As I drive along the twisty back roads of Pawling, New York, I expect to see historic homes, mossy cemeteries, and the occasional white-tailed deer. What is, perhaps, less expected is my first glimpse of the Akin Free Library, an imposing stone building designed in the late Victorian style by architect John A. Wood.

The library’s copper cornice and clock tower have long oxidized to a color that vacillates between Statue of Liberty-green and nearly black, depending on the light. And—in what I later realized to be a fitting preview to the collections contained within—the four-sided clock stopped keeping time long ago.

The earliest settlers to the area, located in Dutchess County near the Connecticut border, were Quakers—the Oblong Friends Meetinghouse, built nearby in 1763, still stands today. In 1880, Albert J. Akin founded the The Akin Hall Association with other members of the Quaker Hill community in the service of “charity, literature, science and mutual improvement in religion.”

The cornerstone for the library was laid in 1898, but it didn’t officially open until ten years later. Although the library’s thousands of books no longer circulate, its collection, including beautiful—and increasingly fragile—ledgers from local businesses, can be viewed and handled by request. But to see the crown jewel of the library’s eclectic collection, you’ll have to descend into the building’s basement (and go back about 70 years in the process).

One collector’s vision

When I reach the bottom of a spiraling set of creaky, wooden stairs, the first thing I see is an entire case of colorful, taxidermy hummingbirds, lovingly posed on tiny twigs. To my left is a case of curiosities—four of the felt letters from its “extinct birds” label are long gone, but their impressions remain (as does a passenger pigeon; last seen in the wild in the 1890s, they were extinct entirely by 1914, when Martha, the last captive specimen, died at the Cincinnati Zoo).

Nearby, visitors are encouraged to press a button that triggers a magic trick in a dimly-lit diorama, turning a plump snake instantly into a skeleton (a low-tech but impressive feat accomplished with mirrors). And this is just a tiny fraction of the curiosities that await you in the Olive M. Gunnison Natural History Museum.

