While serving as a medic in World War I, Sir Harry Andrews contracted spinal meningitis. Paralyzed, blind, and unable to speak, Andrews was declared dead and sent to the morgue. According to Fred Russell, a member of the Knights of the Golden Trail (KOGT) brotherhood later founded by Andrews, doctors began to perform an autopsy. They stopped when Andrews’ mouth began to bleed. “Dead men don’t bleed,” Russell says. Andrews was given adrenaline, an experimental drug at the time, and his heart began to beat irregularly. He wasn’t expected to survive more than a few days, but he lived 63 more years.

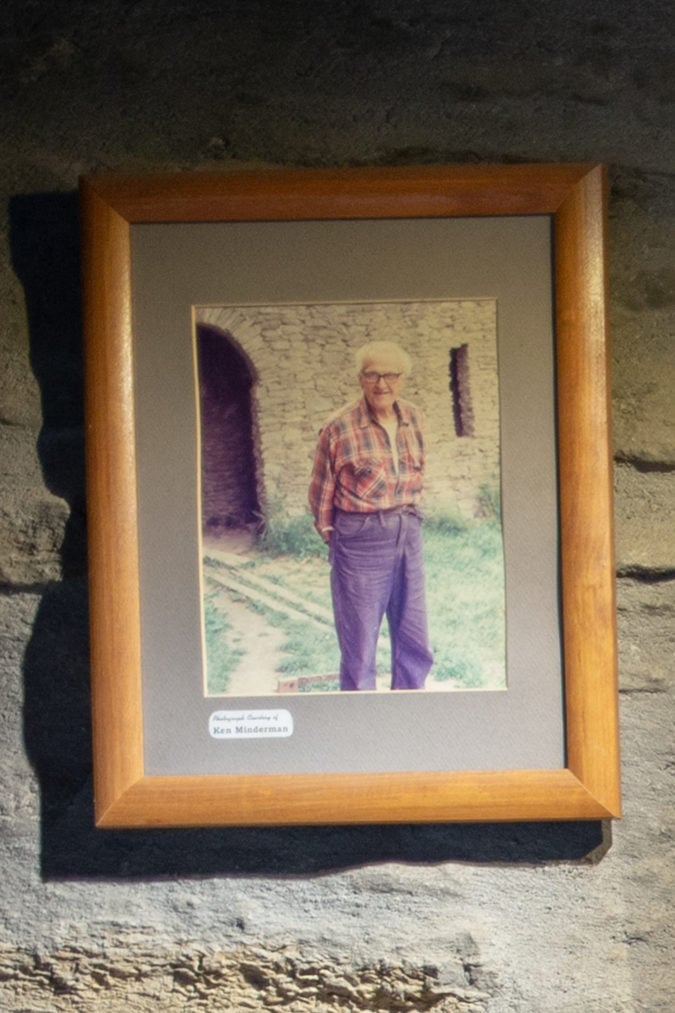

In addition to being a medic, “Andrews was a Sunday school teacher, preacher, professor, author, poet, publicist, notary public, typesetter, proofreader, and editor,” Russell says. “He could write, read, and speak seven languages fluently and held several different degrees.” But Andrews’ enduring claim to fame is the castle that he built and worked on nearly every day for 52 years—from 1929 until 1981, when he died (for real this time) at the age of 91.

Andrews’ medieval masterpiece, Historic Loveland Castle and Museum (also known as Château Laroche, French for “rock castle”), is located on the banks of the Little Miami River about 25 miles northeast of Cincinnati, Ohio. In the 1920s, The Cincinnati Enquirer offered plots of land along the river to anyone who paid in advance for a year subscription; Andrews acquired 11 lots and erected his castle from native river stone and concrete bricks molded in milk cartons. When Andrews died, he left his life’s work to the Knights of the Golden Trail, whose members still maintain the castle.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

Triple door and trick stairs

On a gray and damp late winter Saturday, I’m one of only a handful of visitors to Loveland Castle. Signs guide me down a steep, winding road with several hairpin turns; it turns out that the narrow road was also built by Andrews and still can’t accommodate buses.

As the walled castle comes into view, I’m tempted to say that it looks out of place—southern Ohio isn’t known for its medieval architecture—but the imposing structure somehow fits right in. Isolated from the surrounding residential neighborhood, the castle is set into the heavily wooded, sloping riverbank. If I ignore the portable toilets and modern cars in the parking lot, it’s surprisingly easy to slip out of time.

