Before it went viral through a Craigslist ad in 2013, the Gin Mill was a mostly-forgotten bar in a mostly-forgotten town. It’s one of the few structures still standing in Seneca, a ghost town three hours northeast of Sacramento, California.

Seneca Road, the 6-mile dirt path that leads into town, is intimidating. I stop in nearby Canyon Dam and wait for Mark Burnham and his wife Cynthia before attempting to head down it. They pull up in a raised, red Ford F250 with antennas on the flatbed.

Burnham is the “unofficial mayor” of Seneca. While she was still pregnant with him, his mother took him camping and fishing there, and he’s been coming back ever since. Burnham introduced Cynthia to Seneca when they met 20 years ago.

The dirt road is steep, with no guardrail between vehicles and the 2,000-foot canyon along its edge. “There’s no room for error,” Burnham warns before we start driving. I throw my car into four-wheel drive and lead the way down the road in low gear, nervously clutching the steering wheel while watching for oncoming traffic. From the top of Seneca Road I can see Lake Almanor, the largest reservoir in Plumas County. Burnham describes Almanor as “Lake Tahoe without the people.” A few years ago, he sold his moving company and house in Concord, about 30 miles outside the Bay Area, to buy a cabin and live by the lake full time.

It’s a beautiful drive—slow and nerve-racking, but also serene and scenic. Just before reaching Seneca, we cross a stream. The sound of running water is louder than anything else. We are officially off the grid.

-

One of the wider sections of the road to Seneca. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray -

The edge of the road to Seneca. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray

Cards on the walls

It’s a beautiful, clear, and sunny day on Labor Day weekend, and the Burnhams are hosting a group of former customers at the Gin Mill. They open the sliding door to the bar shortly after 10 a.m.

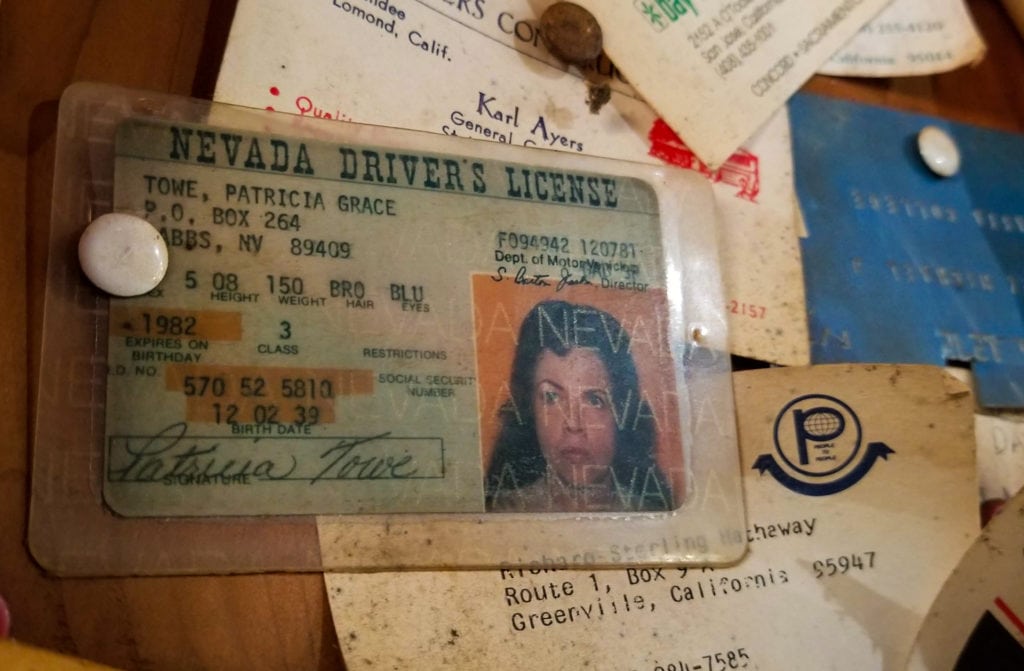

The walls of the small, dimly lit room are covered with business cards, photos, expired credit cards, and other personal memorabilia spanning almost 70 years. Behind the bar sits a couple of old propane refrigerators and a kitchen that hasn’t been used in years. There’s a dusty piano in the corner and a stove that was recently donated.

-

Cards posted on the wall of the Gin Mill. The door leads to a bathroom that is no longer in use. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray -

The old piano in the corner of the Gin Mill. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray -

Drivers license on the wall. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray -

Student ID card posted on the wall. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray

Stepping into the Gin Mill is like traveling back in time. “People come in looking for their cards all the time,” Burnham says as he places some candy on the bar and packs a cooler with soft drinks.

Seneca was established in 1851 during the California Gold Rush. “Gold was found and a wild mining town was born,” reads a plack fixed to a rock just outside the Gin Mill, which was built sometime in the 1930s and expanded during the ‘60s. The actual town of Seneca was situated up the road from the bar, but it was destroyed in a fire in the 1940s.

At its peak, Seneca was home to an estimated 5,000 people. There was a school, church, opera house, post office, several mines, and even a rumored opium den built into the rocks. Burnham says that once, when he was digging through a pile of old, rusted beer cans and debris he calls “the dump,” he found an opium vial.

