As a teenager in the early 2000s, my family and I would sometimes take overnight trips to Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park. From our house in Hāmākua, on the coast of the Big Island, it was a 1.5-hour drive to the rain-soaked forests of Volcano Village. We stayed in a cabin built by friends near an Anthurium farm, in a thicket south of Volcano General Store. Even today, when I hear the word “volcano,” my thoughts go directly to dirt roads choked with foliage and moss-smothered bark, the air heavy with humidity.

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park is as diverse as it is enormous. Just 45 minutes southwest of Hilo, the park is a whopping 323,000 acres of volcanoes, rainforests, lava fields, and craters, with 150 miles of hiking trails. Established in 1916, the park was later designated as a UNESCO International Biosphere Reserve for its geological and biodiversity. It’s home to two volcanoes, Mauna Loa and Kīlauea—one of the most active volcanoes in the world.

During our family field trips, we spent days exploring roads and trails, circling the forested rim of Kīlauea Iki Crater, and deciphering petroglyphs in ancient lava fields at Pu`u Loa. We got up close to the steaming rocks, sulfur crystals, and red clay at Ha’akulamanu—which, thanks to the sulfur, smells of rotten eggs. We stepped into damp lava tubes and spied nēnē geese on roads half-eaten by old flows. My mother, a Hawaiian medicinal practitioner, pointed out herbal plants whenever she spotted them: ‘ie’ie vine blossoms that entwined the trees, the titillating curls of the Hāpu'u fern, and the stalk-like ‘ae fern that peeks through cavities in the lava.

It’s a landscape where life thrives in charred remains and dead fields. To Hawaiians, lava is both a destroyer and mother to new life. With each dark plume and violent eruption comes new land and rebirth.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

Get the AppThe big eruption

In 2018, this assorted landscape changed dramatically. Kīlauea made international headlines with a devastating eruption that lasted more than four months. Up until this point, Kīlauea had been erupting continuously in two places: at the summit since 2008 and in Puʻu ʻŌʻō Crater since 1983. On April 30, 2018, the bottom of Puʻu ʻŌʻō suddenly collapsed as the lava beneath drained away. “There was a giant pink ash cloud that kept coming out of the eastern rift that was really amazing to see,” says Jessica Ferracane, spokeswoman for the park.

On May 4, the big one struck. “I was sitting in my car picking up my lunch from the Volcano House right across the street from my office, and a giant 6.9 earthquake shook,” Ferracane recalls. “I ran to the edge of Kīlauea Caldera and looked around the summit. There started these little rock falls around the crater walls. And I just knew that it was going to be the beginning of a new phase for this volcano.”

From May through September that year, for the first time in history, officials closed the park. Lava carved through the Puna district, destroying more than 700 homes. Large fissures burst out over roads and estates. Tens of thousands of earthquakes shook the region and ripped up pavement.

As the lava continued to drain away from the Kīlauea Caldera summit—the heart of Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park—it collapsed. Giant ash plumes emanated from Halema’uma’u Crater, towering from 5,000 to 10,000 feet high, at one point reaching 30,000 feet. For months, the park became a no man’s land, ravaged by some of the most destructive volcanic activity in the U.S. since Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980.

Forever changed

By early August, lava activity began to decrease and earthquakes returned to normal levels; in September, scientists judged the eruption to be over. Park officials and a special recovery team worked around the clock addressing repairs and running the busiest park in the state.

A few sites are still closed for repairs, like Thurston Lava Tube and Jaggar Museum. But for the most part, despite the destruction, it’s business as usual. Most sites, trails, and campgrounds have been reopened since September 2019. The eruption has also opened new viewpoints and perspectives previously unavailable to visitors.

According to Ferracane, now is a fantastic time to visit. “We have the best air that we’ve had in years,” she says. “There’s very little volcanic gas emanating from the volcanoes right now.” It’s quite a contrast from the smoggy skies and heavy vog (volcanic smog) of the past 30 years.

“The Hawaiian skies are just crystal-clear,” Ferracane says. “And that makes for incredible viewing of the changes on the volcano, super good air quality for hiking. People who come to the park now, who visited it before, can look at the summit and just see these astounding changes.”

