Mark Cline has been shot out of a canon, hanged, and had his head cut off. He has ridden blindfolded through a ring of fire on a unicycle. His hands were bound behind his back and he was submerged in a milk can full of water, from which he easily escaped—twice. But like one of his heroes, Harry Houdini, Cline doesn’t consider himself a magician.

Since he was 19 years old, Cline has been creating fiberglass figures. His Enchanted Castle Studios creations populate roadside attractions throughout the country. He has built two full-size replicas of Stonehenge and recently opened Dinosaur Kingdom II, which, like Cline himself, is too difficult to describe in just a few words. For more than 20 years, he has hosted “Haunting Tales,” a nightly ghost tour in Lexington, Virginia—but he doesn’t consider himself to be a tour guide either.

A documentary filmmaker dubbed Cline the “Blue Ridge Barnum,” which is close, but still not entirely accurate. P.T. Barnum was a showman, yes, but he was also a liar. Cline is careful to make a distinction between the art of deflection and deception. He may be very good at conjuring up an illusion on the spot, but nothing about Cline feels disingenuous.

Instead of producing rabbits from top hats, Cline feels drawn to the characters underneath them—Uncle Sam, Willy Wonka, and the Wizard of Oz—and often portrays them in local parades. But underneath the costumes and behind the props, Cline is unapologetically and uniquely himself. When pressed to choose just one title, Cline simply says, “I’m an entertainer.”

The Wizard of Natural Bridge

I arrive at Cline’s Enchanted Castle Studios in Natural Bridge, Virginia, on a bright, sunny summer day. He is expecting me and before I even sit down he launches into his origin story. I get the sense that he’s done this before, and he later tells me he does “one or two interviews a week.” Even though his speech feels rehearsed, I can’t help but be charmed by his enthusiasm and seemingly boundless energy.

The yard of Enchanted Castle Studios. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Cline’s workshop. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A wall of paint in Cline’s workshop. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Head molds from a defunct wax museum. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Cline’s collection of dolls. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A marker from Foamhenge. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Fiberglass molds at Enchanted Castle Studios. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A praying mantis. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Huge fiberglass hands. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

He leans back in his chair, puts his feet on his desk and says it all began when he was 11 or 12 years old. His father took him to Dinosaur Land in White Post, Virginia, and Cline was enamored with the park’s fiberglass figures created by Jim Sidwell. “I told my dad, ‘One day I’m going to build dinosaurs like that,’” Cline says, and he kept his word. Almost 50 years later, Dinosaur Land is still around and now features several of Cline’s creations alongside Sidwell’s originals.

While Cline’s creativity was evident from an early age, he struggled academically. He was placed in a class for children with learning difficulties and spent most of his life feeling insecure about his own intelligence. His fourth grade teacher taught Cline the art of papier-mâché and decades later, she told him that he hadn’t been separated from his peers because of his lack of intelligence, but rather because of his abundance of creativity. It was a breakthrough.

“I realized that people can go through life believing things that simply aren’t true,” Cline says. “For 43 years I thought I was stupid. I was the scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz. But it turns out nothing can stop you but you.”

While Cline may have spent most of his life wishing for a brain, the man I meet feels much more like the Wizard than the clueless sidekick. Enchanted Castle Studios is not officially open to the public, but Cline doesn’t necessarily turn away visitors who pull through the gate flanked by red, white, and blue turrets. “I ask them if they have the witch’s broomstick,” Cline says. “Not many have it, but I let them in anyway.”

As we’re touring his workshop, Cline grabs a miniature version of the Wizard of Oz and strikes a pose in front of a fiberglass hot air balloon. The Oz figures, including a miniature Emerald City, the Witch’s Castle, and a flying monkey, are destined for a playground in Maryland’s Watkins Regional Park. “I tried to make the monkey look a little happier,” Cline says.

Cline tries to spread happiness wherever he goes. He does a lot of charity work, headlining parades and benefit shows, and he believes that sometimes laughter really is the best medicine. “Compassion is what measures us as humans,” Cline says. “Helping others, using your abilities and talents to inspire others. I try to bring joy, which brings healing. Anybody can be a healer.”

Of molds and Muffler Men

I don’t have to liquidate a witch to gain entry into Cline’s inner sanctum, but I have done my research. Fans of classic roadside attractions will recognize Cline’s work, whether or not they pay attention to the man behind the curtain; he has pieces at campsites, miniature golf courses, shops, theme parks, and in private collections all over the world. When I visit, he’s in the process of refurbishing three Muffler Men that used to stand at the Magic Forest in Lake George, New York.

