The first time I ever set my eyes on Oatman, Arizona, I was a reporter at the Phoenix Gazette in 1984. Charlie Stoll, a miner from Oatman, had been arrested by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) on charges of assaulting one of their agents during a drug bust in the area. I drove to Oatman to interview Stoll, who was the unofficial mayor of the town—and not nearly as bad as the DEA had portrayed him.

Key Takeaways

- The Oatman Hotel becomes a centerpiece of the town’s story after surviving a major fire and hosting a famous Hollywood couple.

- Oatman’s steep mining history shows its huge early wealth, as miners pulled out over thirty six million dollars in gold.

- Wild burros freely wander the streets and remind everyone that the small desert town still belongs to them.

But the real treat was the town itself: Oatman turned out to be a relic of the past; a near-ghost town nestled in a craggy mountain range between Kingman, Arizona and Laughlin, Nevada. It’s a place I would return to again and again over the years.

The Oatman Hotel and the Gables: Historic Route 66 Hotel in Oatman, Arizona

I sit on the porch of a house that once served as a miner’s shack, looking at the moon and listening to the mournful coyotes howling in the distance. I can also hear the honky-tonk piano player at Fast Fanny’s Place, a bar in the downtown area. Wild burros drift in from the nearby mountains and sniff suspiciously at me. If I approach them, they drift off into the darkness, probably to harass another tourist for a free meal handout.

From Booming Arizona Mining Town to Near-Ghost Town

The mountains around Oatman are rich with gold, silver, and other minerals. At a time when gold was selling for $20 an ounce (today the price is between $1,400 and $1,500), miners removed more than $36 million from the mountains. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Oatman was a booming mining town with more than 10,000 residents, two banks, seven hotels, 20 bars, and a dozen other businesses.

Miners failed to deplete all the gold and mines still operate profitably in the district, although the population has fallen to less than 200.

Olive Oatman’s Tragic Story and How the Arizona Town Got its Name

The town was named after Olive Oatman, an Illinois teenager who was kidnapped by members of a Native American tribe in 1851, while she was traveling west with her family. Olive’s parents and four of her siblings died in the attack, but a brother managed to escape. Olive and her sister Mary Ann, who later passed away, were captured. Olive became a de facto member of the Mohave tribe until 1856, when she was released and reunited with her brother, her chin permanently tattooed with a tribal design.

Haunted Oatman Hotel and the Legend of Oatie the Miner’s Ghost

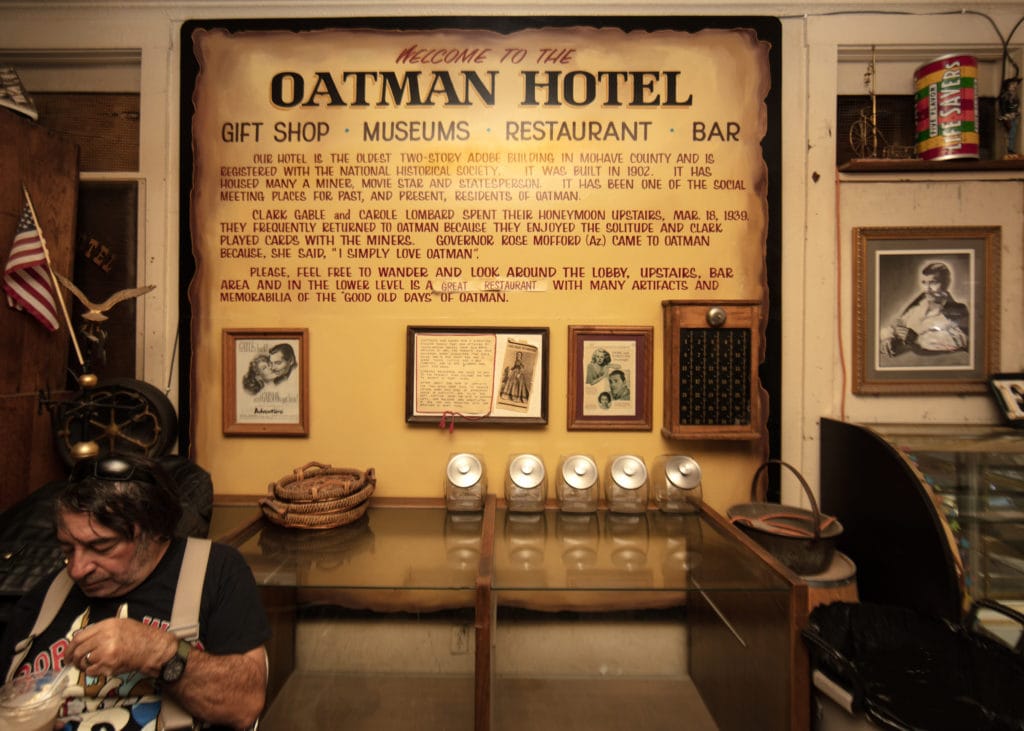

In 1921, a fire swept through Oatman, destroying many of the buildings. Miraculously it missed the Oatman Hotel which today is well-known for two reasons: It was where Clark Gable and Carole Lombard spent their wedding night after being married in nearby Kingman on March 18, 1939—and it is the home of a ghost nicknamed Oatie.