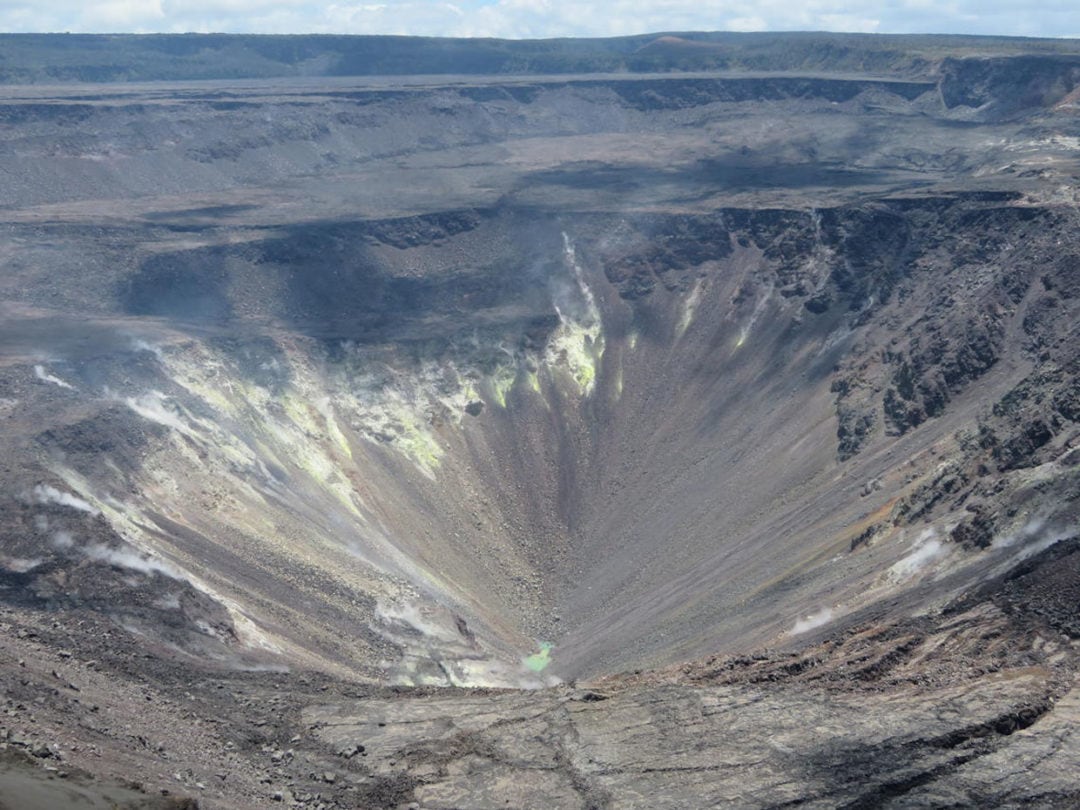

One of the most breathtaking changes is the collapse of Halema’uma’u Crater. When I first visited the crater in the early 2000s, I couldn’t take my eyes off the massive basin, its banks stained yellow from sulfur and billowed with black smoke and sulfur dioxide. The gray valley appeared deceptively sturdy, hiding the seething magma below; beneath me was a lava lake that churned like a cauldron.

William Ellis, one of the first European explorers of the region, described the crater in 1823: “Astonishment and awe for some moments rendered us mute, and like statues, we stood fixed to the spot, with our eyes riveted on the abyss below. Immediately before us yawned an immense gulf, in the form of a crescent … The bottom was covered with lava, and the south-west and northern parts of it were one vast flood of burning matter, in a state of terrific ebullition, rolling to and from its fiery surge and flaming billows.”

Goddess of lava

Halema’uma’u is a spiritual place. According to legend, it’s the home of Pele, goddess of lava. Her power and passion is as famous as her wrath and capriciousness. But she is also known under the name of Pelehonuamea, “She who shapes the sacred land.” She both feasts on and creates new land. My mother always chanted an ‘oli—a greeting to Pele—as she approached the outlook, a sign of respect to the immense power underneath.

