On a sunny and crisp fall afternoon, I park my car on the corner of East 66th Street and Lexington Avenue, just steps away from League Park in Cleveland, Ohio. I’ve booked a private tour of the Baseball Heritage Museum, located inside of a historic building that once housed League Park’s ticket office.

In its heyday, League Park set the stage for numerous memorable moments in baseball history, including the Cleveland Indians’ first-time World Series win in 1920 and performances from iconic players such as Babe Ruth, Cy Young, Bob Feller, and Ty Cobb. With so much history surrounding it, I’m almost certain that if I venture out onto League Park’s pristine, green field right now, I’ll be immediately transported back in time.

Instead, I make my way up to the park’s entrance while scanning the residential area that borders the field. For a baseball fan at the turn of the 20th century, living in Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood would’ve been an absolute dream—minus the occasional broken window.

Preserving the stories of baseball

Inside, my tour begins with one of the museum’s docents recounting Babe Ruth’s 436th home run, which was hit here at League Park in 1928. As I listen, I can almost hear the crack of the bat reverberating over the roofs of the suburban homes that populate the neighborhood, the crowd roaring with excitement as the ball sails over the 40-foot right-field wall—not far from where my car is parked today.

Children rushed toward the field to try to see which player had, quite literally, knocked it out of the park. Twenty-year-old Cleveland native Connie Long was walking home from work along Lexington Avenue when the home run ball landed on the sidewalk with a powerful thud, and she was lucky enough to snag it. Babe Ruth graciously signed the baseball for Long after the game, and the keepsake stayed in the Long family for years before making its return home to League Park in 2018 as part of a permanent display.