The two-story hotel is the oldest adobe structure in Mohave County. While guests can no longer stay in the historic building, the top floor has been converted into a museum. The hotel’s restaurant, bar, and the room where the Gables spent their wedding night are still open to the public. A replica of Lombard’s blue wedding dress is displayed on the bed.

I could easily imagine Gable playing poker and drinking with the miners, prospectors, and tourists who gathered in the town’s bars. An old-timer told me, “Gable wasn’t much of a poker player. He knew what he was doing, but he didn’t care much whether he won or lost. He just enjoyed the companionship of the folks who lived here. He told us it sure beat Los Angeles and having to fight off the press corps.”

Hotel guests and employees have reported spotting a spirit roaming the halls of the old building at night. The current owners claim Oatie is what remains of William Ray Flour, an Irish miner who reportedly plunged to death into a mineshaft behind the hotel during a drinking binge.

The Wild Burros of Oatman, Arizona

After a comforting sleep, I get up, take a bath, and walk out onto the porch, where I encounter a brown and white burro. I wander down to Main Street to have breakfast at Fast Fanny’s. The honky-tonk piano is still playing, although there’s no piano player present. It plays automatically, the manager tells me.

“It keeps the customers entertained and we don’t have to pay the player,” he says with a grin.

I continue up a hill to an abandoned mineshaft, where red signs warn me to keep out. While standing there, an older man approaches me. “This was once a mine that produced a lot of gold,” he says. “It was flooded and the owners shut it down, but there’s still a lot of gold ore in it—if you could figure out how to get it without drowning in the process.”

There was so much gold in the mountains around Oatman that another rush—one of the last in the desert—occurred in 1915. This brought with it another influx of prospectors, miners, saloons, and other businesses. A newspaper, the Oatman Miner, was established and the town once again prospered for several years.

During World War II, however, the federal government needed other metals for the war effort and many of the miners left the area for higher-paying jobs. Some of Oatman’s mines shut down completely while others slowed their operations. In the 1950s, Route 66 was rerouted and the new interstate bypassed Oatman completely.

Driving Old Route 66 to Oatman’s Narrow Desert Curves

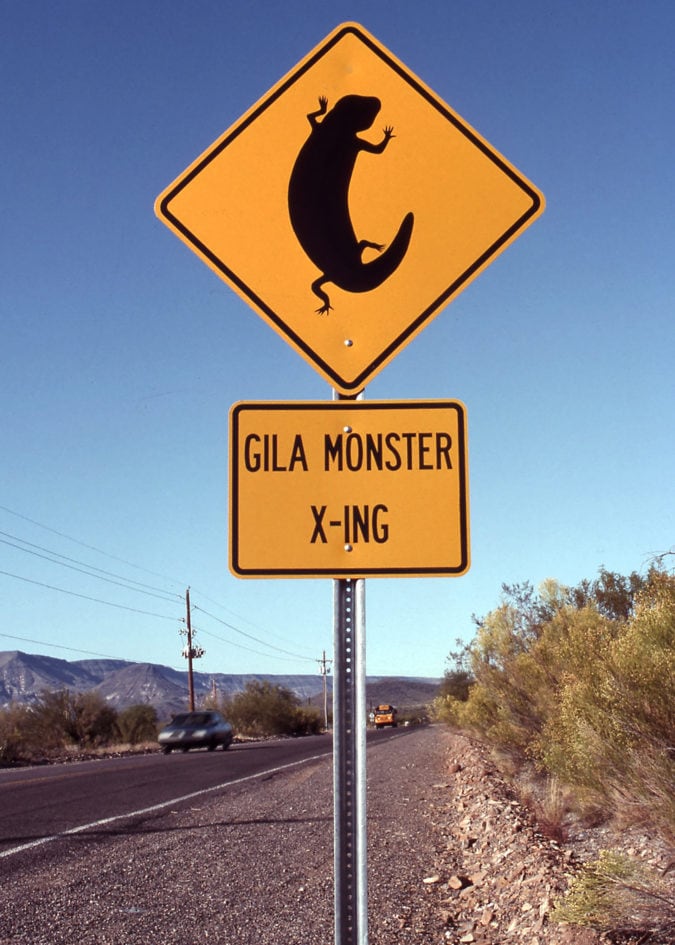

Today, the old Mother Road is a narrow, twisting road through the high desert. The road is often blocked by wild burros, coyotes, rattlesnakes, or Gila monster lizards. In 1995, the gold mines in the Black Hills came to life again when another gold discovery was made.

Old West Gunfights and Street Shows in Downtown Oatman

I’m back in the downtown area when a group of cowboys wander into the street. One of them shouts an insult to the others, and the next thing I know they are firing blanks—a regular shootout at the O.K. Corral. The cowboys and the tourists seem to enjoy it and nobody gets hurt except for a tourist who tries to mount one of the burros. The animal doesn’t appreciate his efforts and dumps him into the street while his friends howl. It’s a good reminder that friendly as they may seem, Oatman belongs to the burros. We’re merely guests in their town.