Every beer brewed at Carillon Brewing Company provides a glimpse into the lifestyles, agriculture, industry, and melting pot of cultures in a growing 19th-century Midwest town. When the settlers living in the rapidly growing frontier towns of the mid-1800s found the water from their wells undrinkable because of human contaminants seeping into the groundwater from nearby outhouses, they did the next best thing: They drank beer.

Carillon Brewing Company, located within Carillon Historical Park in Dayton, Ohio, transports visitors back to the 1850s, when ale was safer to drink than water and in high demand for quenching the thirst of the area’s hardworking Irish, English, and German immigrants. Many had brought well-honed brewing skills along with their taste for ale.

As the only licensed brewery in the U.S. owned by a museum with the ability to sell its product to the public—and the only U.S. brewery replicating the historic brewing process of the frontier—Carillon Brewing tells this story through food and drink. The brewers’ challenge is to strike the balance between historical accuracy and flavors that appeal to modern tastes.

“We can never truly replicate history,” says brewmaster Kyle Spears. “Instead, we focus on historical interpretation to invoke the flavors that would have existed historically.”

Related: 8 great craft breweries along Ohio’s 250-mile Brew Trail

Copper kettles and oak barrels

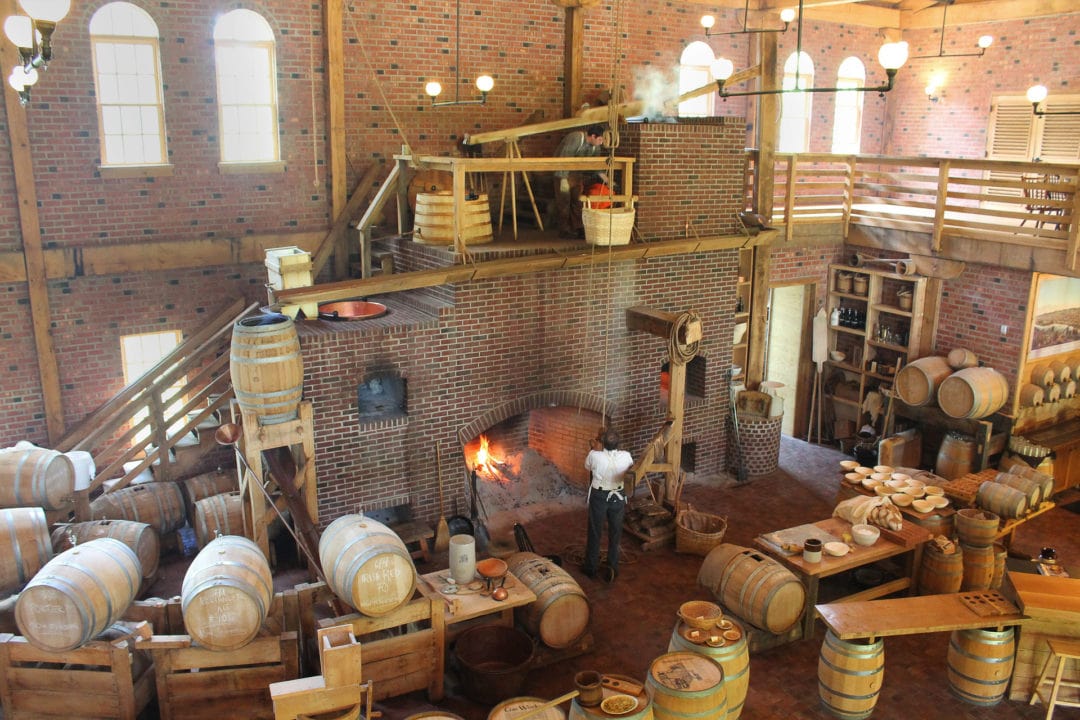

The two-story brick brewery is hard to miss as I enter the park’s campus. The words “Cash for Barley,” boldly painted on the facade, harken to a time when advertisers didn’t waste words. Just outside the entrance, a green wagon with bright red wheels sits loaded with American oak barrels. Beside it is a 6-foot stack of firewood, the only fuel to be used for historic beer production.

