During a road trip from New Orleans to Miami Beach, I expected to come across seafront casinos and neon-lit barbecue joints. What I didn’t expect was the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art (OOMA).

Located along the Gulf Coast in Biloxi, Mississippi, the museum cuts a striking presence. The building is made of curving, twisting brick, and a large silver pod peeks out like a spaceship from a huddle of ancient oaks. It’s as if the trees have sprung up around the buildings and not the other way around. Designed by Guggenheim Museum Bilbao architect Frank Gehry, the museum pays tribute to local artist George Ohr. Known as “The Mad Potter of Biloxi,” Ohr helped spearhead the abstract expressionism movement—but not until after his death in 1918.

A duck amongst the chickens

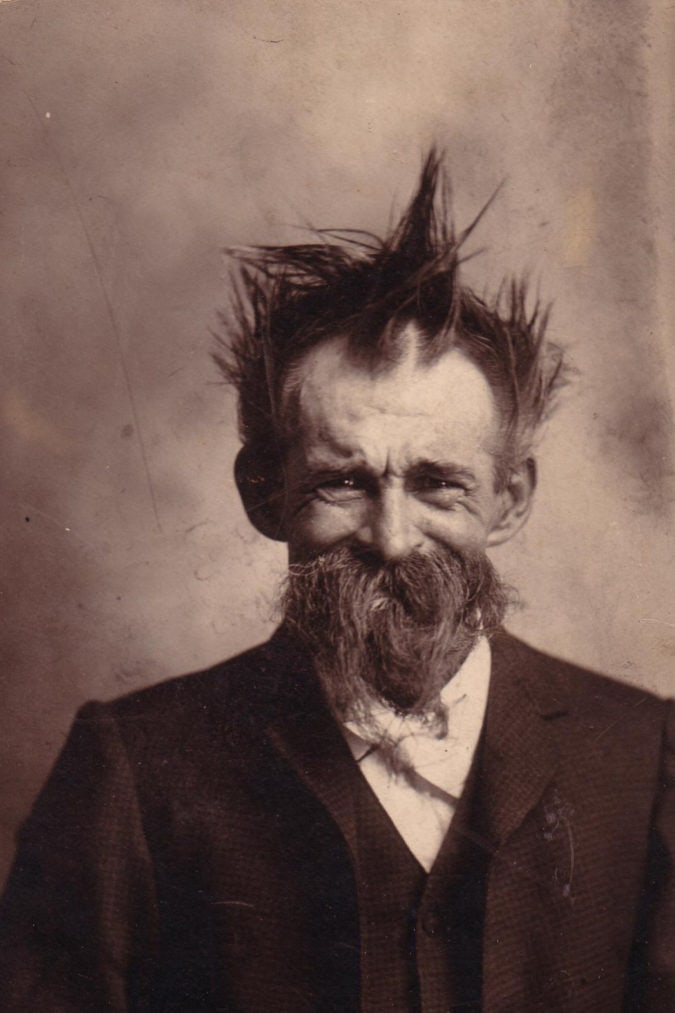

The more I find out about Ohr, the more I’m intrigued. He left behind a self-published autobiography and many writings about his life, which paint the picture of an eccentric man who was undeniably brilliant. He lived his life always feeling like the odd one out, describing himself as “a duck amongst the chickens,” never sure where he belonged. But at some point, Ohr began embracing his perceived differences and cultivating his cheeky sense for the bizarre into art.

