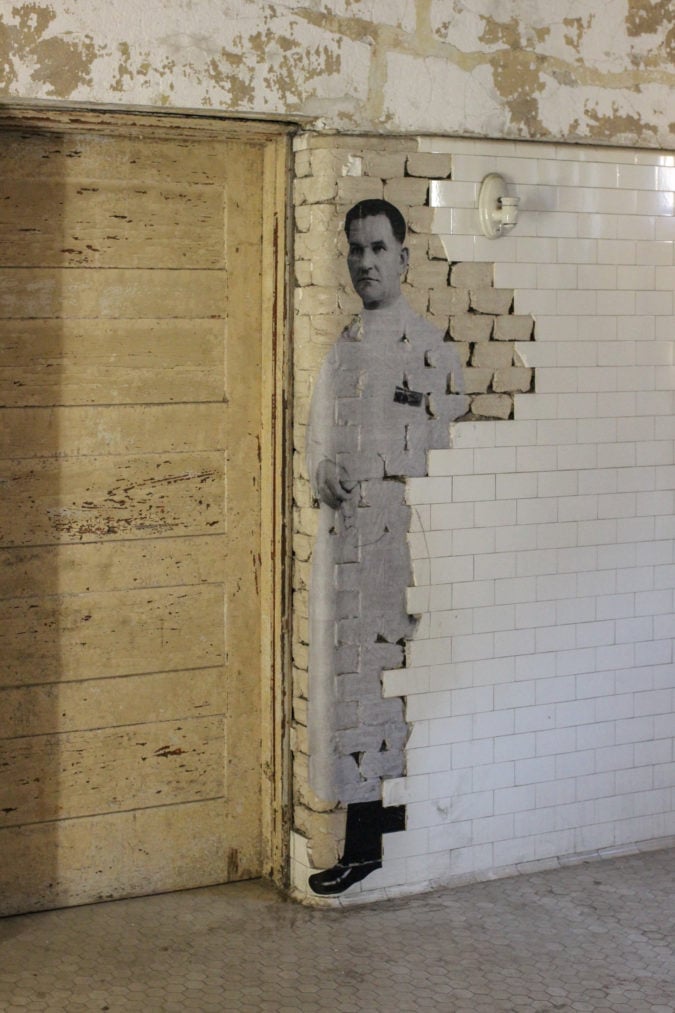

The buildings themselves are enough of a draw, but they also serve as a backdrop for an arresting art installation, Unframed—Ellis Island, by French artist JR. In 2014, JR approached the National Park Service, requesting permission to install large-scale photographs taken during the island’s heyday on the walls and facades of the unrestored hospital complex.

“Save Ellis Island immediately saw in his demonstration of what he intended, that his art made the buildings come alive,” says McInnes. “It was this partnership between art and history that became an integral part of the reopening of the hospital complex.”

With any luck, the buildings won’t be crumbling for long. Save Ellis Island receives no state or federal funds, so they rely on revenue from tours to fund their restoration mission. “Our long term goal is to fully restore many of the buildings for historic interpretation and reuse,” says McInnes. “Others will be kept in a state of arrested decay—a kind of suspended animation that prevents further damage while showing what happens to historic sites if they’re not actively managed and preserved.”

Island of tears

From 1892 until 1954, more than 12 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island. One in three Americans alive today can trace their heritage to someone who was processed on the 27-acre island in the New York harbor. The mostly man-made island continuously welcomed ships overflowing with steerage passengers eager for a new life in a new world (first- and second-class passengers were afforded the luxury of being processed on board their respective ships, and thus avoided Ellis Island altogether).

People were screened for health problems before they left for America, and once again when they arrived at Ellis Island. “The name of the game here is you had to arrive to be an able bodied citizen,” says Brett Moyer, a tour guide with Save Ellis Island.

Sending people back overseas was costly, and spreading diseases into the already-crowded streets of New York was a valid concern. In an attempt to encourage good hygiene, the Red Cross gave each person arriving at Ellis Island a bar of soap.

By the time the hospital was fully-operational, more than 10,000 patients from 75 different countries were treated in a year. But passing that initial health screening was not the end—and often just the beginning—of the trials faced by new Americans.

“Ellis Island is called ‘The Island of Hope, The Island of Tears,’” says Moyer. “But I think it’s a very hopeful island. I think the real island of tears is Manhattan.”

Death, disease, and over-crowding awaited anyone who chose New York as their final destination. Jobs were scarce, tenements were packed, and life expectancy was only in the mid-40s. On Ellis Island, however, the hospitals had a death rate of only about 1.6 percent. 3,500 people succumbed to diseases such as flu, tuberculosis, measles, or scarlet fever and were often buried on Hart Island, the city’s largest potter’s field.

At the general hospital for physical and psychological ailments, newcomers were questioned to determine their mental capacity or to see if they were a potential threat to society. When asked about the correct way to wash stairs—do you start at the top or the bottom?—Moyer says one woman famously replied, “Sir, I did not come to America to wash stairs.”

Despite the risk of infection, doctors and nurses lived on the island among their patients. A five-bed, four-bath doctors’ residence features fireplaces, ornate moldings, and sweeping harbor views. If given the choice between a Lower East Side tenement and a mansion in the middle of an infectious disease hospital, I would personally pick the latter. The fact that the doctors’ families were allowed to visit, but not live on, the island is a bonus.

