From the outside, Paisley Park looks like a telemarketing office—except when the purple lights shine at night. Inside, a hand-painted mural of Prince’s eyes greets visitors. His nameless symbol is placed as a third eye on his forehead, suggesting that I’ve crossed through a gateway into his consciousness where intuition and imagination run wild. The other lobby walls are painted sky-blue with fluffy clouds, a further expression of the unlimited distances of creative energy that once flowed from this sprawling estate.

Prince Rogers Nelson was born in 1958 and raised in Minneapolis by jazz musicians. He showed signs of being a musical prodigy at an early age, and when he was just 18 years old, he wrote, composed, produced, and played all 27 instruments on his first demo tape For You. In 1985, Prince wrote a song titled “Paisley Park” about a utopian sanctuary where smiling, colorful people discovered profound inner peace.

His dream became a reality when his quixotic complex was completed in Chanhassen, Minnesota, in 1987. This 65,000-square-foot compound is where Prince lived, recorded, and performed music for more than 30 years. The property was opened to the public as a museum shortly after his death on April 21, 2016.

Pyramids and peace

Moon and sunbeam carpeting sits underneath a starlight ceiling in the foyer, where visitors surrender their cameras and phones to protect this celestial space. Dozens of gold records line the cloud-filled walls of the atrium. The elevator is hidden behind multi-platinum discs. For a time, Prince’s ashes were on display in a customized ceramic container crafted as a scale replica of his beloved Paisley Park. His remains are now only brought into public view for special occasions.

During a guided tour of Paisley Park, our first stop is a small kitchen with diner booths. Here Prince watched Timberwolves basketball games while he ate his favorite food, pancakes. Because he was a vegetarian, Prince never served meat in his home.

The tour guide, who has long purple fingernails, shows us his office next. Here, everything is gold—except for the violet velvet couches and chairs. On an end table, I notice a pile of books about Egypt with a Bible on top. Egyptian and religious themes continue to appear throughout the tour: Glass skylights in the atrium are in the shape of pyramids and two dove bird cages sit upstairs, a biblical reference for peace.

Each room we enter is more dimly lit than the last, including the editing bay, where Prince would review his concert footage. When someone asks if the Yankee Candle sitting on the desk belonged to Prince, our guide says yes. I take note of the scent: Ocean Star. Only the lower level of Paisley Park is made public for guests, and most of the decor has remained untouched to preserve its integrity.

The Emancipation era

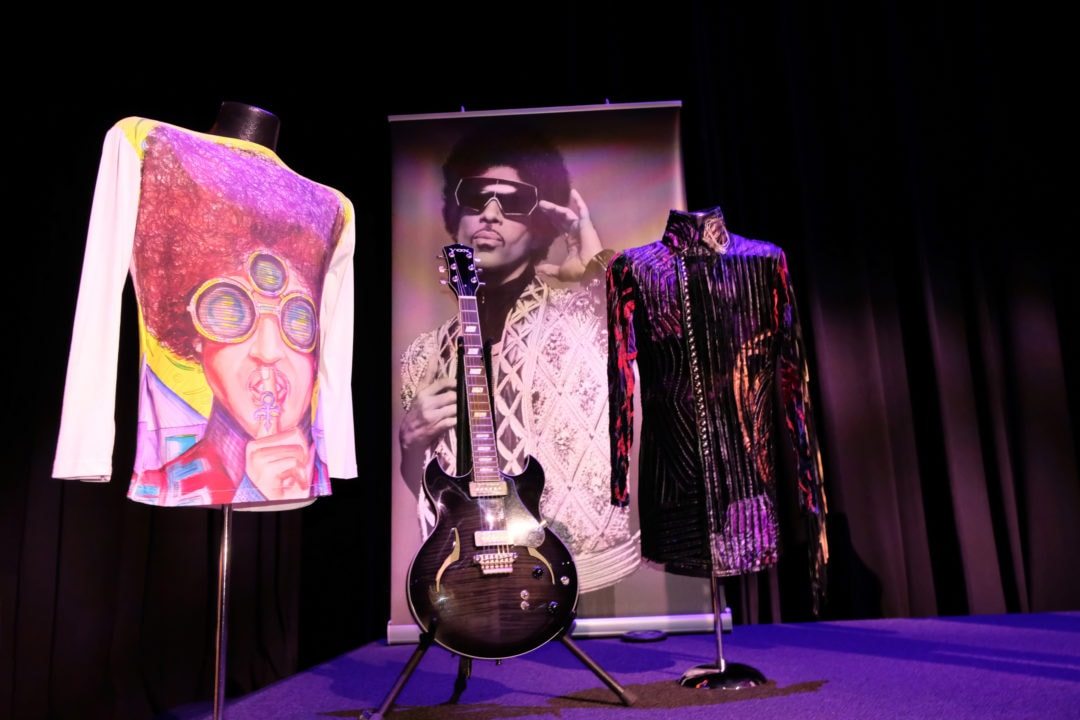

After his death, some rooms were remodeled to showcase artifacts from different periods of Prince’s life, including his dance studio. It is now home to the Purple Rain exhibition, which features a paisley suit, motorcycle, and guitars from the Oscar-winning 1984 film. The Emancipation Room has handwritten letters and memorabilia from the 1990s, when Prince temporarily changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol.

