In March 1960, Loren Coleman watched a film on the Yetis of the Himalayas. When he inquired about the creature (also known as the Abominable Snowman) in school, his teachers were less than helpful. They told him to “get back to work” because “[Yetis] don’t exist.” Coleman decided to conduct his own research, and a lifelong interest in cryptozoology—the study of legendary or unknown creatures—was born.

Over the past six decades, Coleman has written letters, articles, and books about cryptozoology, he has taught at universities around New England, and has conducted investigations in 48 states. As he searched for cryptids (alleged animals such as lake monsters, hairy bipeds, or swamp creatures), Coleman collected more than 10,000 objects.

“People would give me, donate, or sell me cryptozoology items from the beginning and my home became a museum of sorts,” Coleman says. The first item was a flag from Sir Edmund Hillary’s 1960 expedition to collect evidence of the Yeti. In 2009, Coleman’s collection of native art, foot casts, hair samples, models, and other memorabilia opened to the public as the International Cryptozoology Museum (ICM)—the first of its kind in the world.

ICM is located in a strip of shops and restaurants on Thompson’s Point along the banks of the Fore River in Portland, Maine. To reach the entrance of the small museum, I have to walk through a restaurant, Locally Sauced, which serves burritos, nachos, and pulled pork sandwiches.

A revitalized, industrial waterfront featuring craft breweries, an outdoor concert venue, and an ice-skating rink may not seem like the most natural place to find a museum dedicated to a fringe pseudoscience, but that’s the thing with mythical creatures—they pop up where you least expect.

Bigfoot and the Dover Demon

Probably the best-known cryptid in North America is Bigfoot (also known as Sasquatch), and he has an appropriately-big presence at the ICM. I encounter at least three versions of the upright, ape-like creature before I even pay my admission. A carved, wooden totem-style statue sits outside of the museum, and wooden cutouts line the otherwise-sterile hallway that connects ICM to Locally Sauced.

