I’m sitting on a shuttle, surrounded by octogenarian couples from around the country. The bus is being driven by a former employee of the government site we’re touring, spilling stories about what went on here. I sit by myself, feeling like a spy from a John le Carré novel as I scribble secrets into my notebook.

Key Takeaways

- Oak Ridge secretly produced uranium for the Little Boy bomb that hit Hiroshima, killing tens of thousands in months.

- Workers in the Secret City followed strict silence rules, many never learning what their wartime jobs actually did.

- Today Oak Ridge offers rare public access to reactors, churches and labs that bring nuclear history very close.

“Are you working on a school project?” one of the fellow visitors asks over my shoulder.

“Not exactly,” I mumble, unsure of just how much information to divulge.

A late-night internet research hole brought me to a story about Oak Ridge. The Tennessee town was a part of the Manhattan Project, the secret American operation to create the atomic bomb. I’d passed the highway exit for the area many times in my years of traveling to the Great Smoky Mountains without giving it a second thought. So, when I found out there was exactly one spot left for the last tour of the year, I booked it and made the 200-mile drive from Atlanta.

Exploring Oak Ridge’s Role in the Manhattan Project

Upon entering the town on an overcast morning, I’m met with dozens of cookie cutter mid century-style homes, draped in the famous fog that the Smoky Mountains are named for. I pass plenty of local businesses with names that include “Atomic” or “Secret City,” paying homage to the town’s unique history. After parking at the American Museum of Science and Energy, the starting point for the tour, I show my identification at the front desk and am handed a boarding pass for the bus.

American Museum of Science and Energy Exhibits

Inside the Smithsonian affiliate museum, there are identification cards from the Oak Ridge scientists, calutron machines, industrial cleanup suits, Ed Westcott photos, and interactive panels showing how the uranium isotope creates a chain nuclear reaction. But all of this is only a preview of the larger story.

How Oak Ridge Became a Secret Nuclear City

The town of Oak Ridge was built in 1942, in the midst of a race to beat Germany to be the first to create a nuclear weapon. Nuclear physicist Robert Oppenheimer assembled a team of scientists in multiple sites around the country to test different chemicals for reactions to fuel the bomb.

A few years earlier, the Army Corps of Engineers had acquired roughly 60,000 acres between Black Oak Ridge and the Clinch River, all of which were to be used for a top-secret facility. Located near Knoxville, Oak Ridge was chosen for its abundant land, low population, and easy access to other research locations in D.C., New York, and Chicago. It also had access to water from the rivers and electricity from dams recently created by the Tennessee Valley Authority.

