Perhaps Kansas isn’t the first location you think of when imagining a battle between giant prehistoric sea creatures—but it should be.

Key Takeaways

- Kansas once sat under the Western Interior Seaway 80 million years ago, leaving dramatic Niobrara chalk fossils.

- A strange fossil holds a 6-foot Gillicus fish, now fossilized in its stomach still today.

- At KU’s Earth center, a 45-foot mosasaur chases a sea turtle whose shell shows 100 teeth marks.

Kansas Fossils Tell a Wild Story of an Ancient Inland Sea

As a child growing up in the Midwest, my grandparents showed me a small jar of shark teeth they’d collected at a quarry in a nearby farmer’s field. Looking across the gently rolling hills with the only water in sight in a small pond, it was hard to imagine giant marine predators swimming around our land-locked part of north central Kansas. But my grandfather told me that Kansas—along with much of the rest of the Midwest—used to be covered by a sea, millions of years ago.

The Western Interior Seaway and the Niobrara Chalk in Western Kansas

That Cretaceous sea, also known as the Western Interior Seaway (WIS), covered much of the middle of North America about 80 million years ago. Plenty of gnarly creatures ate, fought, hunted, foraged, and died there, leaving their remains for fossil hunters to find millions of years later.

Those remains are strewn across the Niobrara chalk beds found in western Kansas, which are famous for their dramatic sea creatures, according to Rex Buchanan, director emeritus of the Kansas Geological Survey. “In any major museum in this time period, look at the marine Cretaceous stuff and it will be from Kansas,” he says. Some of those fossils came from professional fossil hunters and some from amateurs. The same thrill of the hunt that captured my grandparents’ imaginations has inspired Kansans for a long time.

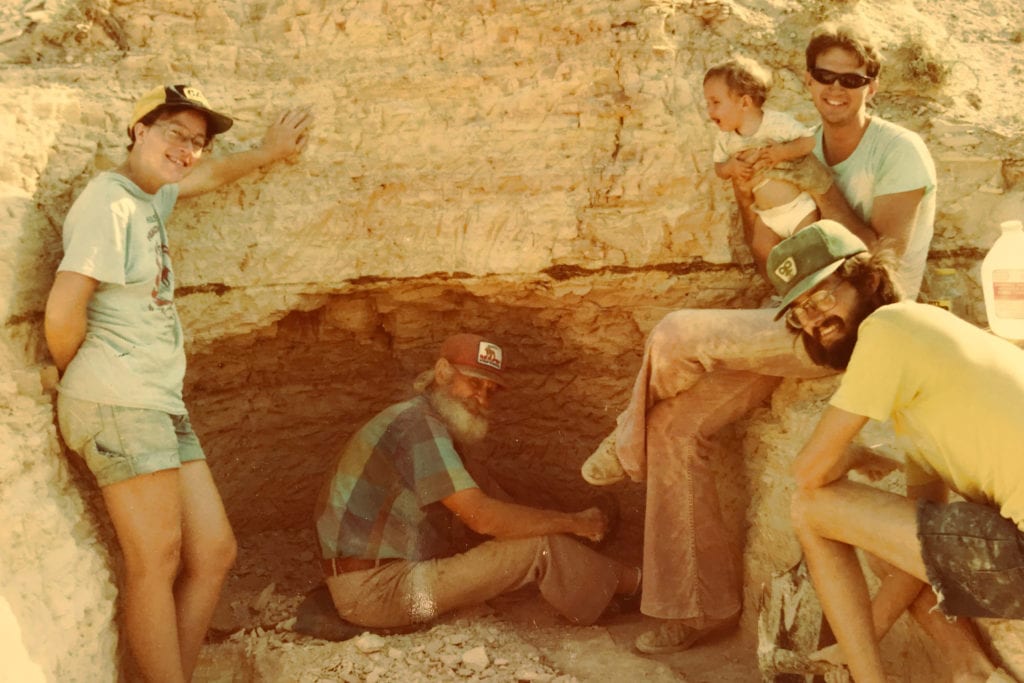

A Kansas Fossil-Hunting Family Tradition in the Chalk Beds

The Bonner family lived in the Leoti area in western Kansas. In 1925, Marion Bonner found a fossilized fish skull on a high school field trip and was immediately hooked. Over the years, Bonner, his wife, and their eight children spent countless weekends picnicking and fossil hunting in the great chalk beds of western Kansas.

