Car culture is central to life in many American small towns: Rituals like weekend cruises and fixing up a first beater become rites of passage where distances are long, gas is cheap, and public transportation nonexistent.

But even among the most car-crazy of small towns, Española, New Mexico stands out. It has long been the definitive mecca for a breed of truly special cars. Thanks to their defiant individuality and sheer artistry, these cars have become central to an entire culture.

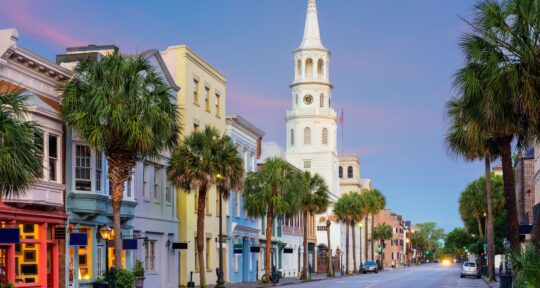

Known for generations as the “Lowrider Capital of the World” (and the only city in America with an “ñ” officially in its name), this historic crossroads straddling the Rio Grande had earned a reputation far and wide. “Growing up in east L.A. in the 1980s, Española was legendary. We thought every single person drove a lowrider,” says Raúl Ortíz, a practitioner who now lives in Albuquerque.

A 1970s Pontiac Grand Prix, one of the most popular body styles for lowriders, in the parade. | Photo: Tag Christof

“Q-vo,” short for “¿Que hubo?” or Spanish slang for “What’s up?.” | Photo: Tag Christof

A classic non-lowrider Buick in the parade. | Photo: Tag Christof

Lowriders and their builders were, in fact, integral to life in the town: California-based Lowrider magazine often printed photos of cars from the area and local high school yearbooks showed off the prized rides of students. Photographers like Miguel Gandert built careers beautifully documenting the life and style of the people behind the cars. Several area car clubs and workshops became nationally-known and, for a town of its size, Española was once home to more than its fair share of drive-ins.

As tastes and the local economy shifted over the years, lowrider culture in Española became less and less conspicuous—it even became possible to drive across town without seeing one of the lauded vehicles. For most of this decade, though, local members of the lowrider community have been organizing relentlessly to stem the tide. They are working to kickstart a renaissance for the rolling sculptures that made the town famous, and perhaps even boost local pride in the process.

“We have so much love for this valley and the community, and we really are working on building something big and positive to focus on, to leave for the kids,” says Joan Medina, who along with her husband is a giant among local organizers.

Their hard work has culminated in both a series of annual events that include a massive Lowrider Day parade, as well as a new lowrider museum that will be the first of its kind in the world.

Low and slow, por vida

Lowriders have had a storied place in Chicano culture that dates back to the era of pachucos and zoot suits. But while these one-of-a-kind rides were always far outnumbered by conventional cars in the large cities of Southern California—and even in Albuquerque and nearby Santa Fe—in Española, they had reached a critical mass by the 1970s. While it was never true that everyone in town drove a lowrider, they were in any case a more common sight here than anywhere else for decades.

Well into the 1990s, the town’s two main streets and many drive-in parking lots buzzed with bumper-to-bumper traffic on Friday and Saturday nights as locals cruised their immaculate, elaborate rides from end to end of town.

Lowriders were usually packed with groups of homies or families out for a cruise. Many sported the insignias of clubs representing nearby villages like Alcalde, San Pedro, Hernández, and especially Chimayó. There were rivalries, but cruising was generally a friendly affair, with drivers looking to show off their hard work and onlookers eager to check out the latest and greatest of these rolling works of art.

“When I was in high school there was an A&W stand on the main drag where we would go for root beer floats in iced mugs,” says Ruth Gutiérrez, a retired teacher who grew up in nearby Velarde. “We would often ride in the back of someone’s pickup truck through town, watching the lowriders cruise. We were never bothered by anyone. It was a peaceful, safe place to be.”

The cruise was a blend of pageantry, fashion, cultural pride, engineering skill, and artistry on full display every week—all in the context of a city that, on its surface, could have passed for any quaint, friendly American small town.