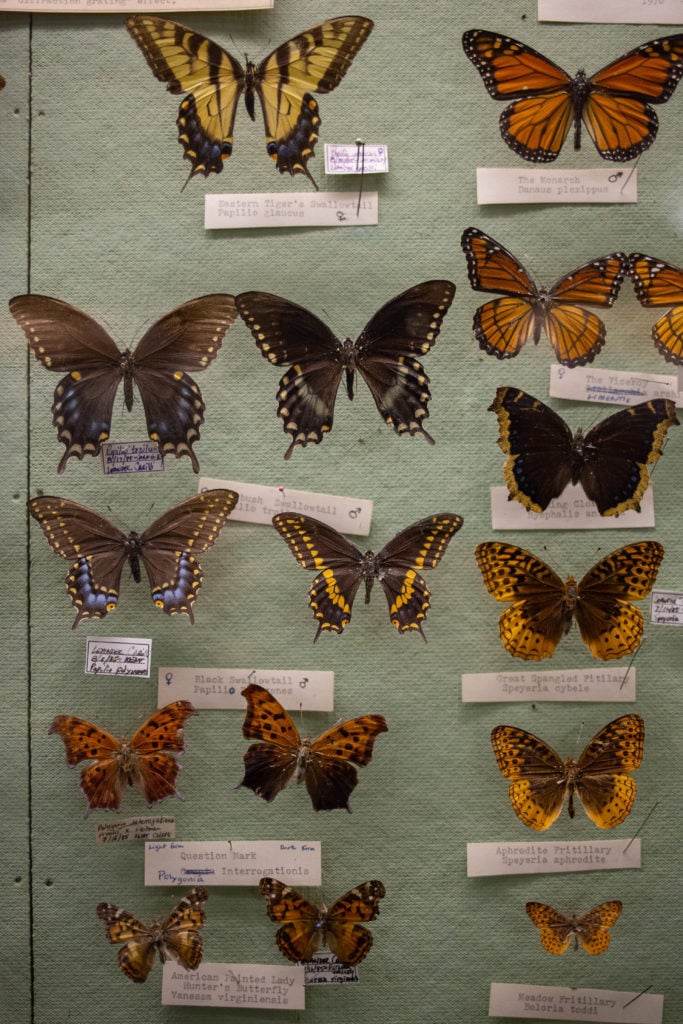

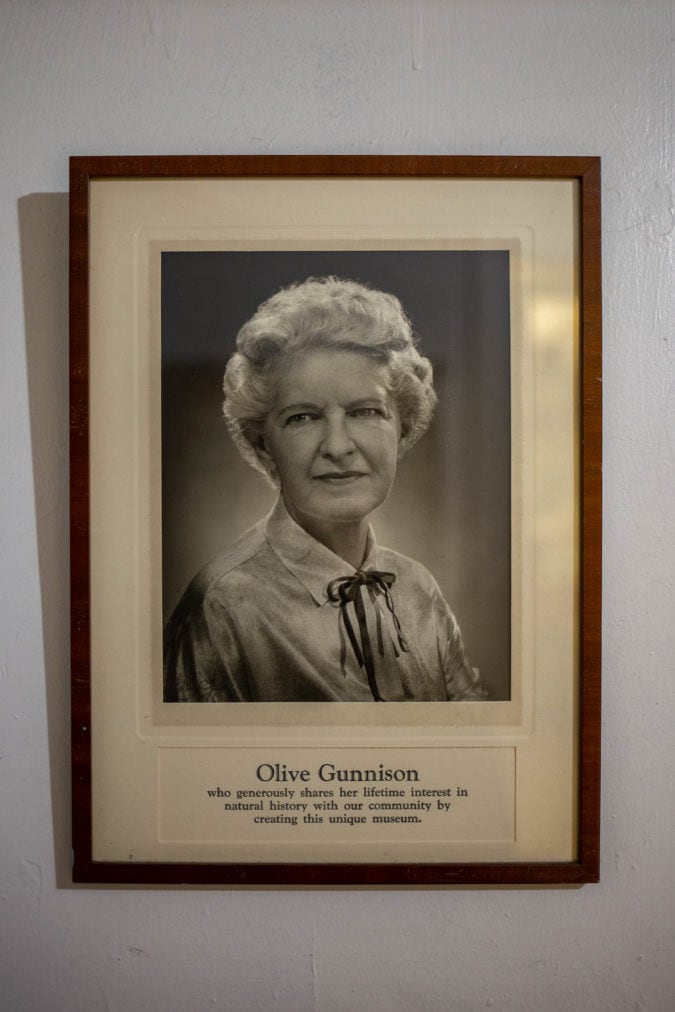

As a child, Gunnison collected insects, mice, and worms—anything she could find outside or fish out of a trap. When she was 12 years old, inspired by her father’s pinned butterfly collection, Gunnison used her allowance to purchase a horned toad, a tarantula, and a piece of red organ pipe coral, beginning a lifetime of collecting—the cumulative result of which is on display in lower level of the Akin Free Library.

By all accounts, Gunnison grew into traditional housewife and mother of three—albeit one with a growing collection of oddities that necessitated building a separate shed behind her home in Pawling. New specimens for this “chamber of horrors,” as her husband called it, were primarily acquired by Gunnison herself with the occasional donation from like-minded friends, including the writer, actor, and world-traveller Lowell Thomas.

“To be complete,” Gunnison wrote, “A museum of natural history should include every branch of interesting subject viz. animals, birds, insects, marine life, minerals, fossils, and other antiquities, artifacts and of course celestial bodies.”

The Gunnison Collection, donated to the library in 1960, fills four rooms, split into two sections: a natural history collection and a cabinet of curiosities. True to her qualifications, the collection comprises a wide range of specimens far too vast to list, but notable items include a shrunken head from Ecuador (whose donor wished to remain anonymous), the footprints of a dinosaur captured in stone, uranium ore, shards from the atomic blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and a mammoth tooth.

The best part of the collection might not even be the specimens themselves, but their descriptions, yellowed with age, composed and typed by Gunnison herself. “I was never content to simply put a label on an exhibit without telling something about it,” she wrote.

Ivory-billed woodpeckers have a fascinating backstory—they are officially listed as critically endangered despite the absence of a confirmed live sighting since the 1940s—but Gunnison’s description is even better: “This is the boss carpenter of the bird world, the biggest, handsomest and rarest of American Woodpeckers. This bird has astonishing strength and vigor. Often beneath a diseased tree which it has attacked in quest of boring beetles or insect larvae, huge piles of bark, slabs of wood are found which give evidence of its power as a feathered axman.”

