We love a good state park, but few can boast as much insane history as Martin County’s Jonathan Dickinson State Park. And we don’t use the word “insane” lightly. From its days well before America was a country (let alone before it was a state park) when shipwrecks were common along the Florida coast, to the early days of Florida’s tourism industry—when visitors would boat up the wild and scenic Loxahatchee River to meet a gator-wrestler who lived on its shores—to its once-hidden history as a top-secret military training school, the park is filled with subtle reminders of its storied past.

So, book a campsite, rent a canoe, lace up your hiking boots, and get ready to explore the story of America’s past, as told by its wildest state park.

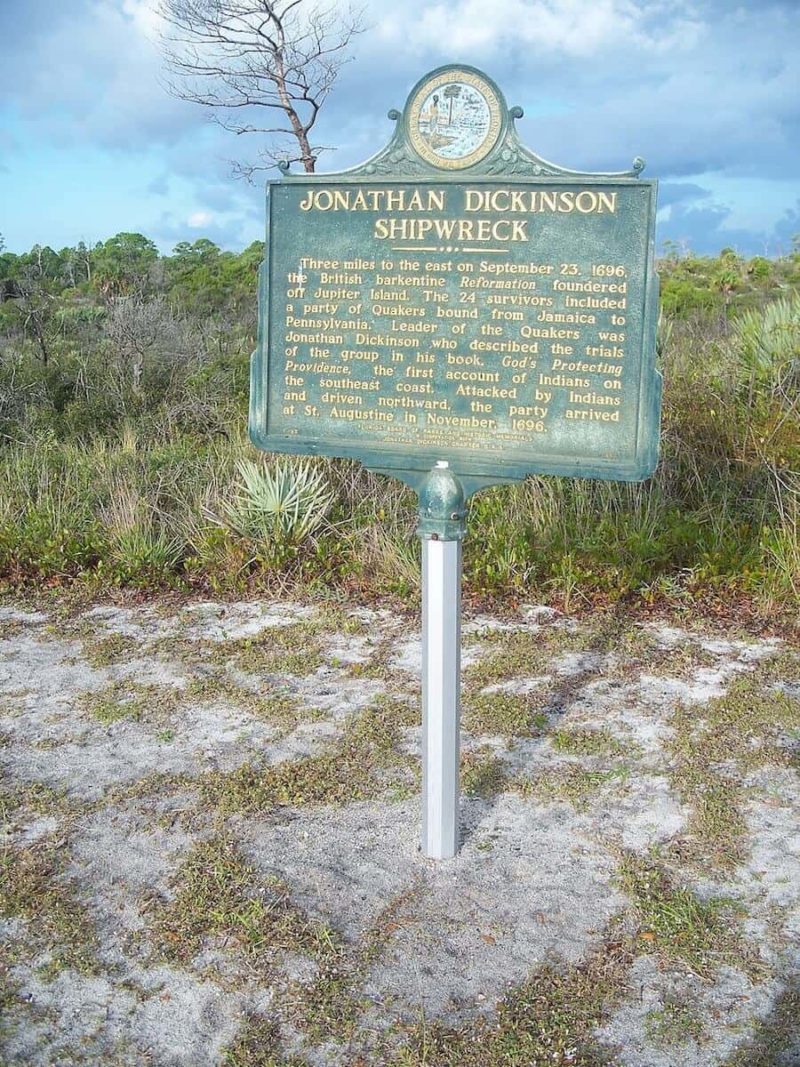

Jonathan Dickinson: The wreck of the Reformation

Jonathan Dickinson was a well-to-do Quaker merchant who was living in Port Royal, Jamaica, with his family, when a devastating earthquake struck the island in 1692. Suffering financial losses after the disaster, he eventually made the decision to move his family to Philadelphia. The story of how a state park in Florida, nowhere near Pennsylvania, came to bear his name is a pretty crazy one.

In 1696, Dickinson and his family set sail on a barkentine called the Reformation. The ship, which had a small crew and several other passengers, became separated from the rest of its convoy. Then, to make matters worse, a storm blew it ashore just north of Jupiter Inlet near Hobe Sound.