Back then, the crater was just a fraction of what it is now—a giant, gaping, cavernous maw. In May 2018, Halema’uma’u's volume was about 70 to 78 million cubic yards. It is now closer to 1.2 billion cubic yards. As the basin collapsed, walls caved in and ash spewed out, smothering everything. Where you once could see the crater and the lava lake clearly, today the base is too steep to see.

The closest you can get now is from the south side, Keanakāko‘i Overlook, about a quarter-mile from where the action happened. Visitors can park at the Devastation Trail parking lot and walk out over the earthquake damage about a mile on the Old Crater Rim Drive. From this vantage point, you’ll be able to see Kīlauea Caldera, Halema’uma’u sinkhole, the remains of Jaggar Museum, and the part of Crater Rim Drive that fell into Kīlauea Caldera. “It’s pretty amazing,” Ferracane says, “This chunk of road with its yellow medium stripe is just hangin on the crater wall.”

At the bottom of the Halema’uma’u chasm—only visible via a webcam—a new addition to the crater has been attracting the attention of both scientists and amateurs. For the first time in recorded history, a pond of greenish water appeared on the basin of the crater. Larger in size than a football field, the scalding hot pond is coughing up sulfur and magnesium with surface temperatures of about 160 degrees Fahrenheit.

Creation and destruction

Crater Rim Drive, the 11-mile road that once encircled the Kīlauea caldera, is surrounded on all sides by reddish dirt and staccato notes of ferns. Though most of the road is now repaired and open, about four miles of the section south of Jaggar Museum were torn apart by thousands of earthquakes. “It’s like the movie Tremors when those giant earthworm monsters just ploughed through,” Ferracane says. “Roads are ripped up—it looks like that. Unrecognizable.”

She stresses that park officials don’t plan to repair it at all, but instead restore the hiking trails so visitors can see the power of Earth up close. “This is why people come to Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park—to see the creative and destructive forces of two of Earth’s most massive volcanoes, and that’s part of the story here,” Ferracane says. “As long as it’s safe for people to walk out there, we want to showcase that. It’s an amazing sight to see.”

"People come to Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park to see the creative and destructive forces of two of Earth’s most massive volcanoes."

The flora and fauna of Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park seem to be unaffected in the wake of the destruction. Rangers haven’t noticed any major devastation to the plants and animals that call the volcano home. Trade winds blew most of the ash southwest, into the more empty Kaʻū Desert. Even with volcanic activity, life survives. ʻOhiʻa trees in particular have the remarkable ability to close their stomata, or breathing pores, during a period of high volcanic gases. Essentially, they can hold their breath until the coast is clear.

Ferns also seem to thrive in the region. The ‘ama’u fern, whose young stalks burn a dull red, is often the first sign of life after a lava flow. The name Halema’uma’u means “house of the ama’u fern.”

One of the more abundant areas that remain unchanged is the bird park, Kīpuka Puaulu. This rainforest is all lush ferns and old ʻōhiʻa trees. My family used to walk the 1-mile trail through the park, trying to spot a colorful kalij pheasant or ‘Apapane honeycreeper. But, whether they were too shy or scared off by our rowdy voices, I never saw one.

I did once see a few nēnē, the world’s rarest geese, indigenous to Hawai’i. Noted for its delicate necks and decorative stripes, there are around 200 to 250 nesting in the volcano area. They’ve become de facto symbols of the park. So far, biologists have not detected any sort of die-off as a result of the eruption.

Look to the future

For most of Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, life goes on as usual. Though much has changed since the eruption, the overall philosophy remains the same: To understand and respect the power of nature, you have to accept its duality of creation and destruction.

January was declared Volcano Awareness Month in 2010, and this year it’s being observed through lectures and guided hikes. As old roads are blocked off and new trails cleared away, even locals who grew up in the area might have to adjust to new challenges. Officials from both the park and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) are keeping a close eye on the active volcanoes. “There’s no doubt that both Kīlauea and Mauna Loa will erupt again,” Ferracane says. “When that happens, we don’t know. But we’re definitely staying in tune very closely to monitor it.”

If you go

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park is open 24/7, 365 days a week. Check the official website to keep up to date on openings and closures of specific trails and sites in the wake of the 2018 eruption.