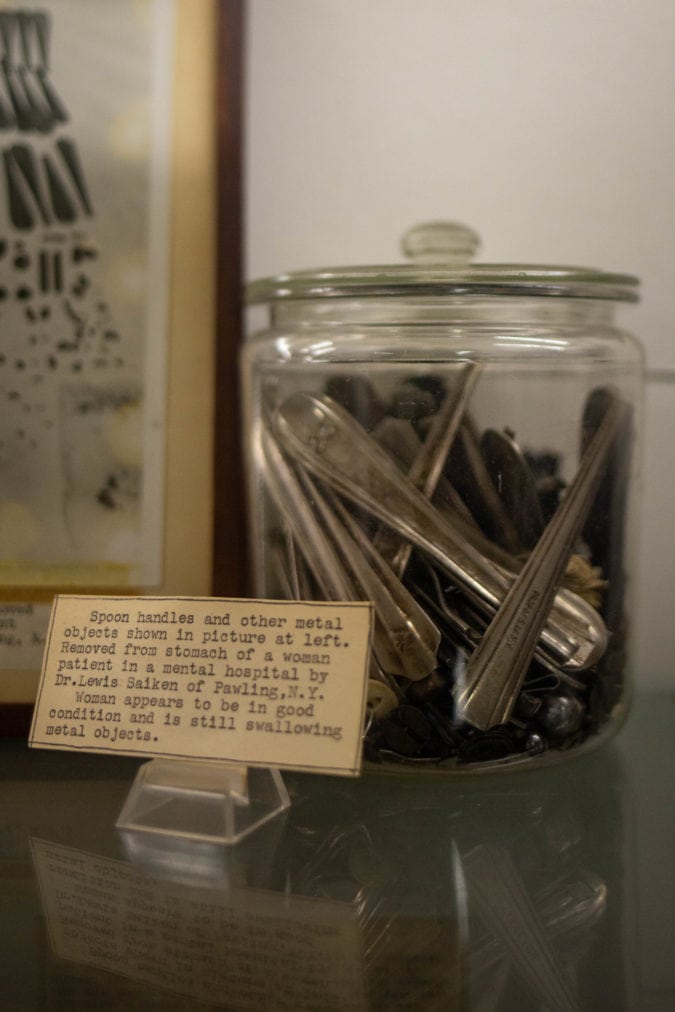

It would be impossible to pick a favorite item on display, but Matthew Hogan, Akin Hall Association Executive Director, makes sure that we don’t miss one that may fall outside the natural history qualification but more than makes up for it in its strangeness: a glass jar containing metal objects (primarily spoon handles) removed from the stomach of a woman residing nearby in a psychiatric hospital.

Gunnison wrote: “Woman appears to be in good condition and is still swallowing metal objects.”