Everyone survived the wreck and started saving what supplies they could, but many were sick or injured from the perilous journey. Jobe Indians found them, took their goods, and threatened them, but eventually brought them back to the Jobe village. After a few tense days, the Jobe Indians released the castaways, and they started up the coast to the Spanish settlement of St. Augustine.

But this part of the trip wasn’t smooth sailing, either. The Ais tribe in Santa Lucea detained them again, and then sent them to the town of Jece. Here, they met up with survivors from another ship from their convoy that also wrecked. Finally, at long last, Spanish from St. Augustine arrived to escort them back to the city; the journey remained difficult, though. Food was scarce and conditions were brutal, and several people died of exposure on the journey. Despite this, the entire Dickinson family made the final leg of their journey, from St. Augustine to Philadelphia, where Jonathan Dickinson prospered. He published a journal detailing the shipwreck and journey to Philadelphia in 1699.

Trapper Nelson: Tarzan of the Loxahatchee

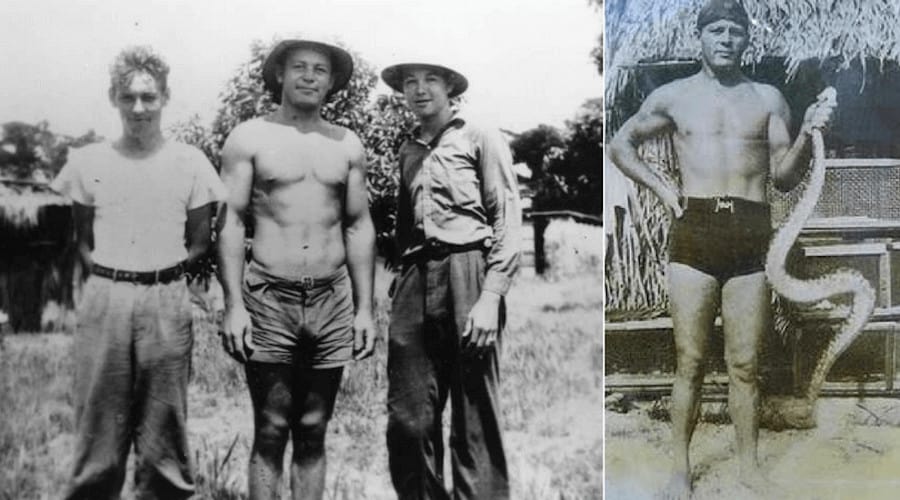

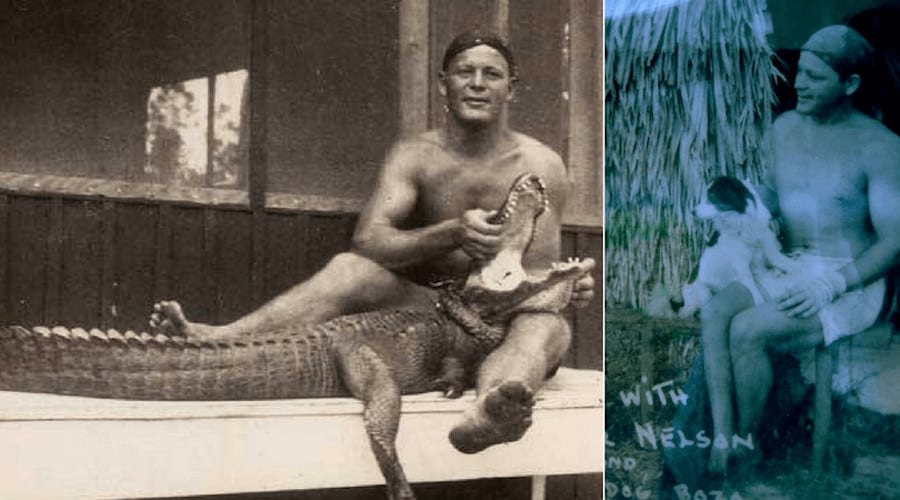

Even more interesting than the history of how Jonathan Dickinson State Park got its name is the story of where the land for the park came from. A good chunk of it came from an eccentric man who was famous for his gator-wrestling, among other things. Trapper Nelson was born Vincent Nostokovich in New Jersey, but ran away from home at an early age. He hopped trains across Colorado and into Mexico. Here, he was arrested for suspected gunrunning, but Nelson, a big eater, was allegedly released because he “wrecked the jail’s food budget.”