Beginning sometime in the 1980s, though, Española began to lose its cultural luster. As nearby Santa Fe, Los Alamos, and Taos grew wealthier and solidified their places as unique centers of art, science, and history, Española—lacking both a cohesive tourist narrative and a lucrative local industry of its own—was hollowing out.

The opening of a large Walmart in the late 1990s finished off many of its mom-and-pop shops and restaurants, and the town’s de-facto center is now a large tribal casino. For the majority of tourists who pass through, Española has become just another pitstop, a place to gas up between Santa Fe and the handful of picturesque attractions farther to the north.

Still, civic pride is strong in the area. Its culture, foodways, and linguistic traditions continue to set the valley apart, and locals have always been tenacious in their love of hometown. Various organizations have emerged in support of regional arts and culture, and the scrappy local newspaper, the Rio Grande Sun, has become an excellent case study in how to survive with integrity as a small town print rag in a digital age.

For many, though, the key to real revitalization involves recapturing the glory days of its unique culture: It might not be brainy Los Alamos, mystical Taos, or artsy Santa Fe, but Española is at its best when it is able to exude its own cool nonchalance, cruising forward low and slow.

Chimayó Michelangelo

One family, perhaps more than any other, has been a driving force behind the resurgence of lowrider culture in town. Joan and Arthur “Low Low” Medina founded the Española Lowrider Association, and along with extended family and close friends, were behind much of the hard work that led to the founding of the upcoming museum. Since 2017, they are also the organizers of an annual lowrider parade through town, a major crowd pleaser that has since evolved into an entire weekend of events.

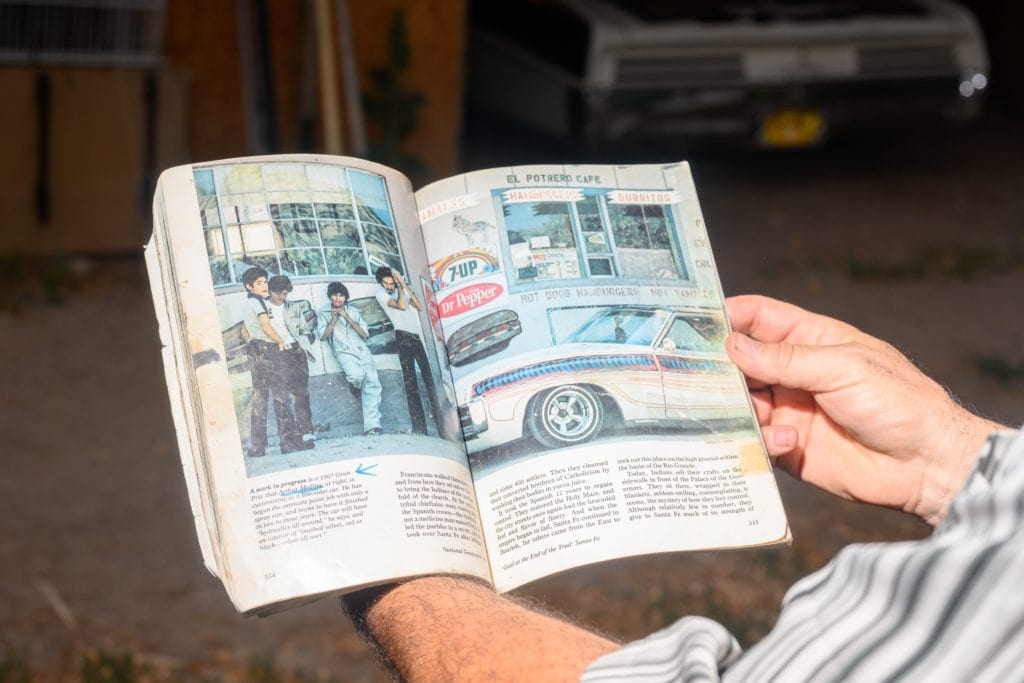

The Medinas have been involved in the scene since at least the early 1980s, and Low Low’s intricately hand-painted cars are well known by locals. His ‘76 Cadillac coupe, “Lowrider Heaven,” is always on display during the annual Good Friday pilgrimage to el Santuario de Chimayó. He even appeared with his first lowrider, a ‘67 Grand Prix, in a 1982 issue of National Geographic.