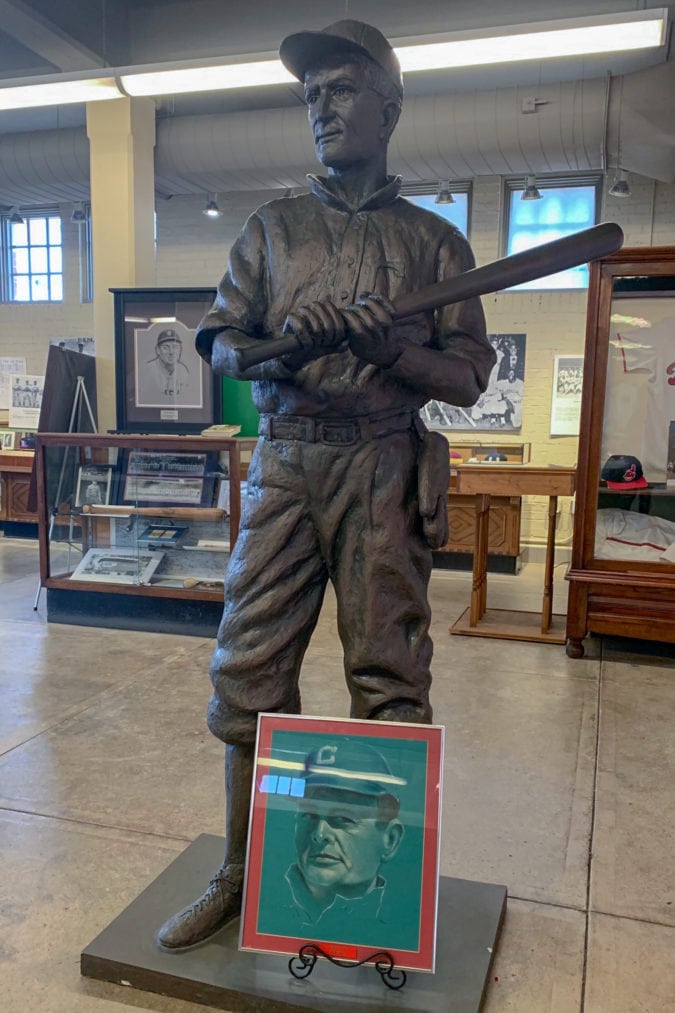

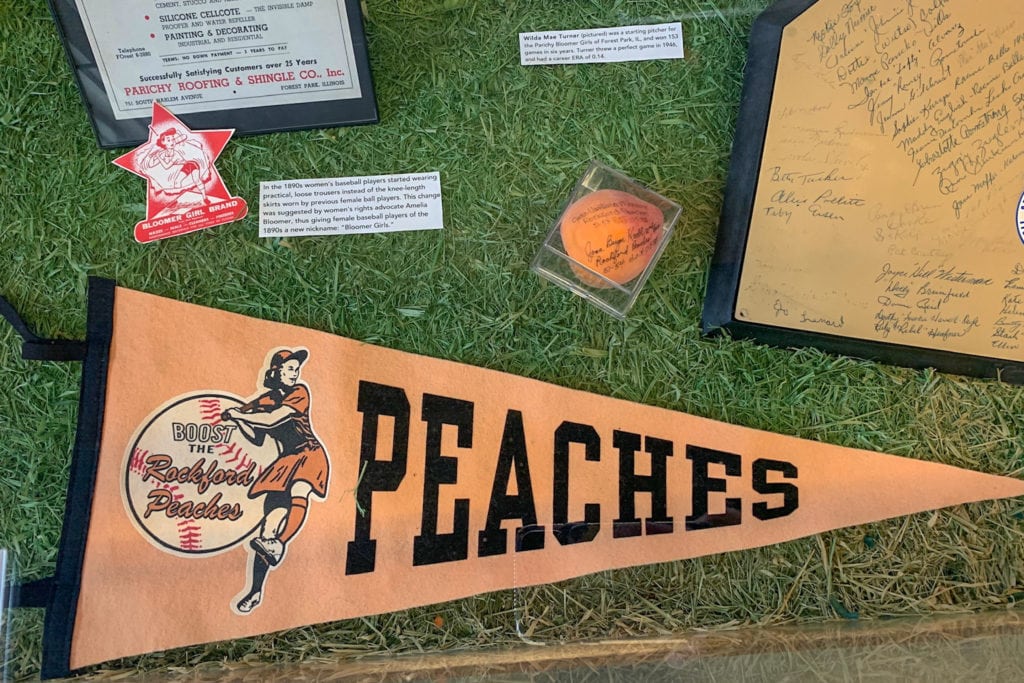

Little-known nuggets of history like this are exactly what Bob Zimmer, founder and director of the museum, is interested in preserving through the educational exhibits he puts together. Since originally beginning his collection of baseball memorabilia back in 1997, Zimmer has continually delivered incredible stories at the intersection of Cleveland and baseball history with each thoughtfully curated addition. Most exhibits at the museum intentionally highlight the largely untold stories of the Latin, Caribbean, Negro, and Women’s leagues that helped shape the great American pastime that we know today.

“We focus on preserving the history of the game outside of the major leagues,” Zimmer writes on the museum’s website. “Through exhibits, programming, neighborhood outreach, and youth education, the museum keeps these stories alive and inspiring for present and future generations.”

Hough’s turbulent history

Often referred to as the birthplace of Cleveland baseball, League Park served as the home of the Cleveland Indians for decades. After the team officially moved to a different field in the 1940s, the city attempted to keep its legacy alive by hosting the Buckeyes, Cleveland’s Negro league, and various little league games on the field when they could. The intentions were good, but the efforts weren’t enough to keep the park open. League Park became worn out and run-down, officially closing its doors to the public in 1946. The park’s iconic grandstands were demolished in 1951.

As the beloved ballpark fell into disrepair, so did the neighborhood surrounding it. A drive through Hough in the early 1900s would have provided nothing but ample views of an industrial city. Bustling commercial buildings lined the streets, while rows of Victorian mansions on Euclid Avenue served as home to some of the city’s most affluent Clevelanders; however, it seemed that Hough’s heyday was somewhat short-lived.

“Hough was a very prominent neighborhood where all of the influential people lived, but after World Wars I and II, the neighborhood dynamic changed completely,” says James Blockett, one of the museum’s docents. “It started to see the effects of The Great Migration and low-income families moving here, which really put a strain on the neighborhood.”

July 1966 marked the neighborhood’s lowest point when the Hough Riots broke out due to intensifying racial tensions and community unrest. The event, which lasted six days, ultimately caused the deaths of four Hough residents, 30 injuries, and hundreds of arrests. A neighborhood that once boasted wealth and vivacity was left wounded.

Luckily, Hough ended up finding a powerful advocate in the years to come. Cleveland councilwoman and civil rights activist Fannie Lewis, the city’s longest serving councilwoman, implemented a new urban renewal plan for Hough in an attempt to bring hope to the struggling suburb and restore it back to its original prominence. “A lot of the neighborhood was destroyed, but she didn’t want it to be recognized for just the riots,” Blockett says.

And as Hough’s future began to look brighter, League Park saw a resurgence of its own. The city of Cleveland put forth $6.4 million dollars for the park’s restoration, and after years of work, League Park reopened its doors in 2014 along with the Baseball Heritage Museum. In its new home, the museum is physically positioned to tell baseball’s stories of hardships and perseverance within the context of a neighborhood whose own history has many parallels.

“The museum is presented with the opportunity to become a community anchor in the neighborhood’s revitalization,” says Zimmer. “We’re committed to expanding its presence and service to the neighborhood and the community.”

League Park today

Following the CDC’s COVID-19 guidelines, the museum is currently closed indefinitely for the health and safety of its staff and visitors, but plans are in place to make a powerful comeback when the time comes to reopen.

At the top of the list is a new exhibit, titled Tragedy to Championship: the 1920 World Series, which celebrates the 100th anniversary of the Cleveland Indians’ first World Series win at League Park in October, 1920.

“We’ll have period baseballs, bats, and mitts on display, and we’ve acquired three images that had been previously unpublished from that actual World Series game,” says Ricardo Rodriguez, the museum’s assistant curator. “We’ve been in touch with the National Baseball Hall of Fame to see if they have any other images we can get reproductions of, but they don’t have any—so that puts us in a really cool position that we do have them.”

The museum is also continuing work on digitizing its extensive image collection in collaboration with the Cleveland Public Library, and, most importantly, exploring the important historical context that accompanies each and every exhibit, photo, and individual artifact they continue to curate.

“As a curator, it’s important to look at what was going on globally at the time, like the roaring ‘20s or entering the World Wars,” Rodriguez says. “History repeats itself, and I implore people to look past the crack of the bat and the hot dogs to find those social and political connections that baseball history really offers.”

If you go

Many locations are currently closed due to the spread of COVID-19. Please contact the Baseball Heritage Museum directly for the latest information, and stay safe.