After his release from prison in Mexico, Nelson gambled his way to southern Florida, where he, a friend, and Nelson’s stepbrother set up camp on the banks of the Loxahatchee River. Sadly, Nelson’s stepbrother murdered their friend by shooting him in the back. Disturbed by this, Nelson testified against his own stepbrother during the murder trial, sending him to jail. With his friend dead and his stepbrother in jail, Nelson found himself alone, depressed, and distrusting of others. He borrowed some money and bought 800 acres of land deeper in the forest.

He earned money trapping animals and selling the fur, and began to acquire more land at Great Depression-era auctions. He made money when the trapping season was off with “Trapper Nelson’s Zoo and Jungle Gardens,” aimed at tourists taking boat trips along the river from West Palm Beach.

Trapper Nelson quickly gained notoriety as a local celebrity of sorts. Floridians and tourists alike watched him wrestle alligators. He brought exotic animals to parties and could trap any wild animal that was giving anyone a problem. Trapper Nelson was a great help to anyone caring for exotic pets. He was also known for his many lovers and his ever-impressive eating habits. It was normal for him to eat entire pies and 18-egg omelets during a meal. He was drafted into the army during WWII. Luckily, he wound up at Camp Murphy, right near his land (more on Camp Murphy in a minute). After the war, he continued to invest in real estate, but a health inspector visiting his zoo deemed it unhygienic and forced its closure in 1960.

This was the beginning of a dark period for the Tarzan of the Loxahatchee. Nelson spiraled into depression, his health began to fail, and he grew deeply paranoid about the government. He installed padlocked fences across his property, put up signs that claimed the land was riddled with land mines and dammed up rivers so boats couldn’t pass through. He went to town once a week to check his mail and pick up steaks, but wouldn’t allow friends to visit without sending him a postcard to ask permission first.

One day in 1968, he failed to show up to a planned meetup with a friend. His body was found in his cabin. He had died of a gunshot wound to the torso. His death was ruled a suicide, but the fact that it would have been difficult (possible, but difficult) for him to shoot himself in the stomach lead some friends to believe that foul play was the cause. His land is now part of Jonathan Dickinson State Park: the Trapper Nelson Zoo Historic District. To this day, rangers preserve the remains of his camp, including his cabin, a guest cabin, a chickee shelter, docks, a boathouse, fruit trees, and assorted cages from his zoo.

But this eccentric character’s legacy continues to live on. In 1986, park rangers discovered his “treasure.” A well-placed hiding spot in his chimney concealed 5,005 coins totaling $1,829.46. Of course, rangers searched the camp, turning up nothing else… but who knows? There could be more surprises from the Tarzan of the Loxahatchee hidden around his old zoo at Jonathan Dickinson State Park.