As my eyes adjust to the castle’s dark interior, I spot Russell behind the counter. Somewhat surprisingly, he’s not wearing a suit of armor, but jeans and a sweatshirt. He welcomes me to the castle “built by hand by one man,” and explains that Andrews was “one of the world’s authorities on medieval architecture and castles.” Andrews studied in New York at Colgate University and in France at Toulouse University; he modeled his second floor ballroom after one in France’s Château de la Roche. A German game room on the first floor includes chess, checkers, and several puzzles.

Loveland Castle has everything you’d expect from a working fortress, including a dungeon, dry moat, bell tower, and English battle deck. A second-floor balcony provides a nice view of the terraced gardens, where Andrews grew fruits and vegetables year round in hotbeds—heated by railroad lanterns—of his own design. Narrow windows ensure that knights under attack would be able to shoot arrows outward, while making it difficult for incoming strikes to hit their intended targets.

The front door is three layers thick, made of 238 pieces of wood puzzled together with 2,530 nails. It’s actually three doors in one—the top half opens separately, and the bottom half contains a wicket gate, a smaller door used as another line of defense. “If you’re a full-sized adult you have to bend down and come in head first,” Russell says. “If you’ve got a weapon in your hand you’ve got to extend your weapon which deems it useless.”

One set of trick stairs leads to the second floor and another down into the dungeon. The narrow, winding stairs are “made to make you feel uncomfortable and are really easy for one person to defend,” Russell says. “You can’t shoot an arrow or sword fight in them and the step heights are all different. It makes you look at your feet. Even though you were born with them at the end of your legs, you’ll lose your feet if you don’t pay attention to them on these stairs.”

Knights of the Golden Trail

Authorities took their time informing Andrews’ family and friends that he wasn’t, as they had previously thought, dead. So long, in fact, that Andrews’ fiance had already married another man. After this, according to the KGOT, Andrews “veered away from women, period,” and despite fielding more than “50 marriage proposals later in life, he turned all of them down.”

Andrews, who retired from Cincinnati’s Standard Publishing Company, met regularly with a group of local boys for Sunday school and Boy Scout activities. The group called themselves the Knights of the Golden Trail. When they wore out two old army tents Andrews told them, “If you gather me stones, I’ll build you two rock tents.” When the tents began to resemble towers, Andrews decided that his group of “knights” deserved a proper castle.

Nearly a century after its founding, more than 300 people have been knighted and today there are still around 50 active KGOT members. The “golden trail” refers to the Ten Commandments, but Russell says, “Anybody can come out and join our organization—you just have to come out and work around the castle.” Pages and squires become knights when they’re old enough, and potential members need to be sponsored by an existing member or raised up into the knighthood by a family member. “Harry wanted us to continue working on the castle, that’s why he taught us how to work on the castle,” Russell says. “Family isn’t just blood.”

KGOT members are stewards not only of the castle—the organization’s world headquarters—but the surrounding land and waterways. According to their website, “The Knights refuse to be part of pollution happening in the Little Miami River. They have been green for a long time before it was ‘cool’ to be green.”

A hobby

Andrews, the subject of the 1979 PBS documentary Castle Man, was by all accounts a selfless, hardworking, and humble man. At one time he was the oldest living notary public in the state of Ohio, never charging more than a quarter for his services. He allegedly had an IQ of 189 (“genius” begins at 160), published a book on immigration for the U.S. government, and offered his castle to the production companies of a Robin Hood movie and four Frankenstein films for free. When asked by the Enquirer if he built the castle as a monument to himself, Andrews replied, “No, it’s only an avocation [a hobby]. I’ll not be buried beneath it.”

In March of 1981, Andrews was trying to put out a trash fire he had started on the castle grounds when he was severely burned. He died of his injuries a few days later and his body was cremated. A year before his death he told the Enquirer that he “estimated he had six or seven years’ work on the castle wing,” and he had plans to add an apartment, showroom, and chapel. Today, the castle is available to rent for small weddings, Boy Scout sleepovers, school tours, and paranormal investigations.

Castle Man, which plays on a loop in one of the castle’s outdoor niches, shows Andrews hard at work molding bricks from milk cartons—he made nearly 33,000 over the years. He initially worked from plans, but when they went missing he continued building from memory. “[Medieval] knights did it—I don’t know why modern knights can’t,” Andrews said. “Sometimes I don’t feel like it, but I work just the same.”

If you go

Historic Loveland Castle and Museum is open daily between April 1 and September 30, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Between October 1 and March 31 it’s open on Saturdays and Sundays, weather permitting. For more information on Ohio’s castles, visit Ohio.org.