My first sight of the museum is a showstopper: A huge dinosaur is attacking its facade, wearing—due to COVID-19—a face mask. But inside the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, the world’s biggest (and often named best) museum for children, is an attention-grabbing exhibit with an even more lasting impact: a display devoted to four children who changed the world.

The newest honoree, Malala Yousafzai, was just a teenager in 2012 when she was shot in the head by the Taliban due to her outspoken support of education for girls in Pakistan. The Malala-focused exhibit, which opened on September 18, joins others about Anne Frank; Ruby Bridges, one of the first Black children to integrate New Orleans public schools; and Ryan White, the Indiana teenager who battled prejudice after contracting AIDS from a blood transfusion. The museum had no idea how timely its decision to feature Malala would be: After a 20-year absence, the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan in August.

“We wanted to make the Power of Children exhibit relevant to what’s happening in the world today,” says Kimberly Harms Robinson, director of public relations at the museum. “Frank lived in the 1940s, Bridges in the 1960s, and White in the 1980s. So we created a committee to nominate a child of the 2000s, and Malala was the overwhelming choice.”

12 years of education

The Indiana museum is renowned for other well-researched exhibits such as Treasures of the Earth, displaying re-creations of an Egyptian pharaoh’s tomb, China’s Terra Cotta Warriors, and Captain Kidd’s Caribbean shipwreck. To create Malala’s exhibit, the museum worked closely with her family in England—especially her father, Ziauddin Yousafzai—and their nonprofit, the Malala Fund, which supports 12 years of education for all children globally.

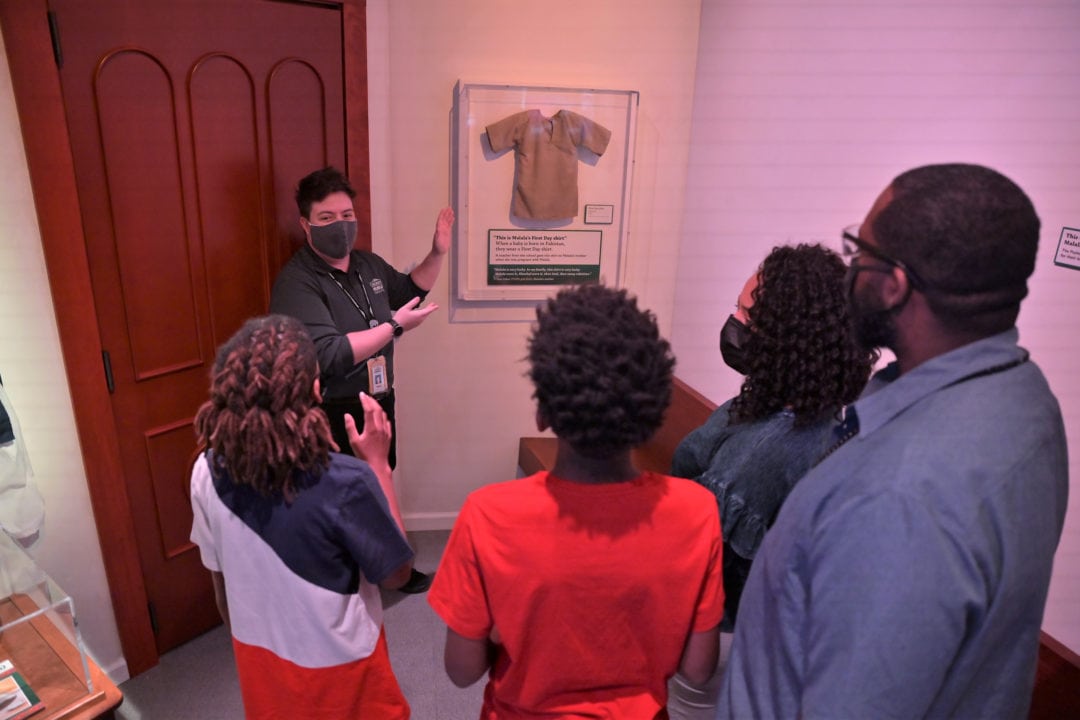

Designed to resemble her family’s two homes in Pakistan, a whitewashed stucco and brick house with a walled brick courtyard displays original objects (on loan from the family) and a recreation of a typical Pashtun household. Carpets and furnishings are modeled after those owned by the family, who fled Pakistan after the 15-year-old was shot on a bus, leaving most of their possessions behind. A vibrantly-colored, embroidered, 2-foot-long tapestry in geometric designs on display once hung in their home.

A replica of Malala’s prized school uniform hangs on a hook. The school she attended was founded by her father, a teacher who resolved that his daughter would be educated and have her own identity. There’s a replica of the wooden desk and computer where 11-year-old Malala wrote a blog about life under the Taliban, who banned education for girls, TV, and music, and publicly executed their foes.

Malala spoke to the journalist that helped publish her blog, “Diary of a Pakistani Schoolgirl,” on the BBC’s Urdu-language website on a Nokia cellphone, and there’s a similar phone on display, donated by her family. The many trophies and medals Malala and her two brothers won for their academic achievements and speeches are here too. A video shows how much Malala and her friends valued knowledge: Instead of traditional henna patterns, they adorned their hands with calculus and chemistry designs.

I’m moved by the family tree, where her father lovingly inscribed Malala’s name—the first woman’s name to be added to the Yousafzai family tree in 300 years (it’s in the lower right hand corner). The exhibit includes a copy of her Nobel Peace Prize diploma from 2014 (at age 17, she was the youngest-ever winner), which she autographed and donated. Original letters and cards sent to Malala in a hospital in England, where she took months to recover after being critically wounded, from supporters worldwide are on display here as well.

‘The story of many girls’

Malala’s exhibit describes the challenges she and other girls in Pakistan faced trying to further their education. After the Taliban conquered her region in 2007, and forbade girls to attend school, she hid her schoolbooks beneath her shawl and went to school in fear. The year she was shot, she led a group of children’s rights activists who gave presentations to politicians in Pakistan.

“One child, one teacher, one book, one pen can change the world,” writes Malala in her 2013 autobiography, I Am Malala, praising the transcendent power of education in fighting ignorance, extremism, and violence. “I tell my story not because it is unique, but because it is the story of many girls.” Fittingly, the exhibit also shares the stories of 10 other girls—from all over the world—who championed their right to learn in touch-screen videos.

Brave and wise beyond her years, Malala was strongly influenced by her father’s progressive views. “If people come here and see this exhibit, they see how one family, with great values of equality, justice, love, respect, and empathy, can change their communities and their countries as well,” Ziauddin Yousafzai told the museum.

He grew up with five sisters and noticed that he and his brother were served better food and had better clothes and more shoes, simply because of their sex. “My sisters’ views and opinions did not matter, but the worst discrimination was their deprivation from education,” he says. “I tell people education changed me. I believe in the identity of every girl and woman. I also personally believe that education gives us values.”

If you go

The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis is open every day except Monday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the fall and winter, and 7 days a week in the spring and summer. Admission on the first Thursday of the month from 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. is $6.