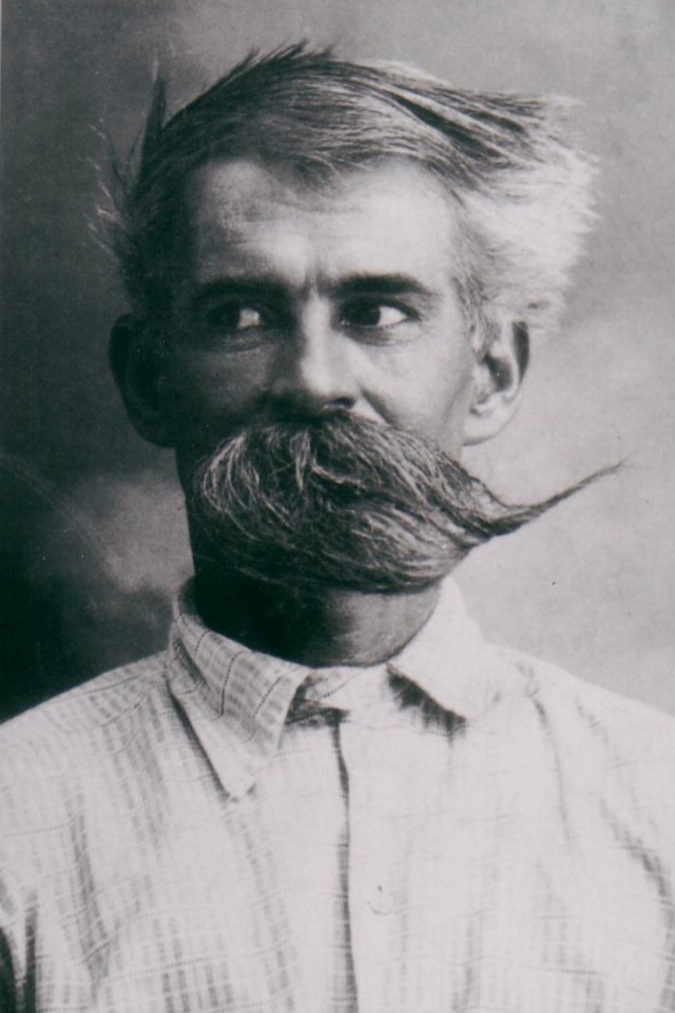

He certainly looked the part: For much of his life, Ohr wore a grand mustache so long, he could tie it behind him. Born in Biloxi in 1857, Ohr found his calling in 1879. He left his job as a laborer to work for family friend Joseph Fortune Meyer, a potter in New Orleans. Ohr worked with Meyer for two years, making $10 a month and learning the skill of the potter’s wheel.

“After knowing how to boss a little piece of clay into a gallon jug, I pulled out of New Orleans and took a zigzag trip for two years,” Ohr wrote in a two-page autobiography in 1901. “I sized up every potter and pottery in 16 states, and never missed a show window, illustration, or literary dab on ceramics since that time.” He learned it all—how to dig and process his own clay, as well as throwing, glazing, and decorating, and dreamed of opening his own studio. Ohr saved what he could, and put his laboring and blacksmithing skills to good work on the side. Once he had his own wheel, it was as if he had finally found his place in the world: “I felt it all over, like a wild duck in water,” he wrote.

