In 1854, John McSorley, an Irish immigrant to New York City from the County Tyrone, opened an ale house on East 7th Street. Originally called The Old House at Home, McSorley’s Old Ale House briefly tried selling hard liquor in the early 1900s. Today, though, it only serves two types of beer: a light ale and a dark ale.

In a city filled with pricey craft cocktails and thousands of beers on tap, McSorley’s lack of choice—and the $5.50-per-drink price tag—is as refreshing as their light ale, which comes in pairs. John kept horses out back and his son, Bill, who eventually took over the bar from his father, was an avid reader. The two-glass policy evolved so father and son could tend to their hobbies in between pours.

McSorley’s is not the oldest bar in New York City—that distinction goes to Fraunces Tavern, open since 1762—although Shane Buggy, a bartender at McSorley’s, disputes this fact. Fraunces Tavern has been rebuilt several times, but McSorley’s has remained virtually unchanged—and has served ale continuously, even during Prohibition—for 165 years.

At the very least, McSorley’s can claim the title of “oldest Irish pub” in the city. It’s no surprise that McSorley’s—with its green, shamrock-emblazoned storefront—is a popular destination on St. Patrick’s Day. Normally open daily at 11 a.m., doors will open at 8 a.m. on Sunday, March 17, to accommodate the morning crowds.

But on a Tuesday afternoon, it’s easy enough to grab a couple of beers, settle into a worn wooden table, and imagine the people who have passed through its double doors in need of “a cold beer to warm up”—a phrase Buggy uses frequently.

Raw onions and no ladies

President Abraham Lincoln visited McSorley’s in 1860 after his famous speech at the nearby Cooper Union; the bar has a framed newspaper announcing his death in addition to a wanted poster seeking the capture of his assassin, John Wilkes Booth. Peter Cooper was a friend of John McSorley’s and a regular. When he died in 1883, his chair was retired and still sits behind the bar.

E. E. Cummings wrote a (somewhat unflattering) poem about his time spent at the pub, which begins: “i was sitting in mcsorley’s. outside it was New York and beautifully snowing. Inside snug and evil.”

It’s also easy to imagine who hasn’t visited McSorley’s over the years. It wasn’t until 1970 that women were finally allowed inside. The pub, whose motto was “Good Ale, Raw Onions, and No Ladies,” was not yet ready to get with the times. In fact, they fought hard to keep women out of the establishment and even considered becoming a private club to do so.

In 1939, when then-owner Daniel O’Connell died and left the bar to his daughter, Dorothy O’Connell Kirwan, she honored the no-women policy and appointed her husband as manager. When the bar celebrated its centennial, Kirwan had her celebratory drink outside on the sidewalk. After women were finally admitted, Kirwan declined to be the first woman served, a decision that makes more sense if you know that the first women’s restroom wasn’t added until 16 years later.

Spending eternity at McSorley’s

McSorley’s has all the hallmarks of a classic tourist attraction, but Buggy says it’s the regulars who really make the place special. Eleven years in, Buggy still refers to himself as “the new guy.” One bartender has been working at McSorley’s for 47 years (and counting), and several customers have been coming in on a regular basis since the 1950s. “Not a day goes by without someone coming in and starting a conversation with, ‘The last time I was in here…’” Buggy says.

For some regulars, McSorley’s is literally their last stop. The ashes of seven different people are interred in various vessels—including a flask—behind the bar. If you’re a close friend of one of the seven, you can request that their vessel be brought out so you can continue to drink together.

Spending eternity at McSorley’s isn’t an option available to everyone. “We won’t take just anyone,” Buggy says. Because of this exclusivity, patrons have been known to surreptitiously sprinkle a loved one’s ashes on the floor. A thin layer of sawdust—a relic from another era when patrons would track in mud and horse manure—makes it plausible that a bit of grandpa’s ashes could be added on the sly.

In addition to hosting memorials for dearly departed regulars, McSorley’s has its fair share of happy gatherings too. Couples have met and been married at McSorley’s, graduates of nearby schools host reunions, and, once a year, hundreds of regulars gather for an outing to New Jersey.

The bar regularly hosts war veterans, and some have left memorabilia behind. Patrons have gifted the bar two purple hearts, challenge coins, patches, and helmets from all eras. There’s a Civil War-era bayonet, shackles from Camp Sumter, an invitation to the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, and an original print of Nat Fien’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph “The Babe Bows Out,” donated by Fien, a McSorley’s regular.

Infamous artifacts

Unlike the drinks, which are slammed on the bar seconds after ordering, change arrives slowly at McSorley’s. In 1994, Teresa Maher de la Haba, daughter of current owner Matthew Maher, became the first woman to tend the battered wooden bar. The décor hasn’t changed much in the past 165 years—pieces are rarely added or removed and everything is perpetually dusty.