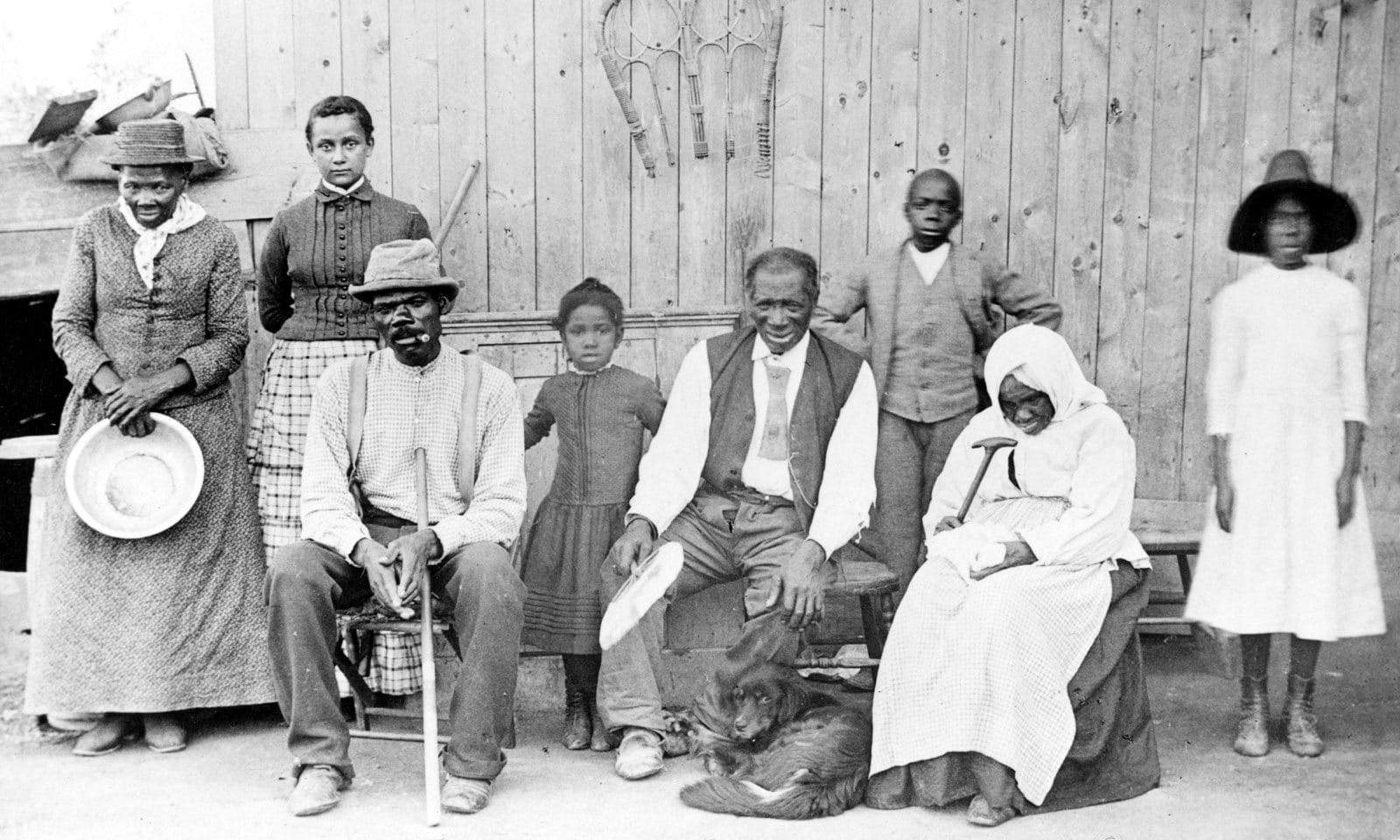

Displacement of Local Communities for the Nuclear Project

The area’s farming communities were displaced and residents were evicted with short notice. Tobacco and sorghum plants were left in the ground, waiting for a harvest that would never come.

In the years that followed, the population of the town swelled to 75,000. Seemingly overnight, Oak Ridge became the fifth-largest city in Tennessee. Some residents were high-level scientists, while others were recent high school graduates who had come from the South and beyond.

Segregation and Living Conditions in Oak Ridge

Three thousand homes were brought to town for the workers, complete with walls, floors, wiring, plumbing, and even furnishings. But not all accommodations were equal. Black workers, even those with advanced degrees, were segregated into shacks called “hutments.”

Life Inside the Secret City

Nicknamed the “Secret City,” thousands worked in Oak Ridge without knowing entirely what they were working on. Signs throughout the facility warned about the importance of remaining quiet about the work they were doing. The “Loose talk helps our enemy” message was similar to the “Loose lips sink ships” propaganda posters from the time.

Even family members couldn’t discuss their work. In fact, most of the employees at the Clinton Engineer Works, as it was known to the public, had no idea what their role was in the war effort until much later.

The Calutron Girls and Their Hidden Work

A large percentage of the employees were young women, charged with watching the meters on the machine that separated isotopes of uranium at the Y-12 Facility. Many of these “Calutron Girls” were just out of high school, and were chosen for their ability to focus on the movement of the dials rather than trying to fix a problem. Their stories are told in the book The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II by Denise Kiernan.

Within three years, the intended purpose of Oak Ridge was achieved. Teams at the facility enriched the uranium that went into “Little Boy,” the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. This one bomb killed an estimated 90,000 to 166,000 people in the four months following the explosion and forever tied the Tennessee community to the destruction of the Japanese city.