Cline repairs and restores vintage figures and creates new pieces from his extensive collection of molds. He can make almost anything, including lions, tigers, bears, dragons, gorillas, vikings, castles, camels, and giraffes. Cline points to a large skull lying face-up in the yard: “I made one of those for [musician] Alice Cooper,” he says. One of his most recent creations, a space cowboy Muffler Man named Buck Atom, stands outside of a new gift shop on Route 66 in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

When I first arrive, I think I spot Cline working in his shop but it’s just the head and torso of a figure destined for Dinosaur Kingdom II. He has enough body parts scattered around to assemble a small army; three Muffler Men heads, various arms and legs, and a wall of unfinished heads from a now-defunct wax museum. Fittingly, Cline says that his fiberglass career began when he learned how to make a cast of his own hand.

Cline was “essentially homeless,” when he sat on a park bench to write in his journal and asked himself, “What do I want to do with my life?” He decided that above all else, he wanted to be happy. “But what’s going to bring me this elusive happiness?” he wondered, before coming to the realization that “helping others is the key to personal happiness.”

Cline hitchhiked back into town and went to the local employment office. He took the only job they had—mixing resins for fiberglass fabrication—and the rest is, as they say, history. “I was in the right place at the right time,” he says. “What if I wasn’t in the park that day or what if that woman hadn’t picked me up? Just a fraction of a second would’ve changed everything. Mark Twain once said, ‘I was seldom able to see an opportunity until it had ceased to be one.’”

Optical illusions

With such an impressive resume and packed schedule, it would appear that Cline rarely passes on an opportunity. It’s still early, but Cline ran three miles before I arrived. He always wanted to be a cartoonist, and now in his “spare time,” he draws comics. A newspaper clipping featuring a photo of young Cline drawing says, “The youngster, with his active mind and big imagination, rarely has ‘nothing to do.’ If he’s not with a school group building a psychedelic bird house or with the gang out back building a split-level tree house, then he’s inside working on his comic strip cartoon characters.”

Cline with the soldier he modeled using his own head. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan An unfinished viking. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A clown Muffler Man head. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A dragon stands near the entrance. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Camels. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan These Muffler Men once stood at the Magic Forest in Lake George, New York. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A giraffe head. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A large skull. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A Mickey Mouse figure. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Cline is clearly proud of his comics and he has reason to be—in addition to being a talented visual artist, Cline is a master storyteller. He’s currently working on a new 100-page book called Funnies from the Morgue, comprising 11 different stories each with a twist ending. He describes “Down the Drain,” which features a plumber who falls in love with a turd, as a “Shakespearean love story—very Romeo and Juliet-esque, very tragic.”

Three nights a week in the summer (and weekends in October), Cline dons another top hat for his ghost tour, which promises “humor, mystery, illusions, history, and fun.” An accompanying book illustrated by Cline contains dozens of spooky, intricately inked scenes which incorporate complex optical illusions. “It doesn’t matter if there are a hundred people on the tour or two,” Cline says. “Everyone gets the best tour I can give them. Because the number doesn’t matter—the matter doesn’t number.”

During my visit, Cline says several things that could easily be followed by Willy Wonka’s catchphrase, “Strike that, reverse it.” As he leads me through his fiberglass factory, Cline produces a door where just seconds before, there was none. “Here at the Enchanted Castle, when the door is too small to take things through, we just open the wall,” he says. Behind it sits a parade-ready Wonka-themed float topped with larger-than-life ice cream cones, squirrels, and nuts. Cline prefers Gene Wilder’s Wonka to Johnny Depp’s, but he’s like a combination of both—without the sadistic streak.

“Small moments can mean something major to a child,” Cline says. “Anything that a child asks an adult is not unimportant to them—they deserve an answer.”

Foamhenge and Dinosaur Kingdom II

Cline loves April Fools’ Day, and one of his most famous creations, Foamhenge, was originally erected in Natural Bridge on the night of March 31, 2004. The Stonehenge replica made from foam blocks was an instant success and was featured on NCIS and Jeopardy. But when the area was designated a state park, Cline was forced to find a new home for Foamhenge. It now resides an hour west of Washington, D.C. at Cox Farms, but Cline laments the move. “It’s not as magical there as it was on the hill surrounded by mountains,” he says. In 2012, Cline was commissioned by a billionaire to build a second Stonehenge, called Bamahenge, which is currently on display in Alabama.