An uncertain future

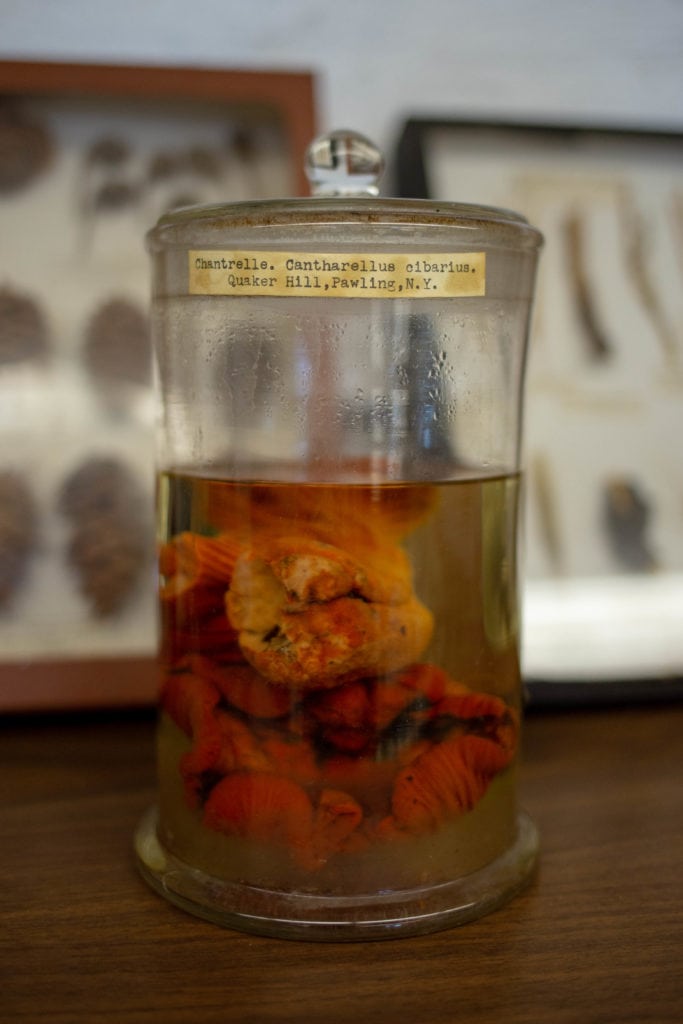

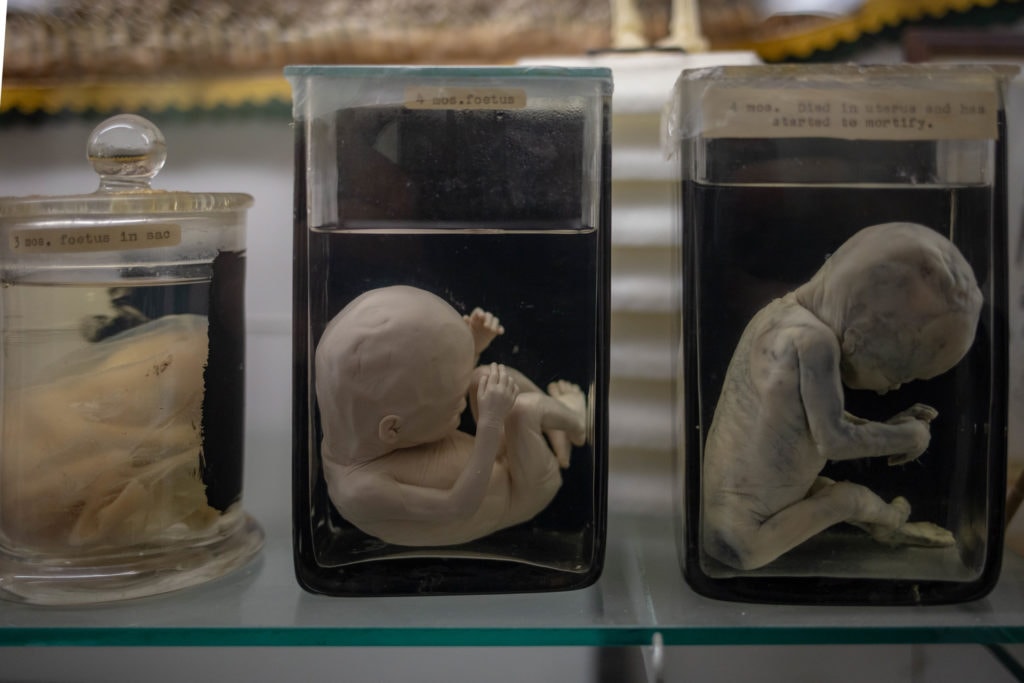

Gunnison was college-educated and always interested in the “ologies,” as she called them, including zoology, botany, geology, and meteorology. In addition to crafting her colorful descriptions, Gunnison prepared all of the wet specimens herself, often using whatever jars she had on hand. (I wonder how Hellman’s would feel knowing that one of their large mayonnaise jars has been helping to preserve an alligator for the past 70 years.)

But chemical preservation processes have evolved over time and due to a combination of her homemade approach, aging materials, and environmental factors, many of the specimens in the collection are in dire need of preservation or in danger of being lost entirely. “The wet collections pose a challenge for several reasons,” says Hogan. “Many of the specimens are desiccated or on their way to drying out due in large part to metal lids—the formaldehyde rusts the metal lids and thus the fluid evaporates.”

Hogan, who has great respect and enthusiasm for the collection, knows that saving it will take time, care, and, of course, money. He estimates that it will cost at least $50,000 to rehab the specimens that haven’t already desiccated—incidentally, it would also be costly to trash the collection entirely, so its future remains in limbo.

“Today, the challenge is care-taking the collection and physical environment, further interpreting the objects, and bringing in local school groups and others,” he says. “We are seeking contributions and experts to help guide the preservation and conservation efforts.”

“Someone once made the remark that people who have hobbies never go crazy,” Gunnison wrote in an essay about her collection. “The reply was, ‘Maybe so, but how about the people who have to live with them?’ In times of a prolonged illness, misfortune or sorrow there is no question but that hobbies do help make life more bearable for everyone concerned and I speak from experience.”

As a woman interested in science and all things curious, Gunnison was probably used to people not taking her seriously—and her husband might have wondered why his wife would rather spend her time preserving a two-headed kitten than making a nice jam. But when visitors would ask Gunnison why she collected so many different things, her reply was simple: “It wouldn’t be a museum of natural history otherwise.”

If you go:

The Akin Free Library is open Saturday and Sunday 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., May through October. Donations to the library can be made here.