At age seventeen, I sat alone in my car, parked on the shoulder of a winding country road on the North Carolina-South Carolina border, and clicked send on an email with a closing sentence that read, “I’m gay.” Unsure of what to do next, I wept. Then I drove around until the tears stopped and the fear subsisted—if only momentarily.

At age nineteen, my girlfriend took me home to Ohio to meet her family. On a hike in the central part of the state, we were reticent to touch one another in any way, unsure if the next person to round the trail bend would meet us with anger or disgust. Once back in the car, I slipped my hand into hers, the first time I felt secure all day.

At age twenty-one, I drove across the country from North Carolina to Colorado with my best friend in an effort to move my life from my college town to my parents’ home after graduation. We stopped in Asheville, Nashville, Birmingham, New Orleans, Austin, and Lubbock en route to my new life. Aware of my anxieties about my visible queerness in unfamiliar places, my friend went out of his way to navigate us to a gay bar where we lip synched with a drag queen who performed Rihanna’s “Shut Up and Drive.”

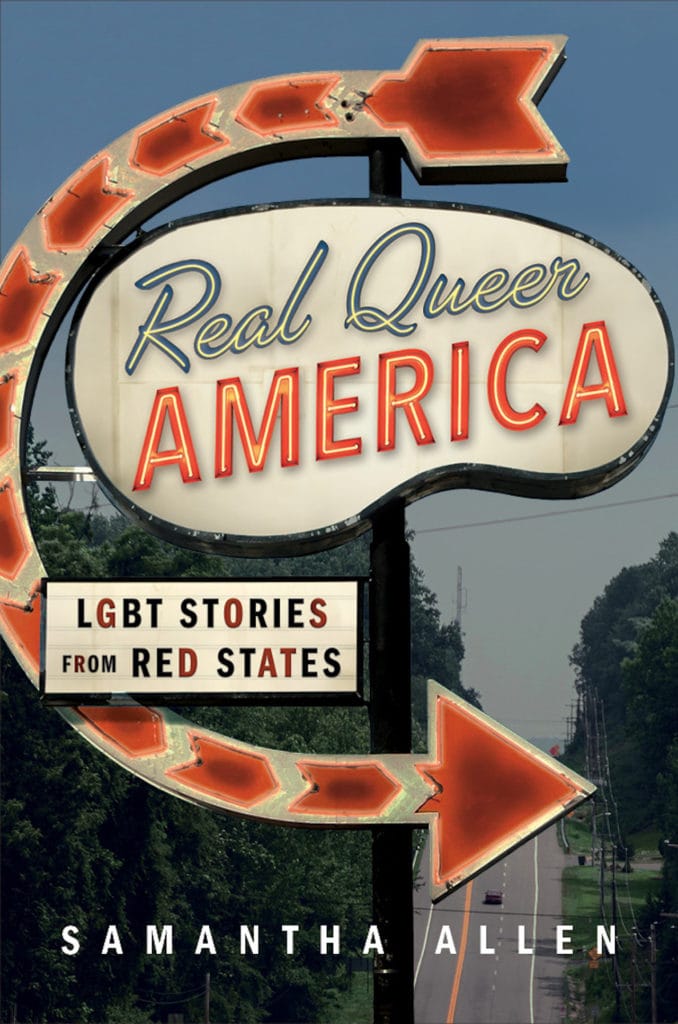

For much of my life, I longed for a book to guide me in my journeys—both physical and emotional—of coming to terms with and coming out as a queer person. Luckily, LGBTQ travelers now have the ability to find such affirmations and explorations in Samantha Allen’s Real Queer America: LGBT Stories from Red States, which was released on March 9.

Vehicles of exploration

In the summer of 2017, Allen—a GLAAD Media award-winning journalist—took a road trip across what is often termed “Middle America” in an effort to highlight thriving and active LGBTQ communities fighting for change all over the country.

Real Queer America takes readers along on her journey through Utah, Texas, Indiana, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Georgia, into enclaves that boast robust LGBTQ communities, but are not often states that come to mind when listing LGBTQ hubs.

Allen describes the book as a travelogue-slash-memoir—a narrative in which about sixty percent of the sites visited were of personal importance to her, and the rest were places she had never been before.

Allen holds a Ph.D. in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from Emory University, and woven in with LGBTQ histories, stories of queer communities, and travel musings is Allen’s personal history of coming out as transgender. Allen was closeted as an undergraduate student in Utah, came out of the closet as a graduate student in Georgia, found her LGBTQ community in Tennessee, and met her wife, Corey, in Indiana.

Allen has driven back and forth across the country at least six times, and no matter where she travels in the United States, the comfort and safety of being in a car has remained a constant.

