In the late 1800s, New York City—with nearly a million people concentrated in lower Manhattan—was experiencing a horse manure crisis. The brick and cobblestone streets were choked with people, vendors, and horse-drawn streetcars, the latter of which produced 2.5 million pounds of manure every single day. It is estimated that if the horses had remained, Manhattan would have been buried under nine feet of equine excrement by 1930.

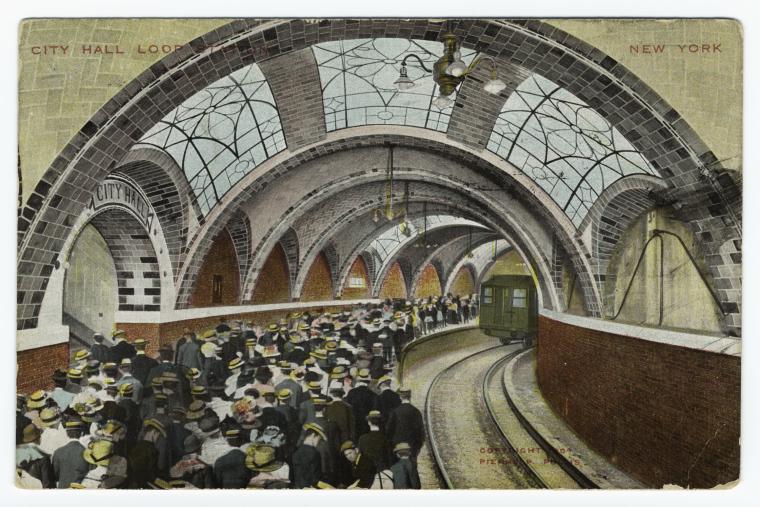

Anyone who has ever visited New York knows that, thankfully, this disgusting prophecy didn’t come true—even if it sometimes still smells as if it did—in part because of the advent of non-horse-reliant public transportation. Construction on the city’s subway system began in 1900, and on October 27, 1904, the first station opened beneath City Hall in lower Manhattan.

Today the old City Hall station—closed since 1945—is popular with urban explorers. If you want to avoid a criminal trespass charge, you can take a sanctioned tour, available only to members of the New York Transit Museum. But be warned: Tickets only go on sale three times a year and sell out quickly.

The next round of tickets goes on sale to members on April 17. It is “one of our most popular behind-the-scenes tours,” says Regina Asborno, deputy director of the New York Transit Museum.

Pneumatic tubes and a historic blizzard

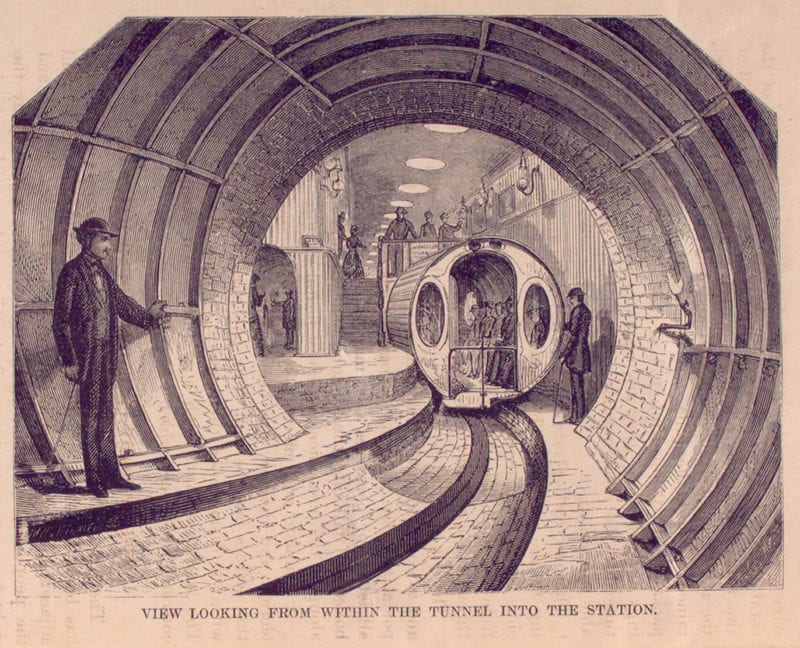

Technically, the old City Hall station is New York City’s second “first” subway station. In 1870, Alfred Ely Beach—an inventor, publisher, and lawyer—designed the city’s first underground public transportation, which he called Beach Pneumatic Transit.

While the construction of the eight-foot-in-diameter tube was obvious, its purpose was not. Beach got permission from notoriously corrupt Tammany Hall to build a pneumatic mail tube, which, he claimed, would carry letters deposited in lampposts to the nearby post office.

The tube, which took 58 days and $350,000 of Beach’s own money (about $6.2 million today) to construct, was actually conceived as the city’s first subway line. Passengers brave enough to try it out—and rich enough to afford the 25-cent fare—entered through a department store entrance, lavishly decorated with paintings, chandeliers, pianos, and fountains. One round, wooden car carried riders 312 feet under Broadway, from Warren Street to Murray Street and back again, blown by a gigantic fan.

Beach’s smooth, quiet, and comfortable prototype was a success—and proved that not only was underground transit possible, but it was popular. Beach lost his funding in the 1873 financial crisis and the tube was sealed, forgotten until 1912 when it was rediscovered by workers digging the R line. The tube and car were destroyed, but the public’s appetite for public transit was not.