When Harry Houdini visited in the early 1900s, he was issued a challenge by O’Connell, then a regular patron, former policeman, and eventual McSorley’s owner: “You can get out of your own handcuffs, but how about you try escaping from mine?” Houdini accepted and did escape, leaving both sets of cuffs behind. Houdini’s set is hanging from the ceiling, while O’Connell’s remains cuffed to the bar.

Perhaps the most famous artifacts are the wishbones dangling from a gas lamp above the bar. After finishing a free meal at the bar, soldiers departing to serve in WWI left their wishbones—from turkeys, chickens, and one duck—intending to collect them upon their safe return. In 2011, a city health inspector insisted that the wishbones, encased in years of dust, be cleaned.

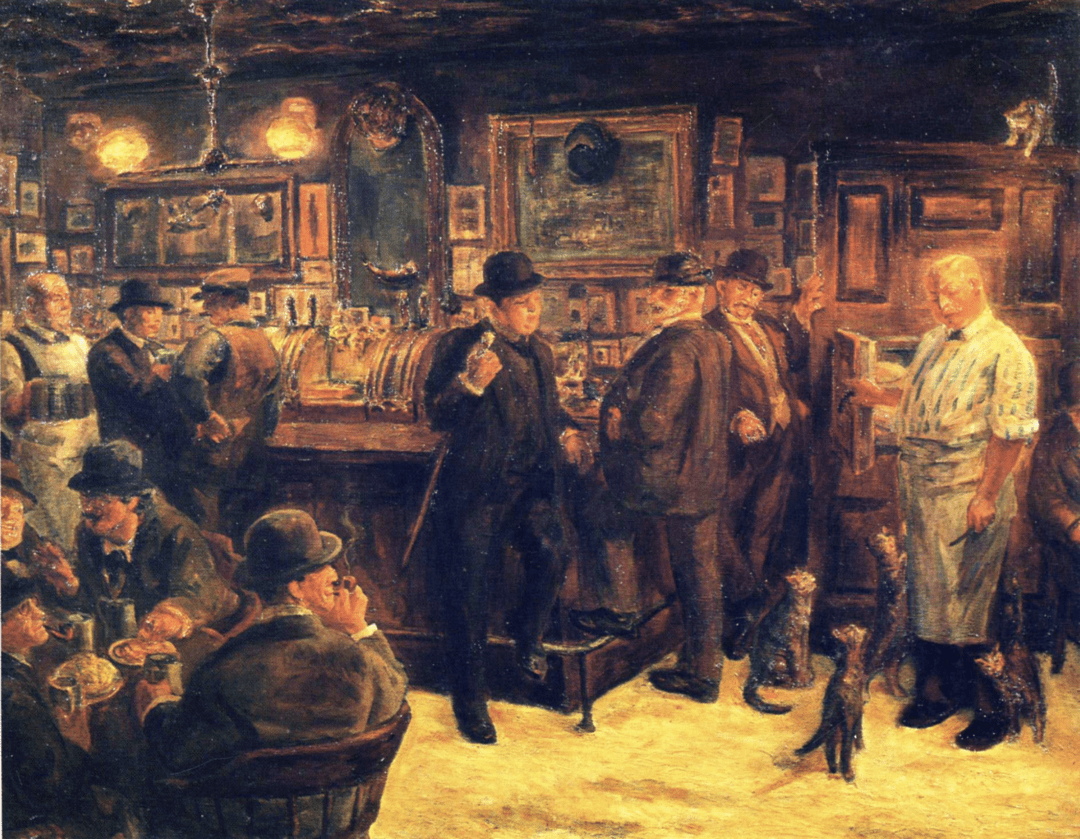

Health inspectors also had a problem with another McSorley’s regular—Minnie the Second, one of many cats who have called the pub home over the years. John McSorley loved cats, keeping up to 18 in the bar at once—a quirk immortalized by John French Sloan in his 1929 painting McSorley’s Cats. In 2011, New York City passed a law forbidding bars and restaurants from keeping cats. Minnie was forced out and, five years later, the Department of Health closed McSorley’s for four days while they resolved a rodent problem.

Once again, a story can be told by what you won’t find at McSorley’s. There are no bar stools and all seating is communal. The only other drink available, in addition to the two ales, is soda, and a limited, reasonably-priced food menu is posted daily on two chalkboards. There are no TVs at McSorley’s and no ambient music—the only noises you’ll hear are the clinking of glasses and the muted hum of people’s conversations.

“At a sports bar, your eyes are glued to the TV,” says Buggy. “Here you have to talk. Everyone chats, has a good time, and leaves happy.”