Keystone Gallery Near Oakley, Kansas: Fossils, Art, and a Gift Shop

Today, Marion’s son Chuck Bonner runs the Keystone Gallery with his wife Barbara Shelton. The combination art gallery, fossil museum, and gift shop is south of Oakley, about 20 miles off of Interstate 70. “As a kid, the first thing I found that excited me was a fish skull,” Bonner says. “The older I got, the better I got at knowing what to look for.” He found his first fossil around age 5 and decades later, the thrill is still there. “You don’t give up your desire to find the next fossil,” he says.

The Fish-Within-a-Fish Fossil, Xiphactinus and Gillicus

The family tradition didn’t just hit Chuck. His older brother Orville was head preparator at the University of Kansas (KU) Museum of Natural History (now the Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum) and collected, studied, and preserved a multitude of fossils over the years. Another brother, Dana, found a rare fish-within-a-fish fossil: a 14-foot Xiphactinus that probably choked to death when it ate a 6-foot Gillicus fish, now fossilized in its stomach. You can find it on display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Canada.

Kansas Was Covered by More Than One Ancient Ocean

While the rock quarry my grandparents hunted didn’t hold the giant Cretaceous creatures found in the western chalk beds, the shark teeth they gathered likely came from the same time period. But all across Kansas, other sea creatures can be found. “Don’t think of that Cretaceous ocean as the only one,” Buchanan says. “Kansas has been covered by a series of oceans.”

Pennsylvanian Fossils in Eastern Kansas: Brachiopods, Corals, and Trilobites

What Fossils Show up Most in Eastern Kansas

If you’re fossil-hunting in eastern Kansas, you’re more likely to find fossils from the Pennsylvanian time period, around 300 million years ago. “[If you] want to go somewhere today that looks like what Kansas was like in Pennsylvanian time, [it’s the] Florida Keys,” Buchanan says. The shallow waterways are teeming with invertebrate life like brachiopods (an ancient shellfish similar to a mollusk), corals, and the occasional trilobite (a marine arthropod that looks a little like a roly-poly bug).

Fossil Hunting in Kansas: Where to go and How to do it Safely

Safe Road Cuts, Public Land, and Permission Rules

So how do you get started on your own family fossil-hunting adventure? Ancient creatures left their mark all over the country, so you might be able to find something in your neck of the woods. Buchanan suggests watching for road cuts on highways, then exiting onto smaller country roads nearby to find a road cut that’s safe to access. Of course you need to be careful of traffic, and don’t hunt on private property without permission.

Melvern Lake Fossils: Brachiopods and Bryozoans

In eastern Kansas, try hunting near Melvern Lake off of U.S. Highway 75. You can find a few safe places on public land to look for lifeforms from the Pennsylvanian seas, including brachiopods and bryozoans (coral-like invertebrates with tentacles extending from a hard shell).

Clinton Lake Spillway Near Lawrence: Easy Fossil Spotting

Near Lawrence, you can try the spillway at Clinton Lake, a car-free zone with a broad walking path. Sandy shales along the spillway’s edges hold invertebrates. Sometimes fossils just “weather out” and you can pick them up off the ground. You might even find a brittle sea star if you’re lucky.

Kansas Fossil Museums with Prehistoric Sea Creatures on Display

KU Museums in Lawrence: Mosasaur and Sea Turtle Display

If cultivating your patience by searching for traces of fossils in the wild isn’t your speed, Kansas is full of natural history museums with amazing specimens on display. In Lawrence, in KU’s Earth, Energy, and Environment Center, a 45-foot mosasaur darts after a giant sea turtle racing for its life. The turtle’s fossilized shell is covered in more than 100 teeth marks. Spoiler alert: It didn’t get away. The installation is a model of fossils housed in the nearby Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, another fine place for fossil-viewing. Both the mosasaur and the turtle were collected in the western Kansas chalk beds.

Keystone Gallery and Oakley-Area Fossil Stops

Out west, the Keystone Gallery houses some beauties collected by Bonner, Shelton, and other members of their family. You can find fossils and folk art made from ancient teeth and bones at the Fick Fossil Museum in Oakley. Much of their collection was donated by Vi and Ernest Fick who collected specimens on their land in the 1970s.

Sternberg Museum in Hays: Huge Fossils and Life-Size Dinosaur Replicas

And, of course, the flagship institution for fossils in western Kansas is Fort Hays State University’s Sternberg Museum of Natural History where you’ll discover countless fossil specimens and walk among life-size dinosaur replicas.

Why Fossil Hunting Feels Like Time Travel in Kansas

Fossil hunting is a fascinating way to connect with the deep history of a place and imagine how different the world looked millions of years ago. Find a good spot, bring a picnic, and maybe if you’re lucky, you’ll even find a shark tooth or two.