The first elevated railway in New York City opened in 1868, but the blizzard of 1888 exposed flaws in the outdoor, above-ground transit system. The storm dumped nearly two feet of snow and created drifts of up to 50 feet in a unprepared city, trapping 15,000 New Yorkers on elevated trains—some for up to 24 hours.

The Sanitation Department was formed to help clear the snow, power and communication lines were buried to prevent future damage, and on March 24, 1900, the privately-owned Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) company began building the city’s second underground subway station.

The city goes ‘subway mad’

On the day it opened, 150,000 people passed through the old City Hall station, referred to as the “Jewel in the Crown” by the New York Transit Museum. By the end of the week, one million people had used the Romanesque-Revival station, which features brass fixtures, wrought iron chandeliers, three skylights, and Guastavino-tiled arches.

With Mayor George B. McClellan at the helm, the inaugural ride carried “silk-hated, frock-coated dignitaries” 9.1 miles through 28 stations—from City Hall to Grand Central Terminal, across 42nd Street to Times Square and then up Broadway to 145th Street.

“The other stations were utilitarian boxes that could not compare to City Hall’s,” writes Clifton Hood in his book 722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York.

“New York City went ‘subway mad’ over the IRT’s inauguration,” Hood writes. “For the preceding few weeks, hundreds of New Yorkers held ‘subway parties’ to celebrate the big event. Church bells, guns, sirens, and horns resounded all day long.” Spectators gathered on a viaduct to watch the first train emerge from beneath the surface in uptown Manhattan.

“The sheer exuberance of opening night proved to be too much for others,” according to Hood. “Although they bought their green IRT tickets and entered the stations like everyone else, these timid passengers were so overwhelmed by their new surroundings they did not even attempt to board a train. All they could do was stand on the platform and gawk.”

City (Beautiful) Hall

The old City Hall station was designed as part of the City Beautiful movement, by architects Heins and LaFarge. Known for their work on churches, Heins and LaFarge worked on the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, and it’s not hard to see their influence in the City Hall station’s vaulted ceilings and leaded glass skylights. “The flagship station at City Hall was an underground chapel in the round,” writes Hood.

The arches are tiled with Guastavino tiles. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Circular skylight above the mezzanine. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The leaded glass skylights are now missing a few panes of glass. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Customers purchased tickets from an elaborate oak ticket booth located on the mezzanine for five cents—the fare didn’t increase until 1948, when it doubled to ten cents. According to former New York Transit Museum educator and current tour guide Katherine Reeves, it didn’t take long for the close confines of the subway to attract crime. “The station wasn’t open fifteen minutes before someone was robbed,” she says.

The City Hall station follows a very sharp curve, necessary to help trains navigate the foundations of the City Hall Post Office and Courthouse, which was demolished in 1939, and City Hall itself. The station was built to accommodate five-car trains with doors on each end—the introduction of side doors in the 1940s exposed a cavernous, and potentially dangerous, gap between the curved platform and the train car doors.

In 1940, the city bought the IRT and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (later called the BMT), combining both lines with the city-owned Independent Subway System (IND). In 1953, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) was created to control all subway, bus, and streetcar operations; in 1968 these entities were placed under control of the state-level Metropolitan Transportation Authority, known as the MTA.

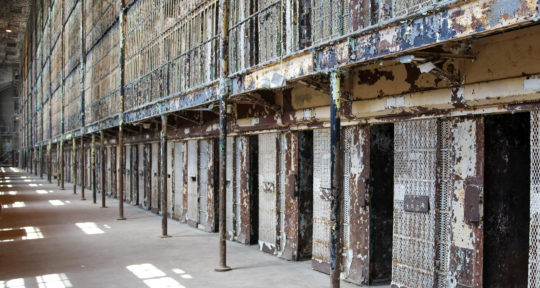

After consolidating the three subway lines, the city began to root out redundancies in their newly-unified system. The local City Hall station’s proximity to the more popular express Brooklyn Bridge station meant that ridership had been steadily declining since it opened—in its final year, only 600 passengers per day passed beneath the City Hall station’s ornate arches and it was closed for good on December 31, 1945.

Abandoned but not forgotten

Although now commonly thought of as abandoned, the old City Hall station is still considered an active part of the subway system. No. 6 trains use the track as a turnaround, screeching around the sharp curve about every eight minutes or so, 24 hours a day.

The photogenic space is not available to rent for events, weddings, or film shoots—but if you stay on the train after its last stop at Brooklyn Bridge, you can catch a glimpse of the station’s grandeur as the train loops around. However, if you want more time to take in the details (and non-blurry photos), your best bet is to take the two-hour tour.

“City Hall tours have been around since the Museum’s inception [in 1976],” Asborno says. “As part of the U.S. Bicentennial, NYCT celebrated the ingenuity of the subway system by opening up a temporary NYCT Transit Exhibit in the old Court Street Station and offering tours of the Old City Hall Station.”

Although New York didn’t have the world’s first subway system (that was London) or even the first metro in the United States (Boston beat New York City by three years), it currently has the most stations of any system in the world. There are 472 individual stations spread across all five boroughs, but it all started with the sparkling, green and white tiled jewel beneath City Hall.

“I always say that it’s not the city that built the subway,” says Reeves. “It’s the subway that built the city.”

If you go

The next round of tickets will go on sale to members of the New York Transit Museum on April 17. You can become a member of the museum here. You can also see the old City Hall station anytime by staying on the No. 6 train at the Brooklyn Bridge station with the cost of a Metrocard swipe ($2.75).