Cline’s life may seem charmed, but he’s no stranger to sorrow. In 2001, a fire burned down one of his storage buildings, and in 2012, another fire destroyed his monster museum and first dinosaur park. In 2016, he opened Dinosaur Kingdom II, which is probably as close as one can get to touring the inside of Cline’s brain. I’m lucky enough to get a tour from Cline himself, and he’s clearly in his element.

“Welcome back to 1864,” Cline says as we enter the park through the “extinction junction” train depot. The Old West-inspired town was once part of a motel and Cline turned each building into its own interactive funhouse. At the undertaker’s, dinosaurs crawl in and out of a casket; at the dentist, guests can try their steady hand at a game of “Dinosaur Operation,” removing metal pieces such as the “peanut brain” or “tailbone.”

An elaborate introductory video explains the park’s concept—the “untold” story of how Union soldiers used “dinosaurs as weapons of mass destruction” against the South during the Civil War—which, after I’ve spent a few hours down the rabbit hole with Cline, somehow doesn’t seem all that crazy. “This was nothing but a forest,” Cline says. “I had to come in here and create an adventure. Very few roadside attractions like this exist anymore. I brought back something that almost really did become extinct.”

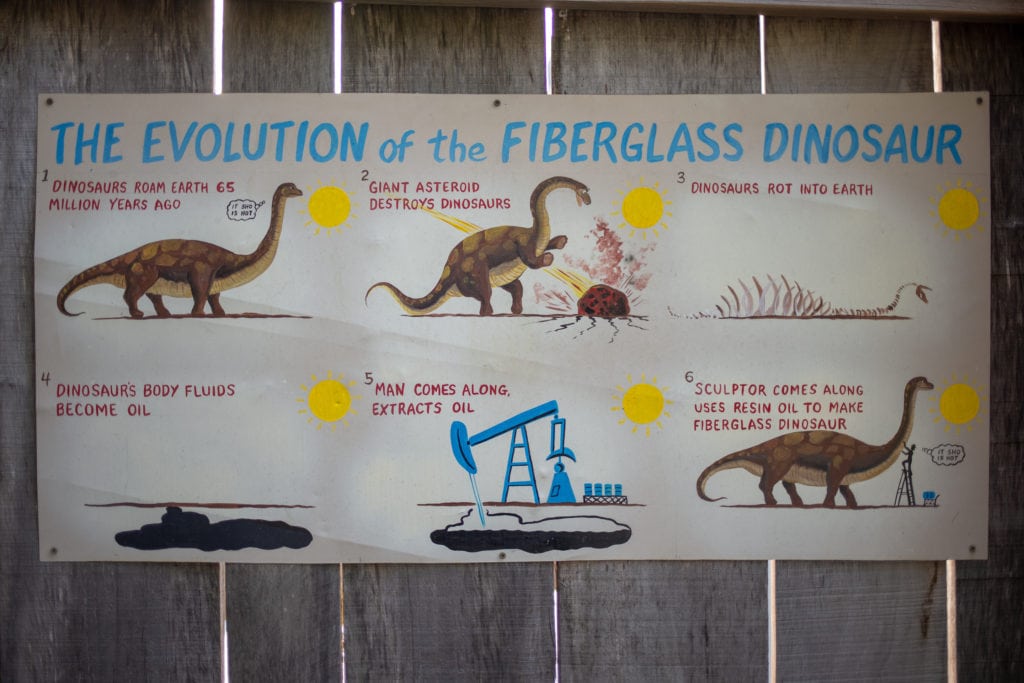

The undertaker’s. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A Union soldier and a Triceratops. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Dinosaur Operation. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Trying to make an escape. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan “Xtreem danger!” | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Milking a Stegosaurus. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Stonewall Jackson and his steampunk arm. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan One of Cline’s slime figures. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The evolution of a fiberglass dinosaur. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Guests enter the park through the Extinction Junction train station. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Like Dinosaur Land, the main attraction here is the dinosaurs, set up in various scenes that together tell a larger story. There are no explanatory plaques, but visitors savvy enough to scan a QR code will be rewarded with videos of Cline acting out select scenes. The wooded path is full of strange displays that could have only been dreamed up by Cline: A steampunk Stonewall Jackson fights a Spinosaurus, a Mennonite boy milks a Stegosaurus, and a huge ape steals a pair of jeans from a caveman. At least one of the soldiers was made from a mold of Cline’s own head.

“Nobody else is doing it the way I’m doing it,” Cline says. “You create the story, you create the adventure, you become the hero of your own story. That’s what life’s all about.”

If you go

Foamhenge at Cox Farms is open 12 p.m. to 2 p.m. on Saturdays from April to August and select dates from September to December. Dinosaur Kingdom II is open on weekends from spring to fall.