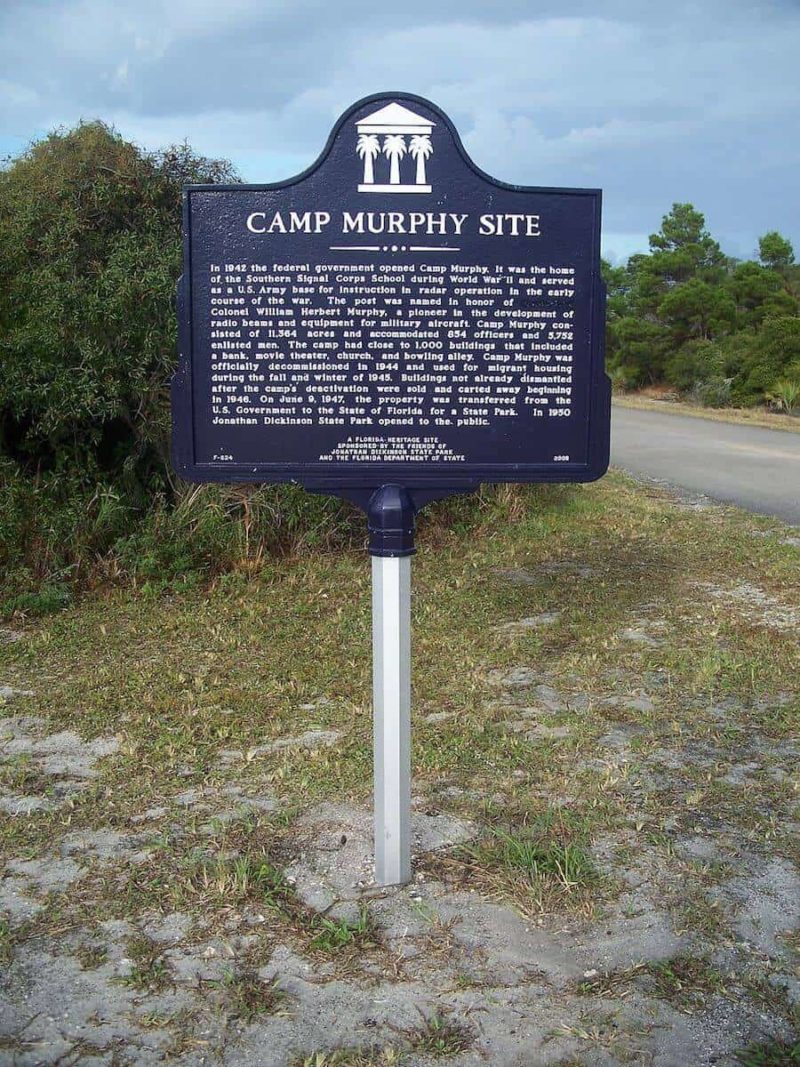

Camp Murphy: Declassified Government Secret

Trapper Nelson’s zoo isn’t the only historic site in Jonathan Dickinson State Park. You can also tour the remains of Camp Murphy, a top-secret training base. Trapper Nelson himself spent some time here during WWII. The army opened the camp in 1942 as a top-secret radar training school. Colonel William Herbert Murphy, a pioneer in the development of radio beams and equipment for military aircraft, is the camp’s namesake. Soldiers who were preparing for “jungle warfare” trained here too, thanks to the dense forests.

In the two years Camp Murphy was operational, it housed 854 officers and 5,752 enlisted men, and consisted of nearly 1,000 assorted buildings. The camp even had a bank, a movie theater, a church and a bowling alley. After the war, starting in 1945, it was used as migrant housing, and in 1948, the buildings were torn down or sold and carted away. Only a few remain, although eagle-eyed visitors can spot the foundations of others. You can even still see the two-room walk-in vault from the bank’s foundation.

The bank vault isn’t the only remains you can explore. One of the park’s campsites is located where the hospital stood. The park’s office is in a formerly-secret bomb shelter for Kennedy administration government officials. You can see an old ammo dump, and the old barracks are still standing as well. You might even be able to find bullets near the old gun range walking south from the railroad tracks. The state took over the camp’s land in 1947, and Jonathan Dickinson State Park opened in 1950.

Jonathan Dickinson State Park Today

In addition to camping and historic sites, Jonathan Dickinson State Park provides a wealth of other recreational opportunities. Take a guided boat tour of Trapper Nelson’s homestead, or enjoy the trails on foot or bike. Paddle a canoe or kayak along the Wild and Scenic Loxahatchee River, camp out, learn from the exhibits in the Elsa Kimbell Environmental Education and Research Center, and/or climb the wooden observation tower for sweeping views of this fascinating gem of a park.