“I learned completely by doing,” Low Low says. “I was always experimenting with different materials and new techniques, using things just lying around the workshop, like paper plates as stencils for creating paint effects to etching glass. We’re always learning. Even the Smithsonian has asked about my cars.”

The Medina home is tucked into a grove of cottonwoods and fruit trees in Chimayó and is itself a total lowrider heaven. When I visited, a couple of days after this year’s parade, there were no less than a dozen cars at various stages of work. These included an over-the-top ‘88 Chrysler limo, Joan’s jet-age cobalt blue ‘60 Chevrolet, a ‘49 New Yorker straight out of a classic gangster flick, and even a little ‘63 work-in-progress set to become perhaps the world’s first lowrider ice cream truck.

Low Low shows off the details of allegorical panels he painted on Lowrider Heaven. | Photo: Tag Christof

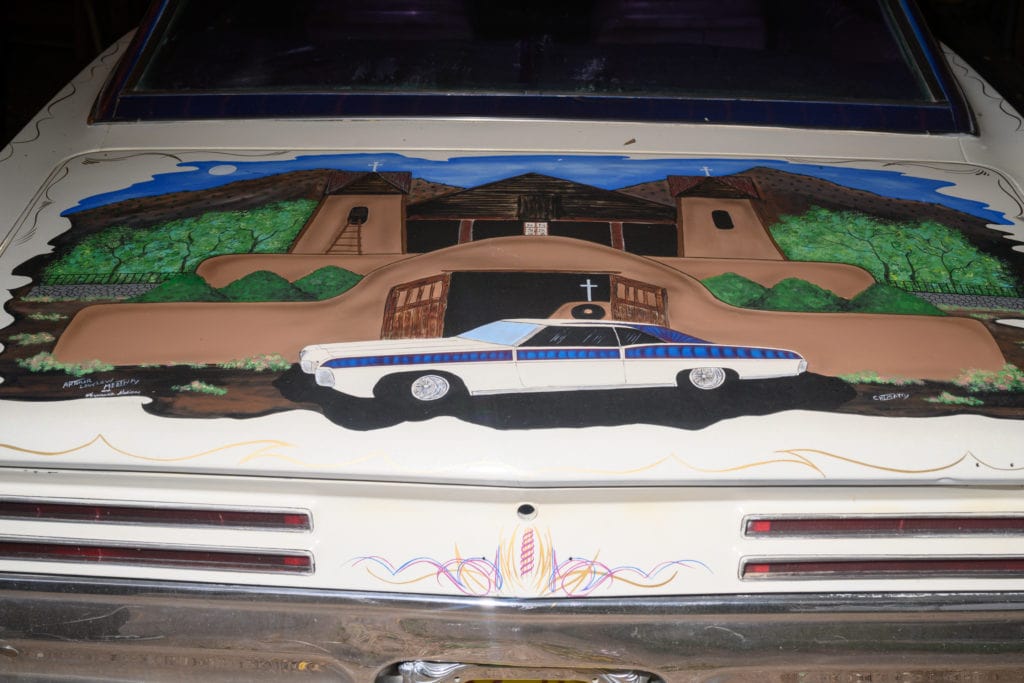

Meta mural on the trunk of the ’67 Pontiac, showing it parked in front of the famous Santuario de Chimayó. | Photo: Tag Christof

Detail of paint work on Low Low’s ’67 Pontiac. | Photo: Tag Christof

Low Low and his Pontiac in a 1982 issue of National Geographic. | Photo: Tag Christof

There’s a pair of ‘67 Pontiacs, an iridescent black one that belongs to their eldest daughter, and “Little L.A.,” that famous original Grand Prix. Low Low once sold it, then fortuitously found it years later and set about restoring it to its former glory. It has gone through at least three major transformations, with the current version showcasing a very meta, hand-painted illustration of itself in front of the iconic Santuario.