Once inside the heavy doors, the brick-and-wood interior surrounds me with cozy warmth. Heavenly aromas abound, including that of malted grains in a steaming copper kettle, spent-grain sourdough bread baking in a wood-fired brick oven, and a pleasant hint of smoke in the air.

I notice barrels everywhere, even suspended from the timber ceiling beams. While some support work surfaces, others are educational. As I move down the row of 12 barrels standing upright along the work area, I see each one is capped with an engraved explanation of the steps in the brewing process.

The production area hums with activity, bringing history to life before my eyes. Period-dressed brewers in button-fly pants, blousy shirts, suspenders, and well-worn work boots attend a multi-tiered, gravity-fed brewing system that operates with ropes, pulleys, and chutes (no automation allowed). Flames blaze in the oversized brick fireplace and also in the brick furnace on the brew deck 14 feet above the floor.

Tastes like home

In the hands of brewers skilled in historic ale production, the 19th-century tools of the craft become more than a dusty display of artifacts. The lidded mash tun, a copper kettle insulated with a wooden, barrel-like surround known as cooperage, is used for steeping malted grain, the all-important backbone of beer. Copper kettles known as “coppers” are used for boiling water (making the ale safer to drink than water) and wort, the sugary liquid extracted from the grain that will produce alcohol during fermentation. A long-handled wooden mash paddle is used for stirring the steeping grain. The copper wort dipper provides for ladling water and wort.

Like all the beers on the menu, the rye pale ale I choose would have been well known to brewery patrons 170 years ago. Adding locally-grown hops, squash, beets, and peppers to historic ales creates distinctive flavors that would have filled immigrants with memories from their home countries.

Taps at Carillon Brewing rotate with seasonal offerings such as Roggenbier, spruce ale, and Weizenbock. The flagship brews—including coriander ale and porter, as well as root beer and Concord wine made from regionally grown grapes—thankfully never leave the menu.

A nod to the past

Brewers painstakingly research diaries and cookbooks for long-forgotten recipes. “The coriander ale recipe was unearthed by our first head brewer, Tanya Brock, in the year of research prior to opening,” Spears says. It came from a homemaker’s guide, Receipts for the Husbandman and Housewife, published in Cincinnati in 1831.

To ensure authenticity, Spears and lead brewer Dan Lauro study mid-19th-century newspapers for ads that provide clues about beer ingredients being sold in local shops. They scrutinize canal boat manifests to check for goods being sent to Dayton.

I choose a seat in the spacious beer hall, although the outdoor beer garden is inviting. I indulge in the perfect complement for my beer: a German soft pretzel accompanied by bier cheese and mustard, served by a young woman costumed in a full, floor-length skirt topped with a homespun apron. The food menu also offers traditional European cuisine, including a wurst platter and sauerkraut balls for adventurous diners and classic burgers for those leaning toward American fare.

The concept of an interactive, historically authentic brewery was the brainchild of Brady Kress, president and CEO of Dayton History, the parent organization for Carillon Historical Park. His goal is always to immerse visitors in Dayton’s past, from the fully operational 1930s letterpress print shop to the working, old-fashioned carousel.

“I saw how people engaged with our print shop,” says Kress. “They could smell the ink and watch volunteers set type and operate the press. I wanted to create more opportunities like that to bring history to life, and the idea for the brewery followed.”

The museum also touts the genius of the city’s favorite sons, the Wright Brothers. The 1905 Wright Flyer III, the world’s first practical airplane, was presented to Carillon Park by Orville Wright himself.

“The story of beer making is not just about the process or ingredients, but of the people, politics, and culture of everyone impacted by it throughout time,” says Spears. “The brewery and our beer act as vehicles to deliver those stories to the public.”

If you go

Carillon Brewing Company is open 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. Sunday, Wednesday, and Thursday, and from 11 a.m. to 10 p.m. on Friday and Saturday.