“Cars became a really important space for me,” she says. “Living in Provo, Utah as a closeted Mormon college student, my car was really the only place I could express myself, feel like I had alone time, or [experience] privacy. So cars became an important vehicle—pun intended—for me to explore my gender identity. I, since then, have always associated being in a car with freedom—personal, individual freedom.”

Between the coasts

The idea for the Middle America road trip came as a result of the anger, frustration, and disappointment Allen saw directed toward people living in the middle of the country or in the South by folks on either coast following the 2016 election.

“I think there’s still a tendency to perceive LGBTQ folks as primarily a coastal phenomenon,” says Allen. “Even as cities—small and mid-size all across America—sprout up as LGBT hubs, we still see it as something that exists primarily in New York and San Francisco, and that is not the case.”

For similar reasons, Allen recently left her role as a senior culture reporter at The Daily Beast to pursue freelance writing full-time.

“Because national reporters are largely concentrated in New York and D.C., that has an impact on the way that our country gets represented to us. And those problems get especially acute with the representation of LGBT folks,” says Allen. “The representation of LGBT life that I see in the media is still dominantly coastal narratives, and when we do see reporting on LGBT life in other parts of the country it’s about terrible laws that were passed or things that state legislatures said about LGBT folks. I wasn’t seeing a lot about the day-to-day lived challenges and joys of LGBT communities across America.”

“We need to stop flying over these states and we need to start driving to and through them.”

In Real Queer America, Allen sought to bring attention to this missing narrative of the daily lives of LGBTQ individuals in lesser represented states. She wanted to highlight the positives of these communities, but didn’t want to sugarcoat their realities.

“The folks I talked to in the Rio Grande Valley talked about not being comfortable being out at work or being harassed on the street,” she said. “And yet, they were also just so friendly, upbeat, inviting, welcoming, and optimistic about being able to change the culture of this place.”

Allen decided to drive across the country because road trips inherently push back against the idea that any state in America is a “flyover state.”

“There’s something about being in a car. You have to fill it up, you have to go to the gas station, you have to see what kind of people are there. You have the freedom to just kind of drive around wherever and explore,” she says. “We need to stop flying over these states and we need to start driving to and through them.”

The joy of discovery

Allen doesn’t want fear or injustice to prevent LGBTQ individuals from traveling. But, she does want them to stay vigilant and be aware of their surroundings. As is the case within queer communities, there is power in unity and there is safety in numbers.

“My number one piece of advice for LGBTQ travelers is to take a friend. I totally understand safety concerns. I have them myself,” she says. “There’s no magic formula for where I feel comfortable or not. But taking a friend helps immensely.”

Throughout her trip, Allen made friends across the country who acted as her community guides, mentors, and queer compatriots—people like Jess Herbst, the first openly transgender mayor in Texas, and Temica Morton, the organizer of Jackson, Mississippi’s first pride parade. Ahead of visiting each state, Allen set up meetings, coffee dates, and interviews with LGBTQ residents. During the visits, she also allowed herself flexibility in the schedule for the opportunity to stumble upon something unplanned—or, as she calls it, “the joy of discovery.”

In Texas, Allen met new interviewees while participating in protests against the bathroom bill at the State Capitol. In Indiana, she was pleasantly surprised to find that the Kinsey Institute—the Indiana University institute in which she and her wife met—was unlocked and accessible in the middle of the summer.

Some of the unexpected treasures Allen found in her journey included Eureka Springs, Arkansas and the Rio Grande Valley in Texas—both places she likely wouldn’t have gone to on her own, but places she found because of recommendations from folks within the community. For LGBTQ travelers, word-of-mouth, in-town connections, and guides like Real Queer America are enormous assets, particularly in unfamiliar places. Allen calls this “queer world-making.”

From the time I got my driver’s license in suburban North Carolina, the hours I spent behind the steering wheel felt like the only moments in which I was in control of a seemingly unstable world. All around me, I heard homophobic slurs in the school hallways, witnessed the passage of restrictive legislation, and read stories about hate-driven attacks. I longed for a community that would allow me to meet people like me and to make my state a better place than I’d found it when I first arrived as a closeted pre-teen.

Appropriately, I pored over Real Queer America while sitting in the car in Ohio, waiting to pick my girlfriend up from a doctor’s appointment, in the queer world that I’ve made for myself—with the help and guidance of LGBTQ folks who have carved out and made this space available and accessible to me.

“The number one thing I hope the book does is inspire people to take trips of their own,” Allen says. “There’s just an almost infinite bounty of queer riches in the country to explore, and I just want people to go find their own.”