There’s also Low Low’s Cadillac showstopper. “Lowrider Heaven” is truly the Sistine Chapel of cars, the result of hundreds of hours of handwork. This Chimayó Michelangelo even tells the story of how he parked the car on the side of a hill, then lay on his back to paint the series of 12 panels that wrap around the base of the body. The entire car is covered with biblical allegories in a lowrider airbrush nod to the Spanish retablos that adorn traditional New Mexican churches, and lend the car an air of the supernatural.

“I started painting from the back, worked my way around, and ended at the back, at Jesus’ tomb,” Low Low says. “As soon as I finished, really, just as soon as I finished, the paint right at the door of the tomb cracked, bro! It actually cracked!”

There is also a neat indoor-outdoor gallery displaying some of Low Low’s works on wood and canvas. Together with their daughters, Anamaria and Marisol, Low Low has been hard at work re-engineering and decking out a vintage cargo truck that will become a sort of mini museum on wheels. Marisol’s hand-drawn artwork will adorn parts of the exterior, while Low Low is working out a system for efficiently displaying art in the cargo bay. “I love to see my husband and the girls working together,” Joan says.

Lowriders are forever

Although it was small in comparison to the inaugural 2017 event, this year’s parade was a hit. Española’s west side main street was closed to make way for a procession of dozens of lowriders. Some tossed candy at spectators, many showed off their hydraulic origami as they bounced by, and every single one looked fantastic.

“These parades remind me of Española’s glory days, back when we could really be proud of our town,” says local resident Carla Abeyta, who watched the parade with her two daughters. “Most people around New Mexico look down on people from Española, but we really have a special, unique culture here. I think we’re learning how to show it off in a more positive light.”

After some fanfare and a pro-lowrider speech from the city’s young mayor, Javier Sánchez, the day culminated in a friendly “hop” competition.

Hop cars are specialized lowriders—rather than the elegant low and slow showstoppers, they place an emphasis on clever engineering skills to bounce the car’s front end upwards for maximum height at the front axle. Small trucks like Ford Rangers and Chevrolet S-10s have traditionally been hop favorites for their lightweight bodies and open beds that make installing complex hydraulic systems more straightforward, but almost any type of lowrider can be adapted. One standout this year was a modified ‘90s Town Car, a massive yacht whose main strength as a hop car was actually its sheer size: When totally vertical, its front bumper towered a couple of feet above the other competitors.

Since the beginning of lowrider time, fashion has gone hand-in-hand with the pageantry of cruising. There’s a heritage uniform of sorts for cholo lowrider style: monochrome oversize t-shirts, bandanas tied just right, and dark sunglasses made personal with some defining flair.

These days, lowrider style also runs the gamut from contemporary streetwear (I spotted Balenciaga, Gosha Rubchinskiy, and plenty of Gucci) to zoot suits and pin-up girls. But the standouts—this year and every year—were members of the OG Veteranas, an all-female car club dedicated to empowering women in what has long been a male-dominated culture.

The OGV’s are strong ladies with impressive rides, who also sport some serious personal style: They all wear matching jewel-studded club necklaces, often combined with gravity-defying hairstyles and over-the-top makeup.

“A lowrider is forever. It’s an heirloom. I got this Bonneville from my grandmother, it’s named Abuelita,” OG Veterana Annette Medina says. “It’s just got these lines and details you can’t find on new cars. When you put so much love and work into a car, it becomes an extension of yourself.”

In a speech just before the hop, youth pastor Ernesto Sena said, “Others have looked down on us for being different, for wearing dark sunglasses that say ‘Loco’ on them. But every single one of us here is proof of the strength of a culture and of a people.”

And as wild applause came from the crowd, there was a palpable sense of pride—of a town that’s been down and out for a generation at last slipping on its bandanas, hopping skyward.

If you go

The annual Lowrider Day parade, organized by the Española Lowrider Association, is held on Plaza de Española one Saturday every July.