Touring Oak Ridge and Its Nuclear Legacy

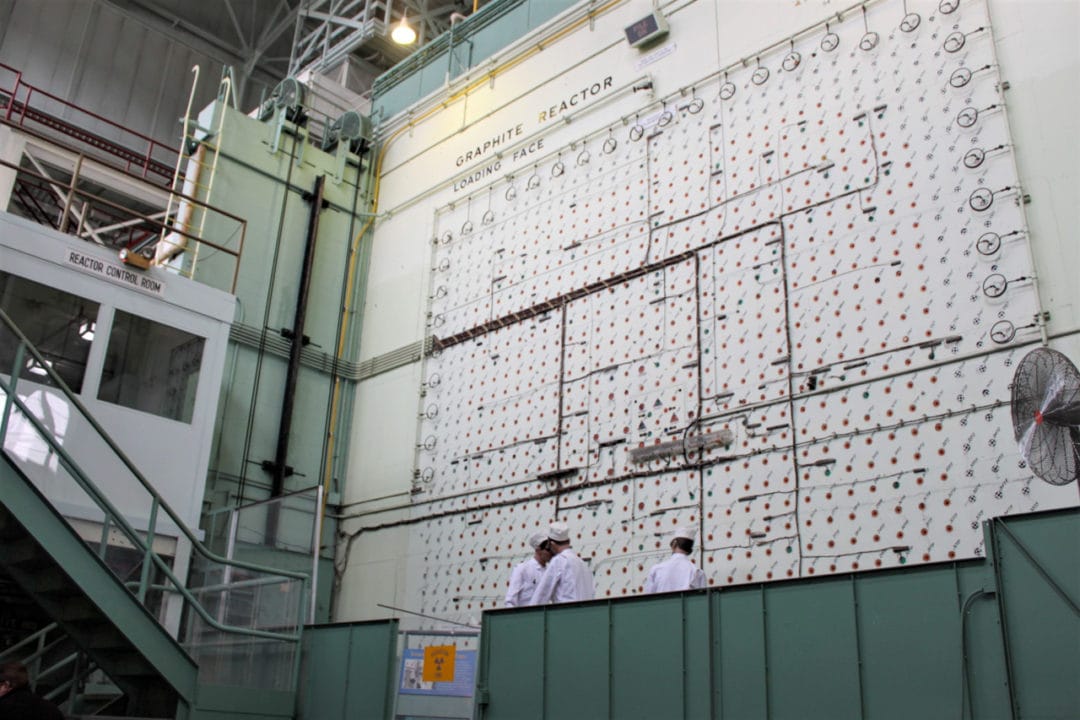

Now Oak Ridge is part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, which also has locations in New Mexico and Washington. Guided tours began in 1996, with visits to the Y-12 New Hope Center, the Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and the former K-25 site at the East Tennessee Technology Park.

The bus winds through roads that aren’t open to the public, passing through the former gatehouses that kept out civilians. Each of the buildings were constructed miles apart in case of an accident. Employees were bussed from a central location so that they couldn’t see the entire facility, similar to how we are getting around today.

Our first stop is New Bethel Baptist Church, where we briefly hop off the bus to learn about the community that was abandoned during the creation of the Oak Ridge Townsite. Pews, family photos, and graves serve as a reminder of the time before the Manhattan Project.

Inside the Y-12 National Security Complex

At the still-active Y-12 center, we watch a short film on the facility’s history and learn about the electromagnetic uranium plant. There’s a room full of historic artifacts from the Manhattan Project era, as well as the “space box” created for NASA to bring samples back from the moon.

We make a quick drive past the former site of the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant. Our guide shows us pictures of what it looks like inside the 2-million-square-foot plant used to enrich uranium using the gaseous diffusion process. Back in the day, workers would traverse the miles-long U-shaped buildings by bike. The K-25 Visitor Center provides additional information about the plant’s work.

Outside of the X-10 Graphite Reactor, groundhogs pop up from the earth but we can’t take photos of the exterior of the facility due to ongoing work nearby. I learn that this was the first plutonium refining facility and the world’s first continuously operated nuclear reactor. Mannequins show how workers carefully held long rods in place in hundreds of holes in the reactor. The clocks at the monitors remain in the position they were in when the site was decommissioned.

Before heading home, I pay my respects at the International Friendship Bell Peace Pavilion, created in 1993 for the 50th anniversary of Oak Ridge. On the massive forged bell are the dates of both Pearl Harbor and V-J Day—dates that tied two places on opposite sides of the globe together.

Oak Ridge’s Impact on Modern Science and National Security

Hiroshima wasn’t the end of Oak Ridge. Despite the consequences of the atomic bomb, the work from the Manhattan Project led to advances in power, science, and technology that have applications today. Oak Ridge National Laboratory used technology from the labs to test a NASA probe’s heat shield and made a plutonium isotope to fuel spaceships.

The Y-12 National Security Complex maintains the United States’ nuclear stockpile, works with nations to dispose and decommission nuclear weapons, and uses uranium for the U.S. Nuclear Navy.

Environmental Concerns and Cleanup Efforts

It hasn’t been without controversy, of course. In 1989, the Environmental Protection Agency named the Oak Ridge Reservation a Superfund Site due to contamination. Cases of cancer in Oak Ridge residents have also been investigated for a possible link.

While the United States’ relationship with nuclear weapons is fraught with complexity, Oak Ridge is one of the few places that offer visitors a visceral look at the era, especially compared to the limited access of similar sites in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Hanford, Washington.

“Oak Ridge has far more for the public to see than is available at any of the other sites,” says Ray Smith, a former Y-12 employee and Oak Ridge town historian.

If You Visit the Secret City

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, bus tours are currently on hold. Contact the American Museum of Science and Energy directly for the latest information. In the meantime, you can take a virtual tour of the K-25 Building.