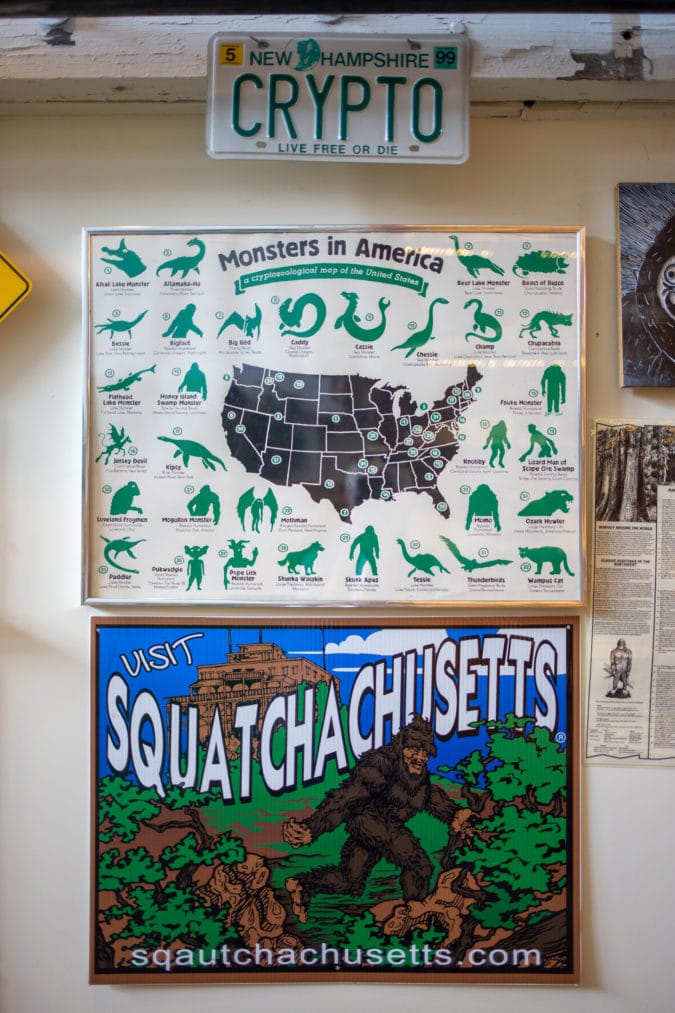

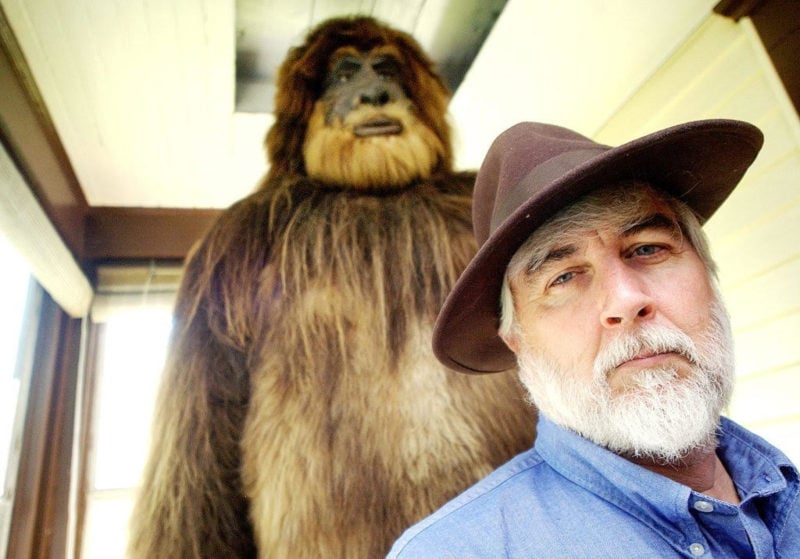

The museum includes several “Bigfoot Parking Only” signs, casts of the creature’s namesake big feet, and numerous dolls and other artwork devoted to Bigfoot. The infamous 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film plays on a loop, and visitors are encouraged to take a selfie with an eight-foot-tall replica. Although Bigfoot is traditionally associated with the Pacific Northwest, a sign urging people to “visit Squatchachusetts” proves that all over the country, people want to believe.

It’s hard to pick favorites, but Coleman has a soft spot for a creature closer to home: the Dover Demon. The small, orange, hairless being was reported by four different people over the course of one week, in Dover, Massachusetts in 1977. It was spotted both sitting on a wall and leaning against a tree. Eyewitnesses described it as having large, glowing eyes and tendril-like fingers. Although skeptics have dismissed the Dover Demon as a foal or a moose calf, “the whole idea of cryptozoology is to be open-minded about the possible discovery of new animals or species,” Coleman says.

While some people are quick to dismiss cryptozoology as a silly pseudoscience, Coleman urges people to not only open their minds, but their eyes and ears as well. Most cryptids had been appearing in folklore and local legends for thousands of years before Coleman brought them to Portland. “Listening to Indigenous people is key,” he says. “Ethno-known information is important, and then you can look for physical evidence.”

Fact is fiction

ICM is billed as “the world’s only cryptozoology museum,” but that’s no longer true. In fact, “truth” is a loose concept within the confines of a museum dedicated to cryptids, the very existence of which haven’t yet been verified by traditional science. A lot of the “evidence” presented in the museum may seem suspect, but the roots of cryptozoology are planted firmly within the realm of provable science.

“Hidden animals with which cryptozoology is concerned, are by definition very incompletely known,” Bernard Heuvelmans wrote in the 1988 journal Cryptozoology. ”To gain more credence, they have to be documented as carefully and exhaustively as possible by a search through the most diverse fields of knowledge. Cryptozoological research thus requires not only a thorough grasp of most of the zoological sciences, including, of course, physical anthropology, but also a certain training in such extraneous branches of knowledge as mythology, linguistics, archaeology, and history.”

You can’t break the rules without first learning what they are, and according to ICM’s website, “cryptozoology is a ‘gateway science’ for many young people’s future interest in biology, zoology, wildlife studies, paleoanthropology, paleontology, anthropology, ecology, marine sciences, and conservation.” As such, the museum also features exhibits on creatures that were once thought to be too fantastical to be real or long since extinct—until actual, live specimens were discovered.