Deliberately twisted

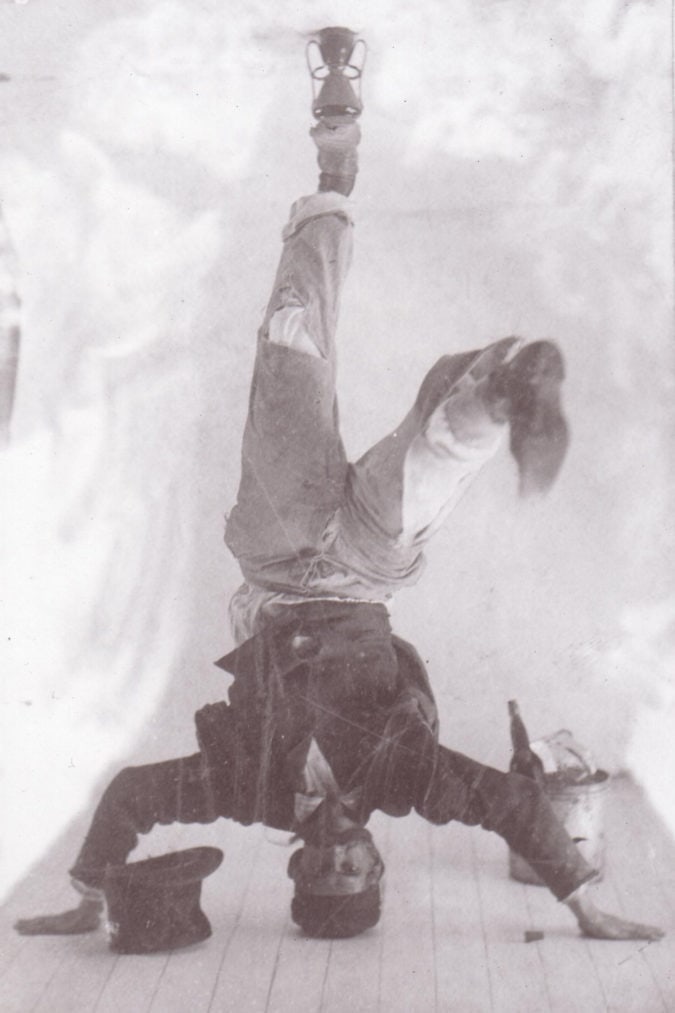

Ohr mastered the typical pots, bowls, and pipes of the time, earning enough of a living to feed his family. He played with the functionality of each item, taking a traditional shape and adding his own little twists and oddities. Things changed in 1894, when a fire blazed along the Biloxi coast, destroying Ohr’s entire workshop. He mourned the loss greatly, and decided to change course. He built a bigger studio and started creating “art pottery,” no longer purely functional, but also expressive. Today, it’s clear that Ohr’s style was unquestionably unique: Smithsonian Magazine once described his pots as having “rims that had been crumpled like the edges of a burlap bag,” his pitchers as “deliberately twisted,” and his vases as “warped as if melted in the kiln.”

The Ohr-O’Keefe Museum’s most popular pieces are Ohr’s Puzzle Cups: hefty looking cups, like a typical coffee mug, but with a bit of trickery built in. “The puzzle mugs have holes just below the rim that make the traditional method of drinking from them impossible,” explains Nathen Lytle, OOMA’s director of marketing. “Ohr’s challenge to visitors was to figure out how to drink out of them without spilling. He hid holes—three along the rim and a hidden one beneath the top curve of the handle—that the visitor would have to find and cover to gain suction to the bottom.”

All of Ohr’s works are displayed unlabeled, as the artist felt labels were distracting. Instead, the museum provides a printed guide with more information about each item. This way, visitors can focus solely on the shapes and bold colors. In the museum, an attendant demonstrates how shining a light directly onto the works makes them come alive, revealing glimpses of colors that change and shift: deep blues, vibrant greens, vivid fuchsias, and lively yellows.

Ohr was always sure of his own talent; a sign outside of his studio proclaimed: “Unequaled unrivaled—undisputed— GREATEST ARTPOTTER ON THE EARTH.” Another sign read: “Get a Biloxi Souvenir, Before the Potter Dies, or Gets a Reputation.” He remained convinced his pieces were “worth their weight in gold,” and his asking price was typically between $10 and $50 per piece ($300-$1,500 in today’s money), which was almost always met with skepticism and scorn.

Ohr stopped making pottery in 1908 and died 10 years later, and it would be several decades before his work saw the light of day again. “I have a notion that I am a mistake,” he wrote, but added, “When I am gone, my work will be praised, honored, and cherished. It will come.”

A kindred spirit

In the late 1960s, antiques dealer James Carpenter came across a massive collection of ceramics in the back of the Ohr family’s auto shop, where they’d been stored away in crates. He bought the lot, and the pots and vases made their way to museums such as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

When renowned artists such as Andy Warhol began collecting some of Ohr’s pots, and Jasper Johns featured them in his paintings, the potter’s acclaim soared—and with it, the value of his work. By the 1980s, the same pots that had been scoffed at were selling for tens of thousands of dollars. It appeared that, more than 60 years after his death, Ohr’s time in the spotlight had finally come.

“I think his work was ‘discovered’ at the right moment,” says OOMA curator Douglas Myatt. “The art world was able to recognize a kindred spirit in Ohr. He might have been around decades before them, but I think he would have understood and appreciated the work of ‘modern’ artists like Rothko, Johns, Calder, and even Bourgeois.”

Ohr’s influence was finally given a permanent home with the construction of the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, a Smithsonian Affiliate. It was the first museum in the U.S. to be dedicated to a single potter. The current museum complex, which opened in 2010, showcases additional exhibitions by other artists from along the Gulf Coast and around the world. There are seven buildings in all, including a light and airy welcome center, which displays Mississippi crafts, and a center for ceramics, where visitors can join clay-making classes. Of the five buildings designed by Gehry, it is the striking silver pods—connected by a glass atrium—that houses the collection of Ohr’s life’s work.

OOMA is a remarkable celebration of an artist who never felt fully appreciated in his own lifetime. “Eventually,” Ohr wrote, “the nation will build a temple to my genius.” And that’s exactly what they did.

If you go

OOMA is currently open with limited hours: Thursdays from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., and Fridays and Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.