“Caring doctors, nurses, and support staff treated hundreds of thousands of newcomers for conditions that would prevent them from working or endanger public health,” says McInnes.

So close, yet so far

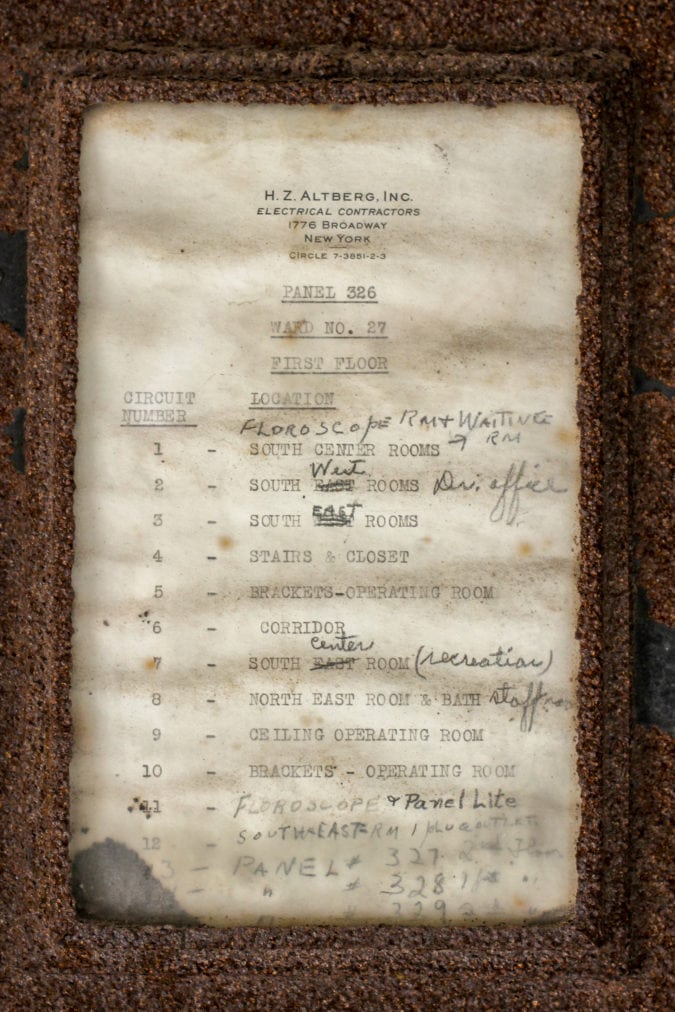

The hospital complex was ahead of its time in many ways. It was one of the first facilities in the country to employ a full-time female physician; wards were open, warm, and inviting places with large windows for optimal ventilation and light; and doctors implemented the latest technologies including x-rays and fluoroscopy. It was the first hospital to install a buzzer system (in 1911) and an autoclave capable of sterilizing an entire mattress can still be seen on the tour.

The hospital was so prestigious that “once you worked here you could go anywhere,” says Moyer.

The infectious disease hospital had 17 separate wards, connected by a central corridor. Each room in the tuberculosis ward features two sinks—the smaller, higher of the two was used by patients coughing up blood. The wood floor is covered in burlap and a thin layer of concrete so it can easily be sanitized.

Although the 10-to-1 patient-nurse ratio was considered excellent at the time, Moyer shows us an archival photo of one nurse, who looks less than thrilled to be surrounded by her infectious patients. “You cover ten patients with the flu and you’re not going to look happy,” he says.

In one room, a mirror reflects a view of the nearby Statue of Liberty, a coincidence that Moyer describes as “inspiring but cruel.” “Patients were so close to America, but so far,” he says.

Three times a day, 500 hot meals were made in a surprisingly small kitchen. A separate kitchen prepared meals for those adhering to a Kosher diet, but not everyone was impressed with their introduction to American cuisine. “A lot of farmers were offended when they were served oatmeal,” says Moyer. “Back home, it’s what they fed their animals.”

The south side of the island not only saw death, but life as well. 350 babies were born in the hospital and often named for a doctor or nurse. The island’s foreign, man-made soil made the child’s journey even more complicated.

“For the first time in 60 years, visitors can stand in some of the same rooms and corridors as the patients who received care in the Ellis Island Hospital,” says McInnes. “They can imagine the emotions of immigrants who, despite language barriers, understood the dedication of the doctors, nurses, and support staff who worked there. And in the walls, floors, ceilings, and windows, visitors can see the urgency of the need to preserve these structures and their story.”

Patients were retained only until they were deemed healthy enough to move on, and one-third of the people leaving Ellis Island had only a short journey until they arrived at their final destination: New York City. The other two-thirds traveled to New Jersey, where they caught ferries to other parts of the country in search of a new life.

“If the Ellis Island Hospital had not existed, many Americans would not be here today,” says McInnes. “It is a monument for when America extended care and compassion to travelers to our shore.”

If you go

The tour is approximately 90 minutes and 1.5 miles long. Tickets are available through Statue Cruises and may also be purchased on Ellis Island. Same-day ticket sales are available on a first-come first-served basis