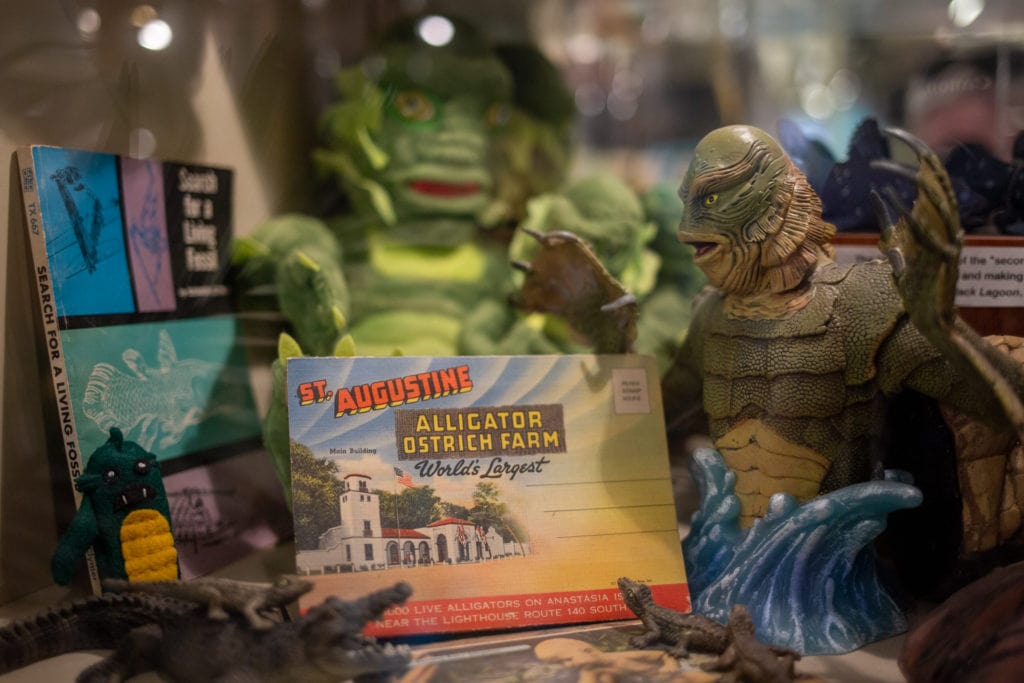

In 1938, fishermen off the coast of Africa discovered a coelacanth, a fish that was thought to have become extinct around 66 million years ago. Between 1938 and 1975, 84 more specimens were caught and recorded, and Coleman’s collection includes the only life-size model of the rediscovered fish displayed in North America. The two-floor museum also includes alleged Yeti hair samples and a FeeJee Mermaid—half monkey, half fish—created for a film about P. T. Barnum, who notoriously loved a hoax.

I want to believe

I have a feeling that P.T. Barnum would have loved ICM—the longer I browse the exhibits, the harder it becomes to distinguish fact from fiction. Since actual artifacts are understandably hard to come by, the museum has several full-sized art sculptures including a Tatzelwurm (a mythical, cat-headed serpent) and a lifesize thylacine (a real-life dog-kangaroo hybrid that is now thought to be extinct).

I try to keep an open mind, but after a few hours spent browsing Coleman’s collection, I wouldn’t exactly consider myself a cryptozoology convert. However, everything known was once unknown, which seems to also suggest the opposite: With enough time and evidence, anything unknown can presumably become known.

“Cryptozoology is all about patience and passion—and so is the museum,” Coleman says. “People enjoy themselves if they come visit to allow new ideas in. The museum teaches critical thinking but also open-mindedness.”

-

The elusive Fur Bearing Trout. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Another depiction of Bigfoot. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Bigfoot signs. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A collection of skulls. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Bigfoot or giant ape? | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Footprint casts. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Various examples of scat. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Cryptozoology-inspired labels. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A Fiji Mermaid. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Swamp creature memorabilia. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

If you go

From Labor Day until Memorial Day, the International Cryptozoology Museum is open Mondays, Wednesdays, and Sundays, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., and Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 6 pm. It is closed on Tuesdays.