On my first visit to Quesnel Forks in 1973, I found the British Columbia ghost town to be as inhospitable as it must have been to gold miners who flocked to the area in the late 1800s. A wary coyote trailed me along a twisting dirt track strewn with potholes. One rear wheel of my car scrambled for a foothold along the road’s edge as I retained a death-grip on the dashboard. I stumbled into an overgrown graveyard and the lair of what seemed like a billion mosquitoes. A skittish, ever-observant silver fox family watched as I tripped through the weeds, tumbling into potholes.

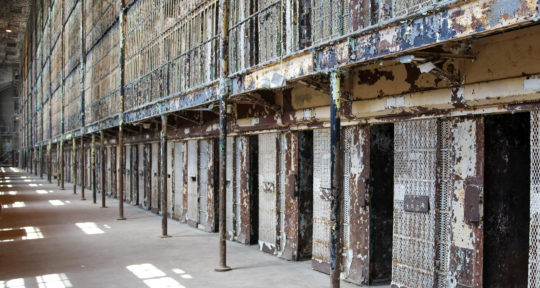

Nearby, the Quesnel River was actively undercutting the shale bank, tumbling abandoned cabins into the fast-moving, swirling waters. Waist-high weeds, wildflowers, and vines twisted around fallen logs. Most of the cabins had long ago succumbed to gravity, and only seven remained standing. I moved carefully, mindful of the dangers presented by cascading walls and attics, the buildings slowly being reclaimed by nature. Inside several cabins the floorboards had been torn up and I realized that the potholes had been created by treasure hunters.

I attempted panning for gold and nearly froze both my feet and hands—the 2,000 miners who had once trudged these same banks must have been a hardy bunch.

Quesnel Forks was once a major supply center for the Cariboo Gold Rush, but in 1866, the newly built Cariboo Wagon Road bypassed the town and most miners fled 2.5 hours north to Barkerville. By the 1870s, there were only about 100 people—mostly Chinese immigrants—left in Quesnel Forks and by 1940, only 50 hardy souls remained. The last Chinese resident, Wong Kuey Kim, died from exposure as he trekked for supplies in the winter of 1954.

Restoring a ghost town

When I return to Quesnel Forks 45 years later, a silver fox glares balefully while my 20-foot motorhome crunches downhill along a narrow road. I’m not gripping the dash on this trip but the area is still swarming with mosquitoes—some things don’t change.

What has changed is thanks to the combined efforts of the Friends of Barkerville Historical Society and the Likely Cemetery Society. Over the years, hard-working crews of volunteers have labored to partially restore this ghost town log by log. In 1987, researchers lived in the restored caretaker’s cabin and unearthed posters, death notices, and community records.

They located plans detailing the original town’s layout, which revealed that it had once been a surprisingly large pioneer outpost with 20 streets and a general store, a boarding house, a firehall, a pharmacy, and a watchmaker. Several saloons prospered and a doctor tended to the ailments of the often-transient residents.

A collapsed cabin. | Photo: Norma Watt The Quesnel Forks cemetery. | Photo: Norma Watt

By 1995, the volunteers had burrowed through years of history and in 2009, government grants enabled the restoration visible today. “The government was a lot more generous then,” says Howard Fenton, the organizing force behind the Likely Cemetery Society. “We had enough money to hire log building restoration experts.”

Along with his wife Elaine, Fenton continues to cut the grass in several remote cemetery locales. “Sadly, the government isn’t forthcoming with more money so the townsite hasn’t seen much progress [recently],” he says.

Life and death

The Quesnel Forks cemetery has been lovingly restored, its headstones telling the stories of segregation and tragedies suffered by the residents. The Chinese miners were buried in a separate area, yet without their contributions this town likely would not have prospered. “This was once the third largest Chinese settlement north of San Francisco,” Fenton says.

Reading the posted death notices is not for the faint of heart: “Death from smallpox,” “Death from mining accident,” “Buried in landslide.” Countless unidentified people drowned, died by suicide, or were killed by animal attacks. Several murder victims are buried here, often alongside their killers. Elaborate fenced-in family plots illustrate the harshness of life through death dates. Mothers and infants often died together, heartache and violence in the same time warp.

Miners hauled their tubs, wood stoves, and cast-iron heaters into town via pack mule, but my motorhome is parked at a level riverside campsite, complete with a fire pit and a table. I swat and slap my way back through the mosquitoes and the constant roar of the river soothes me to sleep at night—the same waters that once swirled fine gold into the river’s rocky nooks.