Today, the Gin Mill is the only structure on the 9-acre property that remains mostly intact. The remnants of old motor homes and cabins are scattered throughout the property. It’s one of the few plots of privately-owned land in the area; the rest is controlled by the Forest Service.

Finding gold

For more than 60 years, beginning in 1934, the bar at Gin Mill was tended by Marie Sabin, known locally as “the guardian angel of Seneca.” Sabin and her husband Don, an equipment operator for PG&E, lived in a cabin up the road. Sabin, who weighed less than 80 pounds, rubbed elbows with miners, outlaws, celebrities, and everyone else who passed through the bar just fine. “She always had a smile for everybody,” says Shirley Friedrichs, who spent her childhood summers in Seneca with her best friend Lynn. “If Marie was at the Gin Mill, you always went down and had a drink with her.”

Before their time, Seneca was a “booming town,” Lynn says. Her great grandfather lived in Seneca and made enough money mining gold to be able to buy a house in San Francisco. He had 13 kids, raising his daughters in the Bay Area while the boys stayed in Seneca to work in the mines.

To this day, Seneca is still a mining town. There are three active gold mines nearby. At one time, there was so much gold in the region, miners often paid for their drinks in gold. So much gold passed through the Gin Mill that you could—allegedly—pay off your bar tab just by scraping the floorboards for gold dust.

According to Burnham, you may still be able to find a small nugget or two of gold in the nearby river (a piece the size of your fingernail is worth more than $1,000 today).

Pee-wee’s big contribution

Over the years, the Gin Mill has had four owners. The original owner, Wendell Snow, founded the place—then a resort—in the 1930s. Back then, the area catered mostly to outdoor enthusiasts and miners, and fishers reportedly drank for free. In the 1960s, the bar was passed on to the Brown family. The Seneca Resort, as it was known at the time, was so popular that its campground had a waiting list several years long—but after a steep increase in gas prices, tourism started dropping off in the 1970s.

One day in 1975, Tim TenBrink, a nurse from nearby Susanville, and Jerry Manpearl, a lawyer from Santa Monica, came across the Gin Mill while on a hunting trip. “The ducks weren’t cooperating. We found drinking was more productive,” TenBrink told the L.A. Times in 2013.

During a card game, the men saw a “For Sale” sign on the bar. “We had about 20 drinks, and then somebody saw a sign and said, ‘Hey, look, it’s for sale,’” TenBrink told the Sacramento Bee the same year. After buying the place, the new owners stopped using the campground and built a stage to host concerts, attracting a hippie crowd that lead to Seneca becoming known as “Woodstock West.”

After Sabin passed away in 1996, the bar was open less frequently. TenBrink and Manpearl both became unable to take care of the Gin Mill due to health reasons, and in 2013, TenBrink’s nephew took it upon himself to list the town for sale on Craigslist. The listing reached Pee-wee Herman actor Paul Reubens, who blasted it out to his 1.5 million Twitter followers. The post went viral, attracting reality TV producers and potential buyers from all over the country.

In between ownership, the Gin Mill and its surrounding area fell into disrepair. Squatters moved in. The porch nearly collapsed, and the interior was looted and filled with trash. A few years ago, the Burnhams lead a restoration effort, sifting through years of trash to separate the business cards and memorabilia from the rubbish to bring the Gin Mill back to life. Along the way they found countless artifacts from the past, like a frying pan that Sabin used to make burgers.

All dried up

Today, the Gin Mill is owned by Jeffrey Vanover, a financial planner living in Houston, Texas. Vanover originally had plans to restore the cabins and re-open the bar but, according to Burnham, he is no longer moving forward with those plans. Much to the dismay of some visitors, the new owner also let the liquor license expire. The Gin Mill was one of the only bars in the county with an active liquor license, and it was arguably the biggest selling point of the property.

But not everybody thinks it’s a bad thing that the Gin Mill is no longer serving alcohol. “I don’t think it should ever be a bar again,” Burnham says. He tells me he’d rather see the Gin Mill evolve into a museum of some kind. Many people agree with him, citing the dangerous road as just one reason for people not to drink before driving home.

-

Candy cigarettes placed on the bar in the Gin Mill. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray -

American flag on the porch of the Gin Mill, Shirley’s truck in the background. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray -

A longtime visitor of the Gin Mill retraces history on the exterior of the bar. | Photo: Lexis-Olivier Ray

While I visit, the closest thing you can get to a beer is a root beer—but that hasn’t stopped people from bringing their own booze.

During the ‘90s, the Gin Mill used to draw a real crowd. “You would come down here and there would be five people, and then before you knew it there would be 200, and then later there would be 600,” says Doug, a former regular who now lives in Ojai.

While there’s only a few dozen people here today, the place still looks and feels like a bar. For some, it’s a reunion—but the bar has served so many people that most of the former customers are just meeting each other for the first time. Each of them is contributing a little bit to the long history of the Gin Mill. The bar may not be serving alcohol anymore, but it’s still bringing people together.

A note from the author

“In early August, 2021, the Gin Mill was destroyed by the Dixie Fire, at the time the second largest wildfire in California history. Mark Burnham told me that he was able to save a hundred or so cards from the walls, the piano chair, the drop-down portion of the bar, and a few other artifacts.”