Prince’s Emancipation era was when I first became interested in his music. In high school, I was not doing much except sitting around with other teenagers, crafting “cocktails” by dropping Jolly Ranchers into bottles of Zima. However, in 1997, I worked as a ticket usher for Prince’s Jam of the Year Tour. The concert crowd was diverse and looked nothing like the hallways at my school. Boys who wore makeup, belly shirts, and platform shoes floated down to me and showed me white paper stubs that read “The Artist,” and I helped them find their seats.

When the show began, a guitar lowered from rafters, descending like a divine oracle into the hands of a prophet. Behind Prince, an organ solo ignited the stage like a stick of dynamite. He appeared to be possessed by James Brown when he sunk to the floor in a jazz split, popping back up to the microphone to sing his rendition of “Talkin’ Loud and Sayin’ Nothing.” Prince looked like a high-heeled, stringed marionette being maneuvered from the holy ghosts of rhythm and blues. When he danced on the top of his piano—or sat in front of the keys—he pulled me in deeper and sealed my fate as a fan of his forever.

Explicit lyrics

We travel through various lounges before entering his recording studios. The Galaxy Room—illuminated with black lights, walls plastered with glow-in-the-dark constellations—reminds me of my ’90s teenage bedroom. We walk through this neon universe and enter Studio B, where Prince recorded Emancipation and other albums.

Prince was a champion ping-pong player in his free time, and his table is folded in the corner of this analog studio. We’re offered a chance to take a souvenir photo in front of his custom plum-colored Yamaha piano, and everyone on my tour has dressed accordingly. I’m wearing a paisley mask I bought from a kiosk across from the Paisley Park flagship store at the nearby Mall of America.

In Studio A, our host plays a track from Prince’s vault of music that he never released. In the song, called “Ruff Enuff,” MonoNeon plays the bass and the vocals sound robotic. The song is about sex and the complicated dynamics of physical passion, with the type of lyrics that have long been a point of controversy for Prince. “Darling Nikki,” his 1984 song about masturbation, was the catalyst for the Parental Advisory labels added to albums with “explicit lyrics.”

Some critics felt that Prince’s music was in stark contrast to his faith. As a devoted Jehovah’s Witness, he regularly attended local services and was even reported proselytizing door-to-door in Chanhassen. In concert, however, Prince was an illusionist. Like the Houdini of funk music, he would emerge from a cloud of smoke, and then disappear. Seconds later, he would reappear in a fog somewhere else on stage, each time wearing a different outfit: a gold sequin suit, then a red one, then a white one with a matching top hat and cane. His stage lights changed colors to match his ensembles.

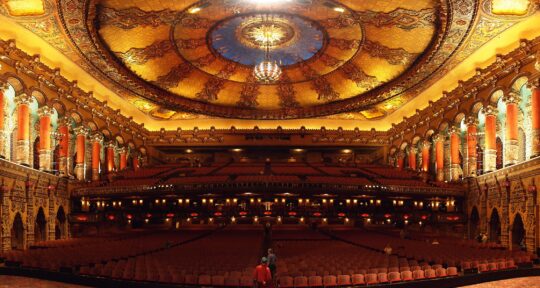

He made us all

The Sound Stage is where Prince practiced for his live performances. More of his iconic looks—most of which were custom made on-site for his 22-and-a-half-inch waist—are on display here. Projected onto the stage is his legendary 2007 Super Bowl half-time show. During his “Purple Rain” performance, he made a Miami tropical rainstorm seem like a special effect he had intentionally created. The Sound Stage mimics a rainstorm by shining thousands of tiny light beams around the darkened room. These radiant droplets spin around me while my ears are filled with the sound of The Artist singing about a purple-skied apocalypse and letting your faith in God guide you through.

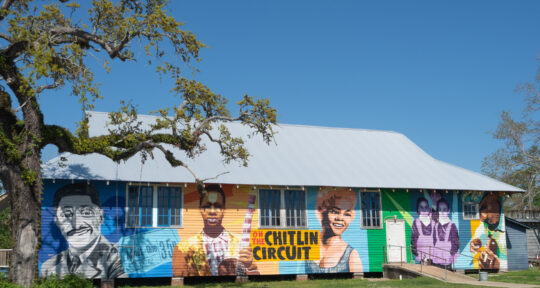

The tour ends in the NPG Music Club, where Prince threw parties for the surrounding community. He was revered internationally while remaining a beloved and engaged member of his Minnesota neighborhood. I ask the gift shop security guard about the paradox of a superstar living in a Minneapolis suburb. He tells me that Prince was known for riding his bike to the strip mall across the street to run errands.

While we talk, the 1980 music video for “Dirty Mind” plays on the giant flat-screen behind us. Prince bounces around in my favorite look of his: a trench coat, bikini bottoms, and a cowboy neckerchief. I try, but I cannot picture this endlessly mysterious character pedaling across the highway to shop at Target, just like one of us.